I’m reminded of a quote by Jacqueline Rose, writing about Marilyn Monroe in her book Women in Dark Times: “I do not find it helpful to present her—or indeed any woman—as either on top of or succumb- ing to her demons, as though her only options were victory or defeat (a military vocabulary which could not be further from her own).” The song is not a celebration of victory so much as it is a celebration of freedom, a chasmic difference that you can only truly understand once you’ve had to make a choice between the two.

“Daddy I’m Fine” is, of course, a song about fathers, but as with all Sinéad songs, I can’t help but think of my mother when I listen to it. And I can’t think of my mother without thinking of her mother— another woman, like all women in my maternal lineage, whose daughter left her in search of a different life.

My granny was a prototypical Irish Catholic: tough, blunt, honest, seeming to me, at the time, to need no comfort and want no frivolity. I wonder, often, what she would think of the type of woman I grew into—emotional, expressive to a fault, thin-skinned, definitionally frivolous. I sensed her disapproval of me even when I was a teenager; when I wore ripped jeans, when I wouldn’t do the dishes. I loved her, and I know for certain that she loved me intensely, but it often felt like a ritual kind of love, instinctual, rather than a love born of anything we actually had in common. I didn’t think that she understood me, and I don’t think I tried very hard to understand her.

Years after my granny died, though, my mother mentioned offhandedly in conversation that she had denied my grandfather’s marriage proposal three times before finally accepting, even though marriage to a good man, a man that she loved desperately until the day she died, was just about all that a woman could be expected to aspire to in the 1950s. I felt like the air had been knocked out of me, which is how I still feel now whenever I think about her—how little I knew of her, how much there was to understand. I realized with the shame of a child that I’d had it all wrong.

She, too, had an instinctive resistance to the life that had been set out for her; perhaps she, too, had a deep kind of hunger for a different one. And I realized that it didn’t mean anything that my life wouldn’t make sense to my granny; her life probably didn’t make sense to her granny, and that made the two of us infinitely more alike than any minor difference we had about how often I prayed the rosary. Our differences, in fact, are precisely the thing that bring me closest to under- standing her. I’m sure she felt different all the time.

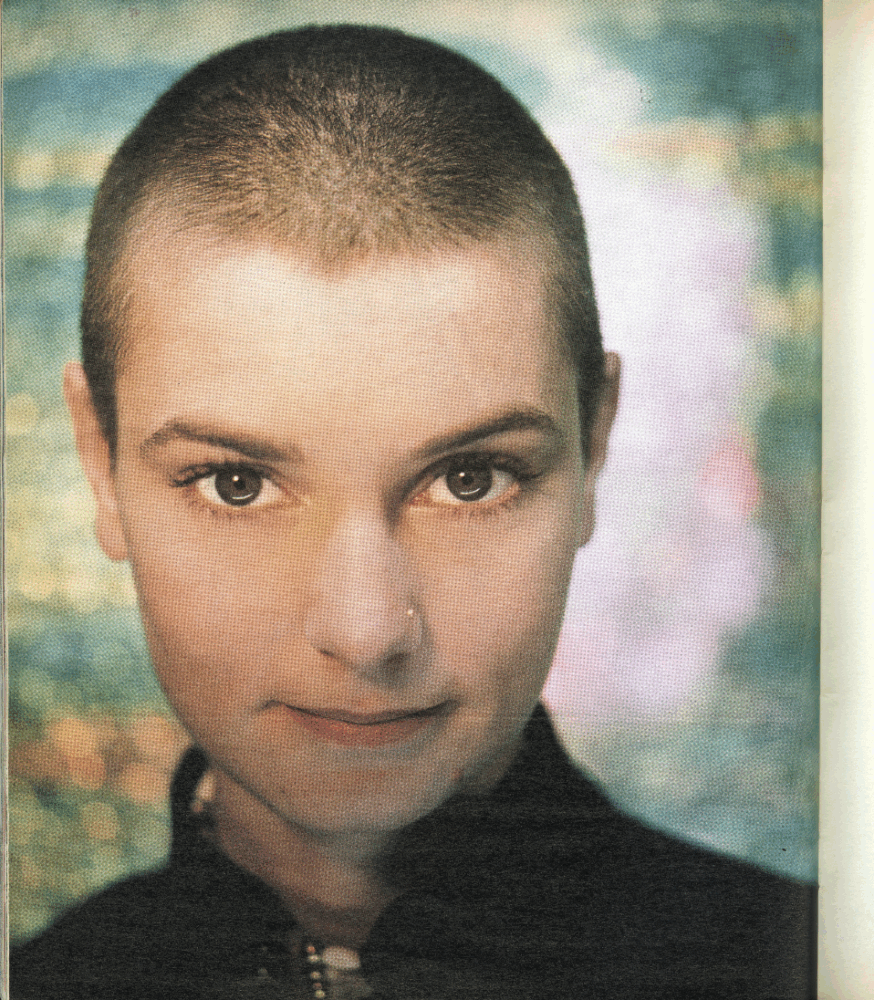

This is the core of the connection I feel to Sinéad: it’s not about technical similarities, biographies, perceptions of self—all that is subject to change, anyway. Rather, she serves as a reminder to me that some lives, even when vastly different in their particularities, have similar shapes, and that certain kinds of women have been carving their lives into inconvenient shapes for as long as anyone can remember—that our challenges and ambitions and desires may not be identical, but that they often have a symmetry, a pattern, a rhyme. The great similarity between us is not found in material details but in a larger arc of our lives, one that bends toward or against the shape we appear to be born into.

My grandmother, my mother, me; a legacy of leaving, of searching for something different than what we were promised or owed, of calling our fathers and assuring them that we’re going to be fine.