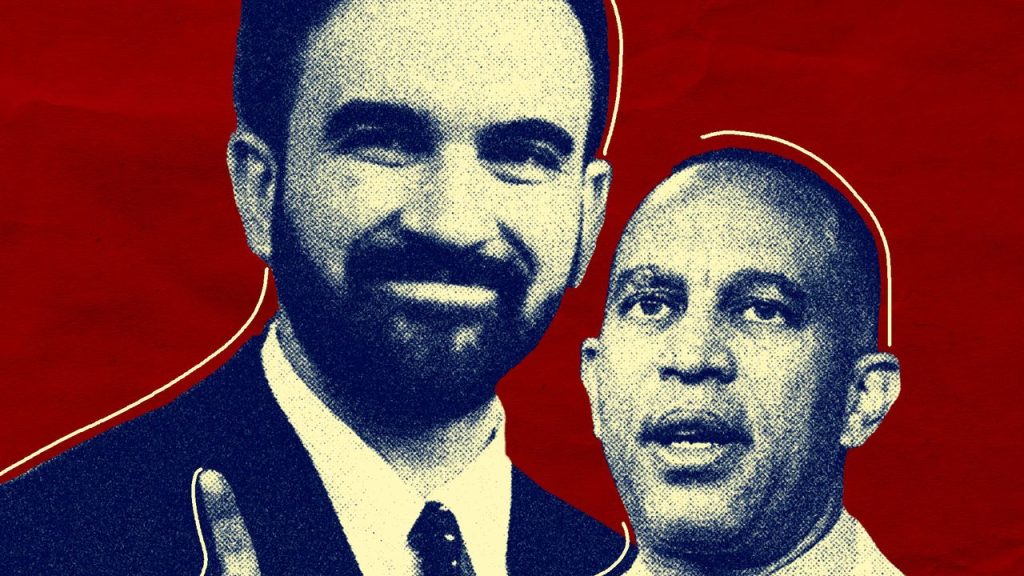

The meeting itself was important. On July 18, Zohran Mamdani, the freshly minted antiestablishment winner of the New York City Democratic mayoral primary, traveled to Brooklyn to sit down, for the first time, with Hakeem Jeffries, the Democratic minority leader of the House and one of the most powerful people in New York’s political establishment. The two men covered plenty of complicated ground in one hour, including Mamdani’s proposals to lower the cost of living and Jeffries’s determination to win back a majority in the 2026 midterms.

Yet nearly as significant as what the two men said while talking face-to-face was the message Mamdani had sent the night before, on TV. During an interview on Inside City Hall, the city’s highest-profile political news show, Mamdani said he would now “discourage” use of the phrase “globalize the intifada,” distancing himself further than he ever has from the slogan used by some opponents of Israel’s war in Gaza. Mamdani had never encouraged its use, and acknowledged that it was offensive to some, but he had not denounced it, either. “That was a sophisticated move, to go on NY1 with Errol [Louis] the night before meeting with Hakeem, and to start lowering the heat,” one House Democratic insider tells me.

In the month since his surprising and decisive win over former governor Andrew Cuomo, Mamdani has been making the rounds of Democratic elected officials, in both New York and Washington, seeking to “build a coalition,” as an adviser to Mamdani describes the outreach. In some places he’s been eagerly received, including a gathering of roughly 30 House progressives hosted by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. In other corners, the mood has been chillier: Jeffries, as well as Chuck Schumer, the Senate minority leader, and Kathy Hochul, New York’s governor, have still not endorsed Mamdani for mayor. “He’s a very likable guy,” says Jay Jacobs, the New York State Democratic Party chairman and a former close ally of Cuomo’s, who recently talked with Mamdani for the first time. “The substance is where he’s got problems. Not just the policy proposals, but the language he uses on the Middle East conflict. And the mayor’s race has national ramifications—the Republicans have already weaponized his primary win to try to paint moderate Democrats in competitive districts as being aligned with Mamdani.”

Part of the tension is parochial. Mamdani’s win fueled speculation that Democratic incumbents, possibly including Jeffries, might face primary challenges from the left next year. André Richardson, one of Jeffries’s advisers, fired back hard to CNN: “If Team Gentrification wants a primary fight, our response will be forceful and unrelenting.” Grace Mausser, a cochair of the city chapter of Democratic Socialists of America, a key part of Mamdani’s primary campaign infrastructure, tells me that DSA has no plans to challenge incumbents, including Jeffries—though she points out that Mamdani won by a large margin in the congressman’s district. “I think that probably is a little scary to him,” Mausser says. “It indicates that he may need to compromise, to adjust tactics a little bit.”

Mamdani has shown no sign of trying to lead a wider leftist insurgency. Instead, he’s opted to have conversations with the entrenched players. The approach makes sense in two ways. Enlisting institutional support—from labor unions as well as other politicians—would help Mamdani get past Cuomo, Mayor Eric Adams, and Republican Curtis Sliwa in November’s general election. But as he makes the rounds of skeptical business groups and mainstream Democrats, Mamdani is also looking toward next year and the backing he would need to function successfully as mayor. Jeffrey Lerner, Mamdani’s campaign spokesman, says the outreach is going well, as people who have only heard about Mamdani get to know him in person. “Zohran knows it’s going to take partnership to accomplish his agenda,” Lerner tells me. “And his view is that even if you disagree with him on 60%, he’s going to want to work with you on the parts where you agree. Particularly as we get to dealing with Trump and resisting authoritarianism. Senator Schumer, Congressman Jeffries, and Governor Hochul are all on the front lines, and that is an area where Zohran believes they need to be partners.”

Mamdani, in the short term, should be happy that the entire establishment hasn’t rushed to embrace him. Because in widening his circle, Mamdani risks alienating the younger, passionate base that powered his primary win, who could see him as a sellout, dulling his outsider, agent-of-change appeal. Mausser, the DSA cochair, says the party is realistic. “Of course he’ll need to make compromises. That’s part of wielding power. He is not going to bring about a socialist utopia in New York City,” she says. “My hope is that, now that he is very much a power player, establishment Democrats have to talk to him and adopt at least a little bit of his attitude, putting forward a positive vision and then fighting for it. Chuck Schumer’s big resistance against Trump’s budget bill was renaming the bill.”