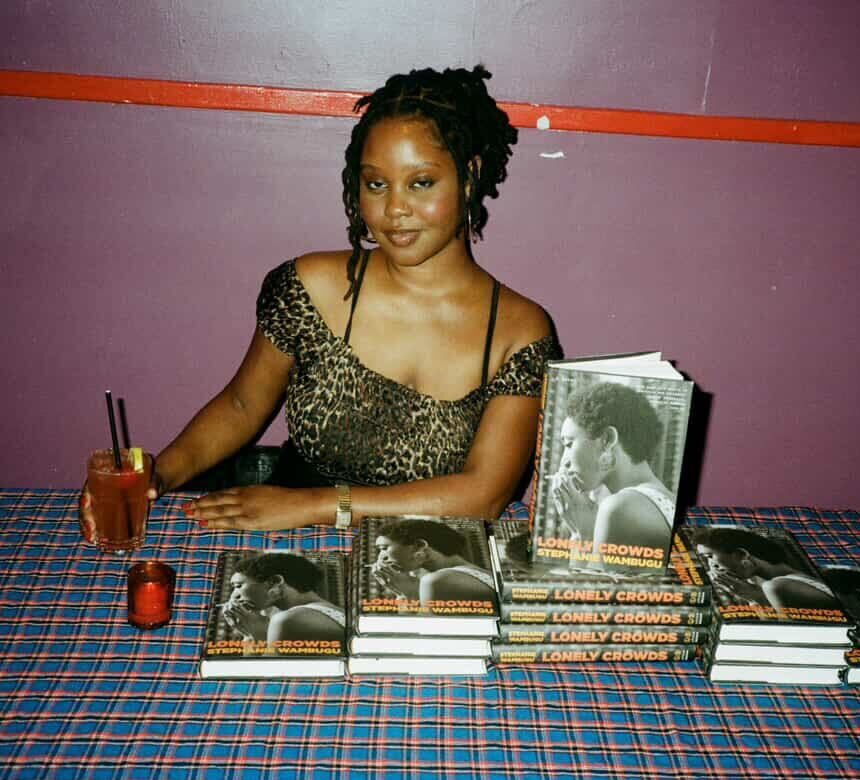

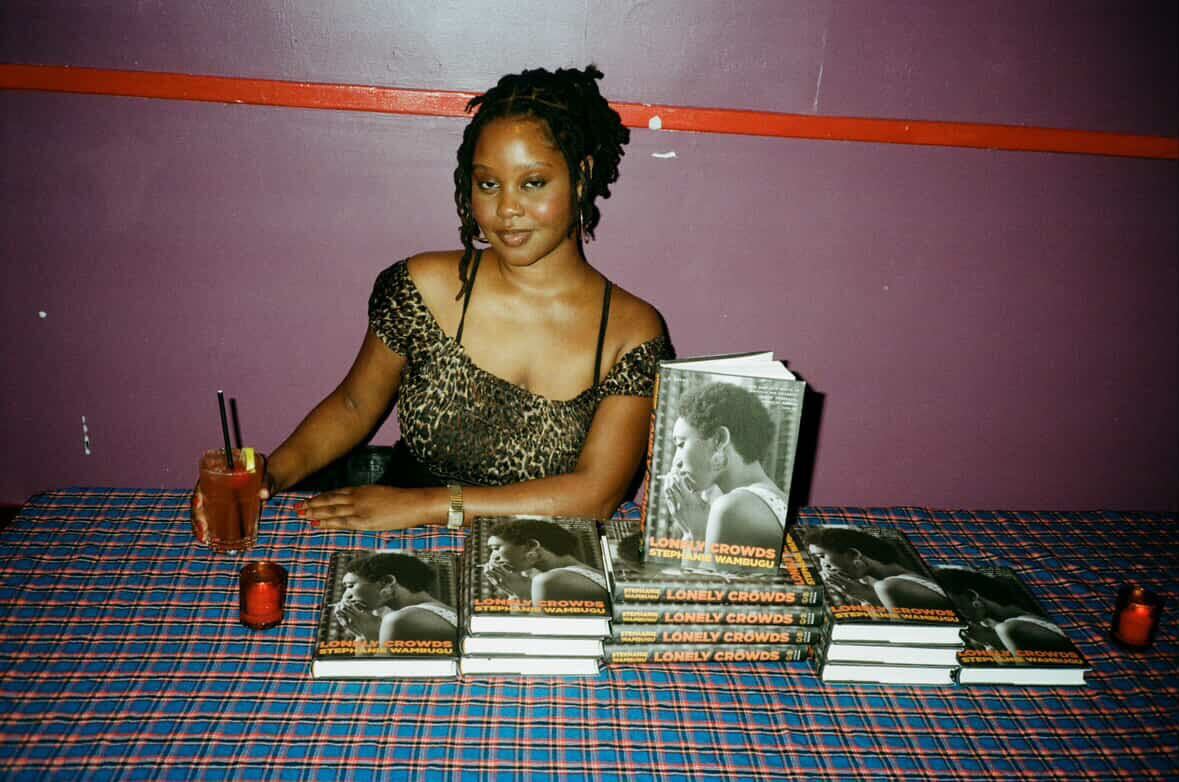

Photo courtesy of Stephanie Wambugu.

Ruth, the novel’s narrator, is the kind of person things happen to. Maria, her enigmatic foil, makes things happen. The two meet as little girls in a grocery store in Providence, where Ruth has been sent on an errand by her parents, recent immigrants from Kenya, and Maria shops with her schizophrenic aunt, her only caretaker after her mother’s suicide. Lonely Crowds follows the girls as they become women, struggling to navigate the economic realities and shifting tides of a newly identity-centric New York art scene. Kept afloat by their own convictions (and their semi-transactional arrangements with wealthy lovers), they are rewarded for their hustling—Ruth through institutional support, and Maria through the It Girl status bestowed upon her by zeitgeisty critics.

Just before the release of Lonely Crowds, I met up with Wambugu at the Elizabeth Street Garden, where she answered my questions with the same precision and wisdom one finds in her narrative voice. Wambugu, like her narrator, is a young woman artist born in Kenya and raised in Providence, Rhode Island, so I was curious to hear more about the process of crafting this narrative (while wanting to steer clear of the great autofiction debate). While chatting in a shady corner of the Garden, we unpacked her characters’ Kafkaesque breakdowns, the literary canon of toxic female friendship, and the importance of having a religious education to rebel against.

———

JULIETTE JEFFERS: So in your debut novel, Lonely Crowds, shares certain autobiographical details with you. However, from what I understand, the novel is entirely a work of fiction. From a craft perspective, how did you approach writing this narrator that shares these key life details with you, while also establishing a distance between yourself and the narrator?

STEPHANIE WAMBUGU: One of the decisions I made very early on to achieve that and to create some distance and not be conflated with my narrator was setting the book in the ’80s and ’90s before I was born. That really freed me up to not feel like I was doing such an autofictional project. It’s autobiographical in some ways, as you say, in that the character is Kenyan and has parents from another country and grew up in New England. But other than that, it really is not adherent to my personal life. I thought it was very important to create some distance and to create a little bit of anonymity for myself by setting it in a time period that’s not contemporary.

JEFFERS: The novel is very subtly set in the ’90s. You don’t really get a sense of exactly what year you’re in. You just know people are only calling each other on the phone, and Adderall is just starting to be a thing in the culture.

WAMBUGU: hoped it would be timeless because, as you say, I could have written a roman à clef that’s set in 2019 with the exact same cast of characters just transported to the contemporary art world. But I also didn’t want to have to be allegiant to our technology and have to talk about the internet and that kind of thing. But you’re right that it could have been set 20 years prior or 20 years after. Grifting is timeless.

JEFFERS: Grifting is forever. The main characters of your novel, Ruth and Maria, are both women artists, and they’re both in these transactional relationships to support their careers. There’s a moment when Ruth observes how these relationships speak to their early suburban childhood experiences. Neither come from wealth, and transactional relationships are one of the many ways in which artists support themselves. How did you decide to make this a shared element for these characters?

WAMBUGU: On one hand, it’s really crass to talk about the math you’re doing when you enter into a relationship in terms of its viability. But either both people in a relationship make money or one person needs to. But I think it’s not openly discussed. People tend to talk about relationships only in terms of love and, in fact, love is sometimes truly marginal. They’re both in these relationships to survive. Ruth gets into a relationship that also allows her to live the life of an artist, but she sees herself as doing something very different than what Maria is doing. She doesn’t feel like she’s doing something cynical.

JEFFERS: Right. She does express that she loves her husband. She might not have the utmost loyalty to him, but there’s less tension between them. He doesn’t just provide financial stability. He’s the more stable person in their relationship.

WAMBUGU: Yeah, emotionally as well.

JEFFERS: And that’s also a big thing in relationships between artists.

WAMBUGU: Of course, yeah. There’s a bit where I guess Ruth observes Marie and Sheila and basically says, “Couples can enable one another to behave so badly.” And sometimes I don’t even know if I wrote that scene in order to include that insight in the book or if I came to understand it in the course of writing the book. I feel like, as I wrote, I learned things about the world and learned things about relationships as well. One plus one does not equal two with relationships. It’s like, one dysfunctional person and another dysfunctional person actually end up exponentially worse than just their dysfunction alone.

JEFFERS: And Ruth sees herself as someone who doesn’t really get to behave badly. In her relationship with Maria, she is the more stable one. And she is sort of our everyman entry into Maria, the enigmatic subject of the book.

WAMBUGU: That’s a good way to put it, yeah.

JEFFERS: The book is centered around an intense homoerotic friendship. There’s a canon there: Elena Ferrante’s novels, Brideshead Revisited. Those books are all about class ascension. What made you want to write a book about this homoerotic, intense friendship, and then also this question of class ascension? The two themes feel linked in this very literary way.

WAMBUGU: Yeah, I think it’s true because the will-they-won’t-they is not necessarily, “Will these two women have sex or not?” It’s more so, “Will they marry and become upwardly mobile or not?”

JEFFERS: Totally.

WAMBUGU: And which one of them will opt in to the opportunities to be upwardly mobile through marriage? And I mean, without spoiling anything, they obviously do opt in to those opportunities, which feels like an inevitability just based on their childhoods. But I also think one of the examples in that canon you’re describing is Sula by Toni Morrison.

JEFFERS: Ruth reads Sula in the book, right?

WAMBUGU: Yeah, while working as a waitress. The backdrop in Sula is a sexual revolution. The backdrop in Lonely Crowds is certain technological advances or maybe a turn toward multiculturalism or different attitudes towards identity. Those are the more seismic shifts that are happening in my book. But in Sula, with both women, it’s not as though they find real wealth and real upward mobility, but they end up having comfortable middle-class lives. One of them, Sula, ends up completely taking advantage of and enjoying the sexual revolution. She has all these married sexual partners and acts as a complete foil to Nel, who marries and finds stability. And I guess the wisdom of the book is that both women end up dissatisfied. Nel’s marriage doesn’t last, and her illusions about her marriage are completely shattered. Sula longs to have this proximity to her friend again; she wants to come home and doesn’t want to be worldly in the way she initially imagined she did.

JEFFERS: Ruth and Maria share that perpetual dissatisfaction. There’s this constant thread of suffering, and Ruth and Maria seem to almost inherently understand suffering from a young age, not just because of their Catholic education, but also because Ruth witnesses Maria’s traumatic childhood and then Maria lives it.

WAMBUGU: With most women I know, it’s like you’re hardened by the time you’re 13 or something. The scales have fallen from your eyes. Which is interesting, because I think women are characterized as being really naive and not having a real understanding or acceptance of how the world works. But I often find that when you talk to a man, even a man that’s older than you, he’s having these revelations you maybe had as a child. Maybe a woman suffering is seen as frivolous, whereas a man suffering is seen as edifying and serious.

JEFFERS: Exactly. I was also wondering about the ways in which Ruth and Maria both resist narrativizing their own trauma. When they are children and Maria runs away, Ruth insists she doesn’t see it as a traumatic event. And Maria rejects authority in many ways, but she also rejects psychoanalysis when Ruth suggests it.

WAMBUGU: This is maybe more just my own feeling, but I don’t know that it’s such a consolation to try to narrativize trauma. We’re so encouraged to display our wounds to the world, and we’re told that visibility or attention will be a consolation or a form of recourse for things that have happened. But rarely does that happen. If anything, people pay attention for 10 minutes and you realize how disposable some of your most private pain is, especially when it comes to artmaking. It’s like, “Okay, you can only sell the most traumatic things that have happened to you maybe once.” And you’d be surprised how little value they have.

JEFFERS: That’s very true.

WAMBUGU: Sadly, people don’t really care. And also, maybe there’s something to be said about the strong silent type, and stoicism, and just accepting your suffering. Again, I’m not trying to be prescriptive. I don’t know that people should use the novel as a guide on how to live, but maybe that would be my advice. But I also was thinking of reading Rachel Cusk’s memoir of her divorce, Aftermath. There’s this bit where she’s walking with a friend who says, “You really need to tell your story. Narrative is the end of a relationship. Once you begin to narrativize a traumatic relationship, that’s when you can get over it.” And she says, “I don’t want to tell my story. I want to live.” And that felt very instructive to me when I read it. Even if you try to narrativize your traumatic experiences, you might not get them right.

JEFFERS: Right. Art isn’t healing, ultimately.

WAMBUGU: Yeah, it’s not even cathartic even.

JEFFERS: Also, this is a book about education and Catholicism and the idea of having something to rebel against. Where did that idea originate?

WAMBUGU: When you participate in religious rites or when you get a religious education, you’re taking part in a tradition, a very long, seemingly unending tradition. But with each generation, it gets more and more out of step with the surrounding culture. So I guess one consequence of that is that Catholic schools are just closing. There are just fewer Catholic schools. But another consequence is that the school’s kind of over-correct and maybe become more conservative than they would’ve even been in prior generations in order to respond to the fact that the surrounding world is becoming more and more secular.

JEFFERS: And that’s especially true in America.

WAMBUGU: You see it with American evangelicals or American Christians. It’s like they’re more conservative than Christians you’d find anywhere else. But I also wanted to say that, because I was raised with religion and I don’t really practice any religion anymore, I feel totally lapsed. Like, what are my kids going to write about? What are they going to write in response to if they want to be writers? For all these artists who were raised secularly, what material are they responding to?

JEFFERS: There’s a scene in the book when the girls are in school and they’re brought to this church in Providence to sing in the choir, and then they realize it’s a funeral.

WAMBUGU: That actually happened to me.

JEFFERS: I was wondering…

WAMBUGU: I was in the choir in school, and we had a field trip, and it was a funeral.

JEFFERS: They don’t even realize they’re having some sort of bizarre experience or a breakdown until it’s already happening.

WAMBUGU: I think that’s Kafka’s influence completely. His characters can really play it straight when they’re in the most absurd situations and really try to unravel the logic of an illogical situation. And I think that because Ruth narrates, she finds herself in these bizarre situations, and it’s like, “Okay, it makes a kind of sense. What sort of sense does this make?” She does play most situations quite straight and without a great deal of emotion.

JEFFERS: Yeah, she’s very logic-brained. And then when she becomes a teacher at Bard herself, she has this moment where she’s confronted by a student with a similar religious background and she doesn’t really know how to respond.

WAMBUGU: Mm-hmm.

JEFFERS: I mean, what do you think of the idea of an education in the arts? What led you to write about that?

WAMBUGU: I mean, for one, I wrote this book while I was at Columbia getting my MFA, so I was really receiving an education in the arts. I was curious about how to write about that experience without writing a novel about being in workshops, because that’s not terribly interesting. People flee a certain kind of more repressive education to go to art school in the hopes of getting something that’s more self-expressive or edifying or egalitarian, or whatever you project onto art school.

Then you go to art school and it’s just a school. It might be the School of the Arts at Columbia or NYU, but it’s just a small college within these massive universities that have interests which, at bottom, are no different from the interests of the business school. These schools all collect tuition, make money, and bank on the success of a handful of students. And not to be cynical, but I don’t think you’re going there to find a family. I think the romantic view of coming to New York to be an artist and to find community is sad. Of course, I’ve met wonderful people, but ultimately, wherever you go, you’re bringing yourself.