When James Baldwin landed in Los Angeles in mid-February of 1968 to continue work on a Malcolm X screenplay for Columbia Pictures, his arrival caused something of a media sensation. It also attracted the attention of the FBI, which was concerned that success in Hollywood would only amplify his subversive potential and the visibility of the Nation of Islam. Within a week, on February 21, a front-page article in Variety, with the headline “James Baldwin Can Only Write O’ Seas; Otherwise Engulfed in Negro Politics,” began: “Agent Robert Lantz…is meeting his client, James Baldwin, in Hollywood this week, in connection with ‘Malcolm X’…. Baldwin, who has found it difficult to work in America because of pressures on his time from militant and other Negro groups, finished the screenplay in London.” Noting that of late Istanbul had become his “writing retreat,” it went on to say that “Baldwin has been outspoken against some of the Negro racial extremists, hence his handling of the ‘Malcolm X’ script…. Hollywood now will concern itself with casting, etc., depending on the status of the screenplay.”

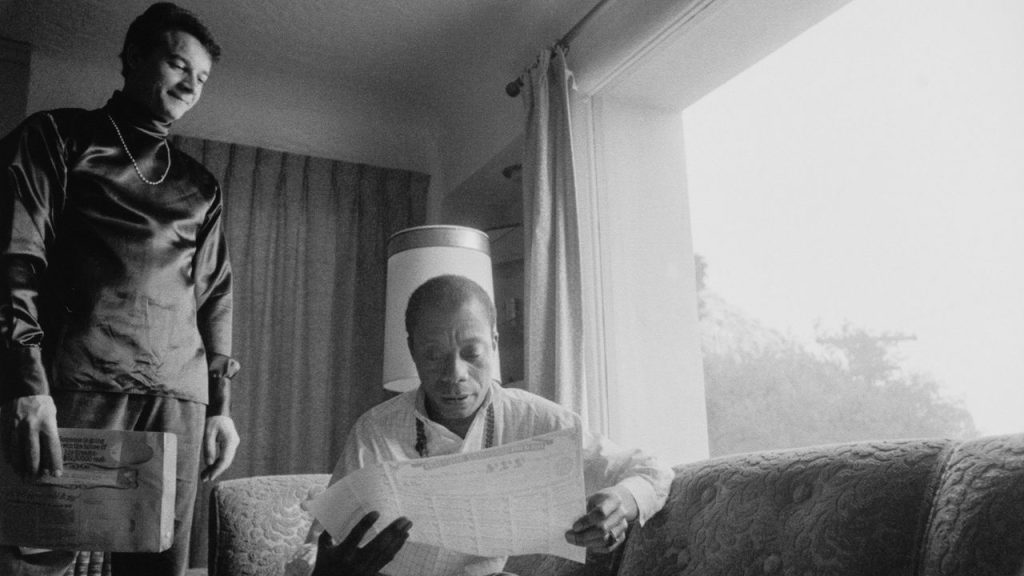

Baldwin was in a hard place, caught between several proverbial rocks: the mainstream demands of Hollywood, Martin Luther King–style politics, and the more radical positions of Black nationalists and the Black Panthers. By now he was far more aligned with the so-called Negro racial extremists (a fact that was not lost on the FBI, although their files consistently reveal their misguided concerns about his possible alignments with Elijah Muhammad), which was one of the reasons he was so intent on doing the Malcolm X movie himself and not leaving it to Hollywood regulars. Still, Hollywood was Hollywood. According to the Baldwin scholar Ed Pavlić, it was during this period that Baldwin wrote his younger brother David “about the strange scene of black radicals coming to see him at the Beverly Hills Hotel where Columbia Pictures had initially put him up. He told David that they’d come to ascertain if he was for real because he was in Los Angeles to tell the world about Brother Malcolm.”

When he sat for an interview with Hakim Jamal, founder of the Malcolm X Foundation, Baldwin was hammered with questions about living in France: “Why on earth would you go to a country that is predominantly white?” And his sexuality: “Are you a homosexual?” Baldwin replied, “No, I’m bisexual, whatever that means,” to which Jamal responded, “Good. No, I know, because that’s what they say anyway.”

Baldwin’s somewhat cagey responses were a product of what he later described as the conflict between “my life as a writer and my life as—not a spokesman exactly, but as public witness to the situation of black people.”

On February 17 he joined Stokely Carmichael, Betty Shabazz, and the chairman of the Black Panthers, Bobby Seale, at a much-publicized birthday celebration for Huey P. Newton in Oakland, the purpose of which was to raise funds for his release efforts. Then on February 23, two days after the published Variety article, Baldwin was already back in New York City for a tribute to W. E. B. Du Bois at Carnegie Hall, appearing onstage with Martin Luther King. In yet more evidence of how much he was being yanked around by dueling politics and the dictates of the entertainment industry, when he got back to California, Baldwin was relocated from the Beverly Hills Hotel to Palm Springs; Columbia hoped fewer political distractions would ensure his concentration on finalizing the script. As he later wrote, “Columbia couldn’t but be concerned about the time and energy I expended on matters remote from the scenario. On the other hand, I couldn’t really regret it, since it seemed to me in this perpetual and bitter ferment I was learning something which kept me in touch with reality and would deepen the truth of the scenario.”

And so, Baldwin was fine with the move to Palm Springs, at least in theory, as the hotel had “depressed and frightened me,” especially “the people in the bar, the lounge, the halls, the walks, [who] seemed as rootless as I . . . the only black person in the hotel.” But figuring out a way to stay true to Malcolm was proving to be a challenge.

Although he would soon return to Palm Springs, this particular stint was short-lived after King arrived in Los Angeles for a March 16 fundraiser held at a private home in the Hollywood Hills. He knew he shouldn’t be dashing off, but Baldwin felt compelled to attend with his good friend Marlon Brando, who was supporting King’s “Poor People’s Campaign.” Baldwin was asked to introduce King at the event, and his off-the-cuff remarks signaled both his support for King and the extent to which he had moved to the left of him politically: “It is not, as it was thought of ten years ago when Martin and those kids were marching up and down the highways, a Negro problem or a civil rights problem. What it is for all Americans now—and I mean this literally, from the bottom of my soul—is a matter of life and death.”

For his part, a visibly exhausted King (he looked “five years wearier and five years sadder,” Baldwin would later remark) was also moving to the left, if only by degree, in his call for “direct action.” It was King’s fourth event of that day alone, with two more sermons scheduled for the following morning; it was also the last time Baldwin would see him alive.