Priscilla Chan met the moment with the kind of grace and sensitivity she’d become known for. It was July 2020, George Floyd had recently been murdered, and staffers at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative—the foundation she started with husband Mark Zuckerberg in 2015—were hurting. Tissues on hand, eyes welling up, she hosted an all-hands Zoom to address them. “It didn’t feel right to not actually just spend the time as an organization acknowledging the—in medicine we call it ‘acute on chronic’—racial disaster that is our country,” she said, hands clasped in front of her, in a video obtained by Vanity Fair. If there was a silver lining, it was that the moment was so bad, change was imperative—both in the country at large and at CZI, whatever that would entail. “That’s my little hopeful pearl that I want to try to add.… We stand with the Black community, we stand with our Black employees. It’s felt harder and more important than ever to get a lot of our work right.” The work would take time, she acknowledged, but she implored her employees to “take care of yourself, make sure you’re giving yourself the space, the grace.”

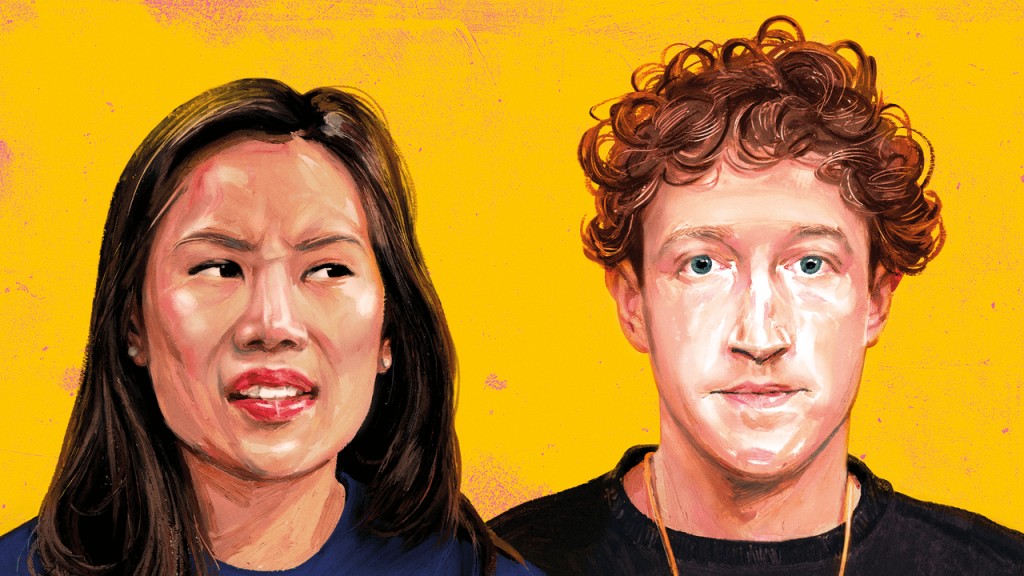

Four and a half years later, Chan appeared at President Donald Trump’s second inauguration, alongside her husband on the dais, a spot usually reserved for the president’s nearest and dearest. Zuckerberg had been cozying up to MAGA world for some time and had just come off an appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast where he, buff and in a new gold chain, ragged on the Biden administration and lamented a lack of “masculine energy” in the workplace. But to some, Chan looked uncomfortable at the inauguration, and the optics weren’t computing. Through CZI, she’d spent hundreds of millions on biomedical research, yet here she was standing a few feet from Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the new secretary of health and human services, a science skeptic. She appeared to make small talk with Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who was soon to cut billions in foreign aid, including for lifesaving HIV treatment in Africa. To many of Chan’s colleagues and admirers from the philanthropy world, the image was distressing.

To them, Chan represented—perhaps still does, they hope—everything antithetical to the president she was honoring. If Trump was their idea of a nightmare billionaire, Chan was their dream. They knew her to be unflashy and disciplined, driven by the conviction that everyone deserves a chance to overcome the circumstance of their birth. She was profoundly empathetic, easily moved to tears at the suffering of others. What could she have been feeling, some of those contacts wondered, celebrating such a gleefully callous man? Later, Zuckerberg posted a photo of the two of them in black tie on their way to an inauguration party he was cohosting with the caption, “Feeling optimistic.…”

Seven months into the administration that appears to be gutting everything she has held dear—scientific research, higher education, public health, caring for those in need—it’s hard to imagine that Chan, at least, is feeling optimistic, but she has remained largely silent. (Chan declined to be interviewed for this story.) Many former colleagues and admirers from nonprofit circles are searching for signs of the woman they knew and floating the questions. “I know they are separate people—and frankly, Priscilla comes off as a lot more human than Mark,” says Lucia Reynoso, a former CZI engineer, “but they are married and gave the impression of a united front.” So is she aligned with her husband? Has she been ideologically moved by the right-wing plutocracy? Or is she still working toward the greater good, maintaining her silence out of a sense of pragmatism?

If Trump had been president 50 years ago, Chan’s parents might never have found their way to this country. They were ethnic Chinese immigrants from Vietnam who had each fled the war-torn country by boat. They met upon arrival in the US, married, and settled in the working-class neighborhood of Quincy, Massachusetts. They worked in a Chinese restaurant and raised three daughters. Priscilla was the eldest. At the local public high school, Chan excelled in science and on the tennis court, became valedictorian, and got into Harvard on a full scholarship—the first person in her family to go to college.

It was there that she met Zuckerberg in October 2003, standing in line for the bathroom at a frat party. It was not his finest hour. He had just built Facemash, his “who’s hotter” website featuring images of Harvard girls side by side. The site had spread like wildfire on campus, and now he was set to go before Harvard’s Administrative Board. But one can imagine he fulfilled a need in Chan. She’d felt a sense of awe and alienation upon getting to Harvard, what with all the privileged, hypereducated kids in private school cliques. But here was one such boy, who’d gone to Phillips Exeter Academy, and he was interested. He was a brilliant nerd who, she found, “speaks in a whole new language and lives in a framework that I’ve never seen before,” as she told The New Yorker in 2018. He spent the months after they met building Facebook from his dorm room, then dropped out to go to Silicon Valley. Meanwhile, her life path presented itself to her when she met a girl from the Dorchester housing project, where Chan was mentoring. The girl’s front teeth had been knocked out. It was heartbreaking to Chan, a biology major, and it confirmed to her a calling—to serve children in need.

After she graduated in 2007, she joined Zuckerberg in San Francisco, where she taught science at an elementary school and then began medical school at UCSF. As a condition to her move, she made him commit to one date night a week and 100 uninterrupted minutes away from Facebook. He was then growing Facebook at warp speed—he’d turned down an offer from Yahoo to purchase it for $1 billion, and now, after an investment from Microsoft of $240 million, the company was valued at $15 billion. Chan told The New Yorker, “I had to realize early on that I was not going to change who Mark was.” But she could try to guide him in a world of real-life humans. They spent weekends together doing earnest activities like watching their favorite show, The West Wing (created by Aaron Sorkin, who would go on to write the screenplay for The Social Network), and playing Settlers of Catan, and in 2010 she moved in.

By that point, roughly one out of every 12 people across the globe had a Facebook account. Its promise was epic—to do nothing short of connect the entire world, and to help people “maintain empathy for each other,” as he told Time magazine, where he was named Person of the Year at age 26. In line with his status, Zuckerberg began honing his legacy. His hero had been fellow tech billionaire Bill Gates, who in 2010 launched the Giving Pledge, challenging other billionaires to promise to give away at least half of their fortunes before death. “I encouraged them to start early,” Gates says of early conversations with both Zuckerberg and Chan about philanthropy, noting that “Priscilla is leading one of the most ambitious scientific and philanthropic organizations in a generation.” Taking his cue, Zuckerberg announced with fanfare on The Oprah Winfrey Show that he would be donating $100 million to Newark public schools. The results of that effort were mixed, which educators have attributed to the project’s insufficient collaboration with the community. (A CZI spokesperson disputes the criticism, pointing to independent research that found improvement in graduation rates and gains in student achievement.)

Chan later told him that if he was going to be serious about education, he should probably have some real-life experience teaching. At her urging, he gave it a whirl by teaching a class on entrepreneurship at a Boys and Girls Club. Meanwhile, Chan was all in, doing high-stakes trauma work at San Francisco General Hospital. “It was gunshot wound after gunshot wound,” recalls a close friend. “She was the friend who’s always exhausted after doing a double shift.” She also took part in a special UCSF program designed to improve the health of underserved children. Facebook went public on May 18, 2012. Chan and Zuckerberg, now worth an estimated $19 billion, married the next day.

In 2015 the couple began two major projects, which they made a point of connecting: CZI and their family. After multiple miscarriages, Chan was pregnant with their first child. According to the recent memoir Careless People by former Facebook employee Sarah Wynn-Williams (whom Meta has legally blocked from personally promoting the book on the basis that she has potentially violated her contract), while Zuckerberg and his team were in Indonesia, he floated the idea to his coworkers that he might not be present for the birth—not that there was any particular conflict, just that something more important might come up at work. He relayed that he’d spoken with Chan about the possibility. As Wynn-Williams claimed, “[Chan] told Mark that she would be totally fine with him skipping the delivery but that he might come to regret missing the birth of his first child.” (“Mark was, of course, present from the beginning to the end of all three hospitalizations and deliveries for all three of their children,” says a source close to the couple. “This was not something they discussed.”) A few months before the birth, in September 2015, Zuckerberg attended a White House dinner and spoke with President Xi Jinping of China, where he was desperate to launch Facebook. Wynn-Williams claimed that he asked if Xi would do him the honor of naming his unborn child. Xi declined. They ended up naming the baby Maxima—“Max.” Zuckerberg had long been fixated by the Roman emperors and would go on to name their other two daughters August and Aurelia. (Careless People “is a mix of out-of-date and previously reported claims about the company and false accusations about our executives,” a Meta spokesperson said upon the book’s publication.)

Max’s birth coincided with the unveiling of CZI, which shook the philanthropy world. At its founding, the couple wrote a public letter to their new baby that both spoke of the promise of science and was suffused with Obama-era feel-good progressivism. “Our hopes for your generation focus on two ideas: advancing human potential and promoting equality,” they wrote. “Promoting equality is about making sure everyone has access to these opportunities—regardless of nation, families, or circumstances they are born into.” They announced they would be giving away 99 percent of their shares in Facebook in their lifetime, then valued at $45 billion, to the organization.