Looking back today, it’s amazing how many designers who became legend all started at just this time. (Or restarted—1983 was also the year that Karl Lagerfeld took over and totally reinvigorated the moribund house of Chanel.) Flipping through an issue of Vogue in 1983, you’d find spreads of the names to know: Gaultier, Azzedine, Rei and Yohji, Vivienne Westwood. We would go on to add many more. Punky, political streetwear out of London from Katharine Hamnett and BodyMap. Moody romance from Milan, by Romeo Gigli. A little later, the dreamy, intellectual so-called Antwerp Six, an ad hoc collective (they formed, loosely, in order to go Dutch on shared London trade-show space, the only way they could afford to do the show) that included Ann Demeulemeester and Dries Van Noten. My wife, Bonnie, who had joined the Barneys gang to manage shoes and soon was expanding her purview, discovered Dries with her team on the top floor of that trade show, with a slim rail of menswear. It was mostly white shirts, schoolboyish, simple. But Bonnie saw something in them.

Despite being based in Belgium, Dries knew Barneys. He had visited when he came through New York, back in the days of the Duplex, and been amazed that Barneys not only carried the likes of Mugler and the Japanese designers but even the most fashion-forward pieces by them, the runway pieces—the “strong pieces,” as he called them. Barneys was “an iconic store,” he told me years later. When Bonnie walked into his booth and introduced herself, he was so panicked that he actually ran away. “Luckily enough, I had a friend who was more business-minded, and she explained the collection in the first moments,” Dries recalled with a laugh recently. “It was only after 15 minutes that I cooled down and came back and was able to speak to them.”

Bonnie, unflappable as ever, was undeterred by his nerves, by the fact that it was a modest collection of mostly shirts, or that it was menswear. “Just make us 36 knee-length skirts and 36 floor-length skirts to go with it, and it’s going to be okay,” she told him.

Bonnie locked up an exclusive, and we kept it for years and years. Dries became one of Barneys’ proudest discoveries, and Barneys, one his biggest retailers.

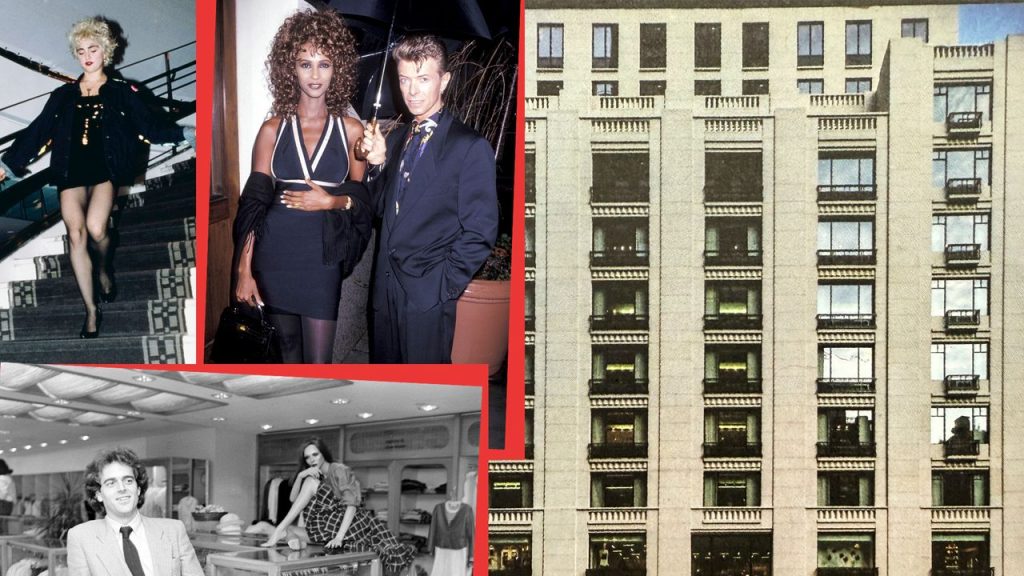

In the winter of 1985, I was doing the rounds on the fashion-social circuit, and went to the opening of the Met’s annual Costume Institute Gala. (They used to take place in December, not in May, as they famously do these days.) The Costume Institute was then under the creative direction of Diana Vreeland, the former editor of Vogue and one of the great fashion eccentrics. The exhibition was “Costumes of Royal India,” dripping in jewels and silks, not unlike La Vreeland herself. At the party afterward I ran into a guy I knew slightly, John Bodum, who by day did sales for a company called Go Silk, but was better known by night as the ultimate social connector.

John looked like the Mama Cass of the East Village, and he knew everybody: the schleppers of the Garment District, the party boys of the Pyramid Club, and every imaginable type in between. Another person he knew was a young installer on the Vreeland show, who had come from Los Angeles and was sleeping on his floor. In return for his services, Simon Doonan had been given two tickets to the party, and he gave one to Susanne Bartsch, the Swiss-born ga-ga club queen of downtown New York, and the other to John.

Out of my earshot, John elbowed Simon. “That’s Gene Pressman,” John told him. “You should really get to know him.”

The name was familiar to me. Simon was becoming known at that time as a mad scientist of window display, equal parts Dr. Frankenstein and Rocky Horror’s Dr. Frank-N-Furter. Born in Reading, in South East England, a place he couldn’t wait to leave, Simon was fashion-mad from birth. He escaped Reading for London, where he worked for Nutters of Savile Row, then decamped to Los Angeles in the late ’70s, where he landed at Maxfield. Tommy Perse, Maxfield’s founder, sold much of the same avant-garde European fashion that Barneys did, though doing so made him much more of an outlier in bad-style LA than we were in sophisticated New York. Maxfield, much more than Barneys, was known for black everything—“Whatever Perse wants and can’t find in black, he has made-to-order. In the past, that’s included bicycles, combs, hair dryers, hangers and linens,” the Los Angeles Times once reported—and all-black can be a drab downer. What Maxfield needed was humor to lighten it all up, and that was Simon’s specialty.