The last time anybody saw Charlotte Cook was January 3, 1974. That afternoon, the college student and community organizer, a young mother and widow, left her home in Oakland to visit her sister in San Francisco, decked out in disco-era style: knee-high boots, a blue sleeveless blouse, and a camel hair coat. When her body was discovered the following day at the bottom of a bluff overlooking Thornton Beach in Daly City, California, a brown belt wrapped around her neck, it was the description of her “expensive camel’s hair coat” in local press reports that led her father to identify her. She was 19.

Cook’s daughter, now 52, says that when she was growing up in her great-grandparents’ home, nobody in their close-knit family, not her great-grandparents, not her aunts or uncles, would ever talk about her mother. Any time the name Charlotte Cook came up, a hush would descend over the room, indicating the topic was off-limits, too painful. “I never knew what to think,” says Freedom Cook, a massage therapist, activist, and preschool teacher in Vallejo, California. “I just thought I had a mom and she was just out in the world somewhere, and I don’t know what happened.” Freedom was 12 when one of her aunts finally informed her that her mother was dead.

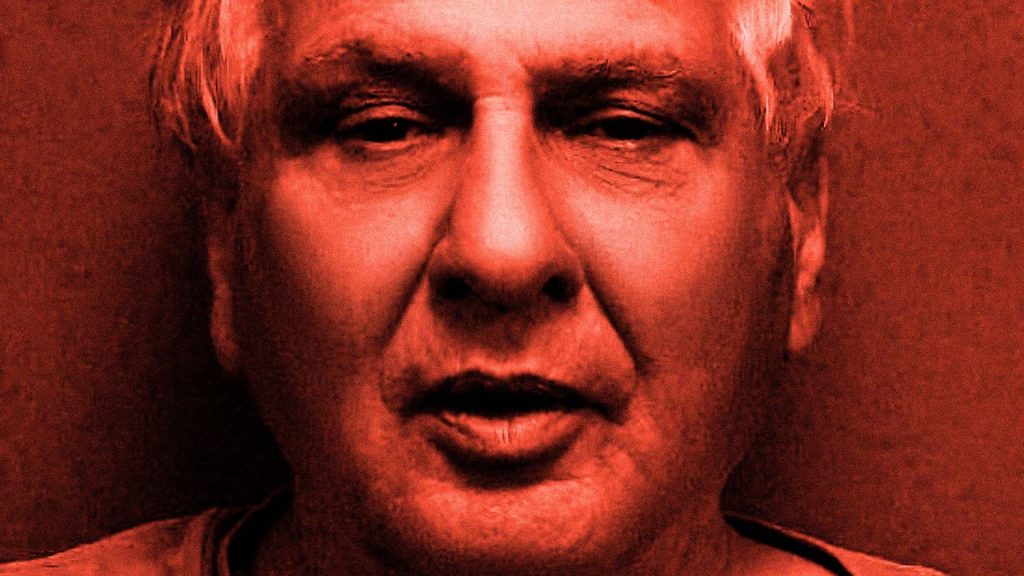

For decades, nobody knew who was responsible for Charlotte Cook’s death. Then, in January, Freedom was shocked to learn that the man who murdered her mother was almost certainly Joseph Naso, a 91-year-old convicted serial killer, a death row inmate at California’s San Quentin prison. Even more surprising was that Charlotte’s murder—Daly City’s oldest “active” cold case—was solved not by the local police but by William A. Noguera, another convicted murderer at San Quentin. Noguera, who served 36 years on death row, calls himself “the Jane Goodall of serial killers” because he’s spent more time embedded with them in their habitat than practically anyone, including FBI profilers and forensic psychologists. One of the killers he closely observed on death row was Naso.

In spite of overwhelming evidence, Naso has never publicly admitted to killing anyone. But during the 10 years that Noguera overlapped with him at San Quentin, Noguera says he got him to reveal his secrets by pretending to be his friend and protector. Armed with 300 pages of notes about his interactions with Naso, containing descriptions of alleged victims and the timing and circumstances of their deaths, Noguera then wrote to Kenneth Mains, a cold-case detective he saw on TV, and persuaded him to collaborate with him to identify more victims. Thus far, the convict-cop duo has linked Naso to four unsolved murders, and they are working on solving several more.

Mains, a compact man with a -closely cropped gray beard, arms covered in sleeves of tattoos and a large cross dangling from his neck, admits “it’s an unlikely friendship, convict and cop,” adding that without Noguera, “none of this would be happening.” Although he’s based in rural Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, Mains is currently in contact with the San Francisco office of the FBI and is providing intelligence to six police departments across the country, including Northern California, Las Vegas, and Rochester, New York. Mains and detectives involved with investigating the cold cases believe that Naso, convicted in 2013 of four murders, is possibly responsible for as many as 22 more. That would make Naso among the most “prolific” serial killers in American history, perhaps more deadly than better-known murderers like Ted Bundy (20 victims), Jeffrey Dahmer (17 victims), and Richard Ramirez (13 victims).