Vidal returned to these themes in “The War at Home,” the first VF essay of his I edited. He warned that the country was coming apart not just from imperial overreach of what he liked to call the Cheney-Bush oil-and-gas junta, but also from neglect at home. He saw a nation of people dispossessed, farmers forsaken, workers abandoned, pointing to those left behind by the new economy and a political class (in both parties) deaf to their grievances. “[T]here are vast areas, like rural America, that are an unmapped ultima Thule to those who own the corporations that own the media that spend billions of dollars to take polls in order to elect their lawyers to high office,” he wrote. He predicted that popular resentment would not remain latent—that it would be harnessed by demagogues who spoke in the language of populism while advancing the interests of entrenched power. At the time, critics waved it off: Vidal being Vidal. Today it reads as a forecast of the politics of grievance and resentment that would fuel the rise of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement.

The U.S. Bill of Rights is being steadily eroded, with two million telephone calls tapped, 30 million workers under electronic surveillance, and, says the author, countless Americans harassed by a government that wages spurious wars against drugs and terrorism.

One morning, soon after “The War at Home” was published, I arrived at the magazine’s offices, and my assistant, Marc Goodman, told me there was a letter on my desk that I should look at right away. Many pages, handwritten in tiny script on yellow lined paper, it was from the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh, with a return address of the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. There was a Post-it on the first page: “Hey Matt, please pass this on to Gore. —Tim.” It was duly faxed to Ravello. Vidal called, aglow. McVeigh had been studying the Bill of Rights while on death row and reading a lot of Gore Vidal. The two started a correspondence about their mutual interest in the erosion of the Bill of Rights, which became the basis for another essay, “The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh.” In that piece, later selected for the 2022 edition of The Best American Essays, Vidal set out not to excuse McVeigh’s atrocity—he was careful to note that nothing could justify the killing of 168 people, including 19 children in the day care center of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City—but to place the bomber’s fury in a wider American context. He argued that McVeigh’s rage over Waco (a federal siege ending in the deaths of 82 people) and Ruby Ridge (a raid in Idaho that left three dead), along with his distrust of an unaccountable federal government, reflected a deep alienation shared by millions, especially neglected rural and working-class Americans. The reception was explosive: Critics accused Vidal of giving a platform to a mass murderer, even as he stressed that he did not condone the bombing and insisted that McVeigh’s mindset revealed the sickness of the republic. McVeigh, who invited Vidal to witness his execution in June 2001, became a kind of dark mirror to Vidal’s analysis. Vidal made plans to attend the death by lethal injection but canceled at the last minute. “He’s a harbinger,” Vidal told me. I was not sure I completely believed him at the time, but that harbinger now looks an awful lot like one foreshadowing the arrival of Trump and the MAGA movement, which have been very effective at channeling the same grievances into political power. That brings to mind another Vidal line: “The four most beautiful words in the English language, ‘I told you so.’”

Gore Vidal’s 1998 Vanity Fair essay on the erosion of the U.S. Bill of Rights caused McVeigh to begin a three-year correspondence with Vidal, prompting an examination of certain evidence that points to darker truths-a conspiracy willfully ignored by F.B.I. investigators, and a possible cover-up by a government waging a secret war on the liberty of its citizens.

Editing Vidal was an adventure on many fronts. In the lush days of Condé Nast’s bottomless expense accounts and budgets, lavish gifts were the norm when a star writer turned in a big piece. Vidal drank gin by the gallon (to wash down the Macallan 12), so once I sent a case of Bombay Sapphire to Ravello. Turns out the gin had to be driven 170 miles from Rome. The fax machine soon spat out a page with his scrawl: “Mother’s milk arrived with trucker’s compliments.” There were other contributor perks. He could only write his essays on vintage portable Olivetti Lettera typewriters (novels were composed in long hand on legal pads). The Olivettis were getting harder to repair, so my assistant found a trove of them and ordered the lot. We kept about a half dozen in the office to FedEx to Italy for stuck keys and other technological emergencies. Once, when Vidal was on deadline and staying in his usual suite at The Plaza in Manhattan, an Olivetti was messengered over for him. He and I got back from a long, wet dinner at the restaurant Daniel, and he sat down to write while I was still there. I was amazed to see that he composed those long, intricate essays using one finger, pecking out a single letter at a time. A typist was hired to create a final draft from the messy, marked-up Olivetti typescripts, and he never dropped a stitch in his copy. He was probably the only writer in the history of the magazine allowed by the revered copy chief, Peter Devine, to invent a word. It was the adverb sickenly, a short version of sickeningly, that Devine let slide, saying, “After all, it’s Gore Vidal.”

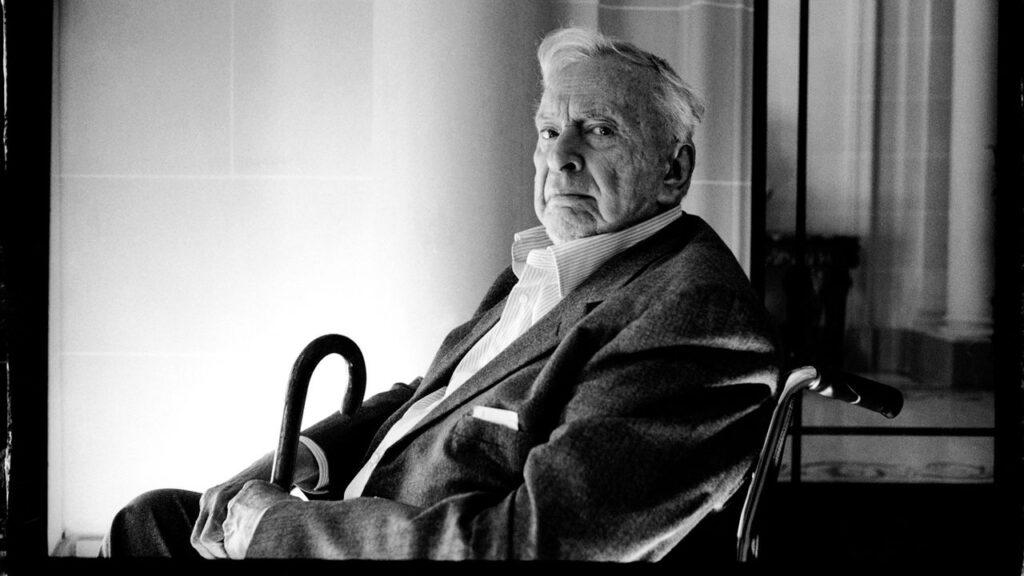

As Vidal and I grew closer, I made trips to Ravello to visit him and his companion of more than 40 years, Howard Austen. They lived at La Rondinaia, a vast four-level villa built into the side of a sheer cliff and surrounded by terraced gardens, overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea. The world came to Vidal in Ravello. In the guest rooms there were silver-framed photos of famous previous occupants: Johnny and Joanna Carson, Lauren Bacall, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, Leonard Bernstein, Rudolf Nureyev. When Hillary Clinton paid a visit in 1994, La Repubblica’s headline was “Lady Clinton nel Paradiso di Vidal.” It was there that the Maestro could read and write with the distractions of the modern world kept at a safe distance, while Austen dealt with all quotidian matters. An admirer of his paternal grandfather, the populist Oklahoma senator T.P. Gore, a man of the 19th and early 20th century, Vidal identified more with those pretech times. I think it helped him conjure the distant pasts of his historical novels, which were meticulously researched and scrawled out on yellow legal pads. (His book 1876 landed him on the cover of Time magazine in 1976, but Burr and Lincoln are his two masterpieces of the genre.) His only nod to the digital age was his fax machine, which made sending manuscripts a breeze. He called his hi-fi “the victrola” and hadn’t driven a car in decades. He walked the stairs and terraces of the Amalfi Coast daily, which I think contributed to his relative longevity, despite levels of alcohol consumption that were hard to reconcile with such a staggeringly prolific career. He prided himself on never drinking on the job. While staying with him, I noted that he worked regular hours, reading and writing in his book-lined studio overlooking the sea from 10 a.m. until lunch. He then went back to work until, as he said, “the shadows grow long”—cocktail hour—about 5 p.m. He pronounced to me once that his doctor told him he had “a perfect liver.” And true, it never gave out. When his feuding rival of the ’60s and ’70s, Truman Capote—who Vidal frequently claimed did drink while working—died at the home of Joanne Carson, one of his “swans,” in 1984, Vidal’s infamous response was, “Good career move.” Their fractious relationship blossomed into a lawsuit in 1975. Thereafter, Vidal dismissed Capote with the line, “I saw him only once again, in 1968, when, without my glasses, I mistook him for a small ottoman, and sat down on him.”

Vidal campaigning as the Democratic candidate for Congress for the 29th Congressional District of New York in Poughkeepsie, April 7, 1960.Ben Martin/Getty Images.