Another character parallel was the restless John Raskob, who became one of the wealthiest men in the country by revolutionizing the automobile industry. Money alone failed to satisfy him, so Raskob got involved in politics (where he was despised), wrongly assuming that his wealth could be weaponized for political purposes. And in his downtime, he sired 13 children. Sound familiar? He’s the Elon Musk of Sorkin’s narrative. Both men were seemingly “never satisfied,” Sorkin says.

Then there is the stock trader Jesse Livermore, who was able to maintain his allure in the press by “planting stories and issuing elaborate denials to provocative questions,” even though he squandered several fortunes. The first comparison that came to mind was Billions’ Bobby Axelrod, who manages a multibillion-dollar hedge fund. He also compares Livermore to Bill Ackman, the Pershing Square Capital Management CEO, who has become a media constant over the last few years.

Throughout the book, Sorkin chronicles the attempts of these business leaders to move the markets, both for personal financial gain and to reassure the public that there was nothing to worry about as the house of cards started to collapse. Most of the financial coverage at the time was “relatively obsequious,” Sorkin tells me, adding that investigative journalism in the sector was uncommon given the novelty of burgeoning Wall Street celebrity. The shine wore off around 1931, but it was too late for warnings by that point. Sorkin argues that by 2008, journalists had started to learn from their mistakes, setting off alarms for years of a real estate bubble that could burst at any moment. But, he says, “by default, if our job is to blow the whistle, you can argue we didn’t blow it loud enough.”

Even still, CEOs and business leaders use the media as a tool to move the markets and cozy up to journalists. Sorkin acknowledges that he encounters this frequently given his platform. Fink may have been doing something like that with his Davos Squawk Box appearance, signaling his hopes for Trump’s SEC. It’s something of a trade hazard when the president is a well-known cable news obsessive.

If the question is whether the US is walking into another financial crisis like 1929 and the Great Depression, Sorkin isn’t ready to draw that conclusion. Most financial crises are a function of debt and too much leverage in the markets, he continues, “and part of the problem is we don’t know whether there is, because so much of the leverage in the system is now in sort of the shadow banking system.” The events of 1929 should serve as a warning, not that we are necessarily on the cusp of a financial crisis of that magnitude, Sorkin argues, but that if lessons aren’t learned, “we could go down the same road.”

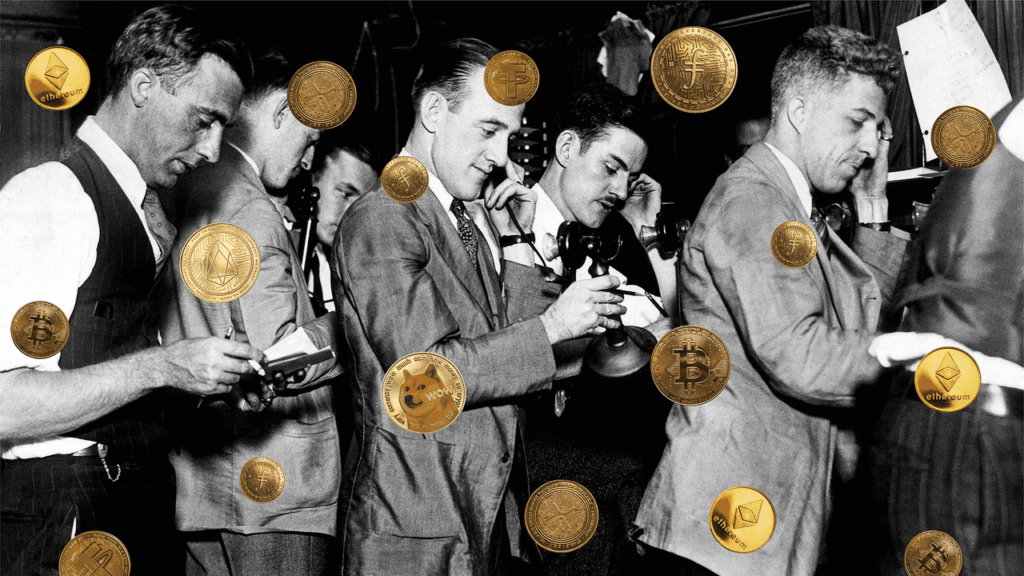

And, as any crypto investor who may have been put on to SorkinCoin by a stock-pool-esque group chat by now surely knows, nothing good lasts forever. At press time the unit was trading at $0.00008786.