Because Lafferty died in 2016, Shackleton worked with the late officer’s family to secure the rights to his fairly obscure book. The filmmaker was in the Bay Area, deep in preproduction, when he learned that the family had reversed course and decided against making a deal.

“I was gutted, but I completely assumed, give it two weeks, three weeks, I’ll get over it, I’ll move on,” Shackleton tells Vanity Fair. Instead, “I found myself traipsing around London, hanging out with friends and seemingly every night, just reeling off scenes or entire narrative arcs from this film that would now never come to be.”

Instead of a typical true crime feature or series, Shackleton decided to make the Zodiac Killer Project—a movie, opening November 28 in San Francisco, in which he’d explain exactly how he would have made a doc based on the now-verboten Silenced Badge. The approach is not quite having your cake and eating it too, but it’s close.

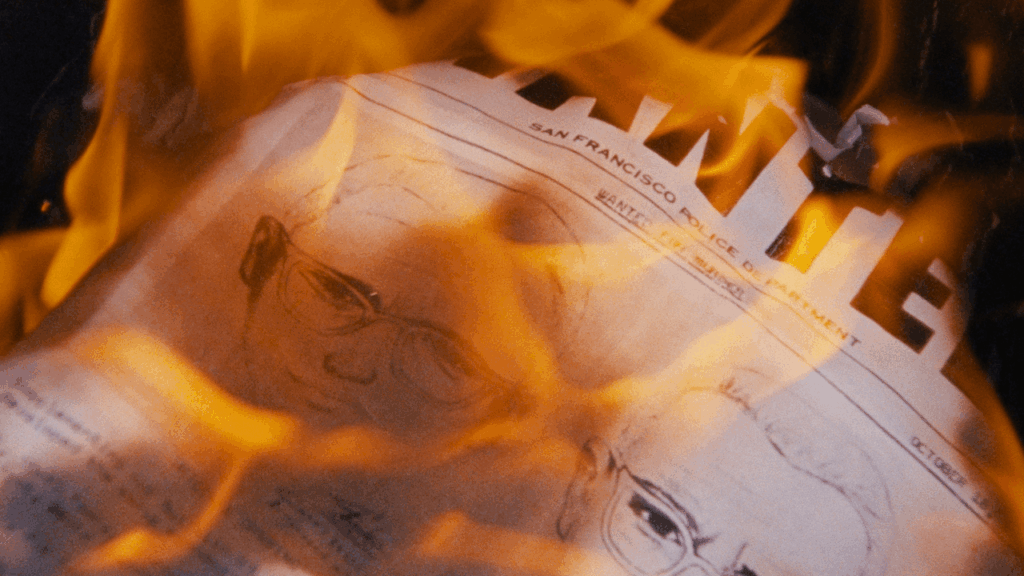

Shackleton returned to the Bay Area in the summer of 2023 to capture footage of Vallejo highways, small NorCal towns, and that fateful rest stop. That—as well as short moments of reenactment Shackleton laughingly refers to as “evocative B-roll”—is mostly what we see as the director explains, beat by beat, how his theoretical film would have played out.

Shackleton lays bare how rote “prestige” true-crime documentaries and docuseries have become. While announcing when the initial credits would roll, he juxtaposes clips of similar title sequences from such high-profile projects as The Jinx and Making a Murderer. “All these things are built to the same model now,” he says. He’s right. It seems every show begins with similar grayscale, layered, out-of-focus images of landscapes, birds, newspaper clippings, and the ubiquitous male figure, suspiciously slinking away.

That’s just the first in a series of sharp jabs Shackleton takes at true crime. Name a standard moment from a buzzy docuseries, from someone saying that a small town has a dark side to the use of red in a reenactment to make a suspect appear more sinister, and Shackleton will admit—with a mix of sarcasm and wistfullness—that he would have used that same tool. The boilerplate array of victim photos is grounds for perhaps his sharpest critique: “That’s when you know these shows really care,” Shackleton says. “When they end with a black-and-white photo grid of all the victims.” He would have closed his film with one had Lafferty’s family been willing to play ball.