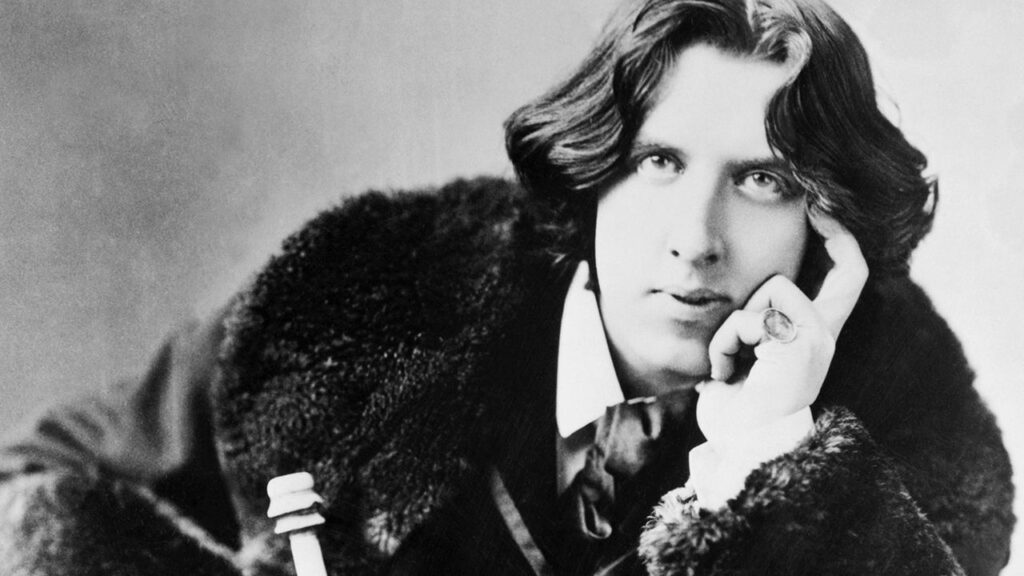

In the mid-1990s, Merlin began writing a biography of “the posthumous existence” of Oscar Wilde. Nearly 30 years later, he finished it. After Oscar: The Legacy of a Scandal was released last month in the UK by Europa Editions, ahead of its publication in the US next April.

So, what took so long? “Having criticized other people for sloppy research and inventions and exaggerations and so on, I knew I had to get it right myself,” Merlin, 79, tells me during an interview over Zoom from his home in the Burgundy region of France, where he lives with his wife, Emma, who teaches English to employees of the French nuclear industry.

As Merlin investigated the details of Wilde’s tragic last years and charted the dramatic swings in his literary reputation in the century following his death, his book became a family memoir as much as a scholarly biography. Combing through letters, diaries, and photos (many not published before), he eventually came to terms with his complicated legacy.

Given how celebrated Oscar Wilde is today, people might find it hard to fathom “the ricochet effect of the atom bomb of the Oscar Wilde scandal,” as actor Rupert Everett phrased it during a launch event for After Oscar at the British Library on October 16 (which would have been the author’s 171st birthday). “But it’s a ricochet that you are still living,” Everett said to Merlin.

During my chat with him, Merlin elaborates: “I wanted people to know that the echoes of that scandal back in 1895 can still be heard—faintly, admittedly—right up to the last 20 years.”

He also explains why his last name isn’t Wilde. Soon after Oscar Wilde began serving his sentence of two years’ hard labor in 1895, his wife, Constance, adopted the surname Holland for herself and the couple’s two boys, Vyvyan and Cyril, who were eight-and-a-half and 10 years old at the time. Given the scandal that convulsed Victorian society, it was, he writes, “a necessity dictated by public prejudice and concern for her children’s future rather than any sense of shame on her part.”

Prior to his fall, Wilde was the toast of London. He and Constance, the daughter of an Anglo-Irish barrister whom he married in 1884, were bringing up their boys in their home on Tite Street. It was there that she met her husband’s beautiful younger lover, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, a son of the Marquess of Queensberry, when Wilde brought him for a visit. In 1895, the marquess visited the Albemarle Club in London, where the Wildes were members, and left a message with the porter accusing Wilde of being a sodomite. Goaded on by Bosie, who loathed his father, Wilde brought a libel action against the marquess. He later withdrew the libel case, but the Crown then successfully brought charges of gross indecency against Wilde.