Photos by Emilio Madrid.

SUNDAY 4:31 PM DECEMBER 14, 2025 QUEENS

———

ALEX

MEL OTTENBERG: I’m waiting for this guy dressed like a cheeseburger to talk to me.

ALEX: Hello.

OTTENBERG: I’m ready to grill you, Mr. Cheeseburger.

ALEX: We’ll need it well-done.

OTTENBERG: Let’s go.

ALEX: Grill me past well-done if you need to!

OTTENBERG: Where’s the best burger in New York City?

ALEX: For me, it’s cliche, but 4 Charles Prime Rib does the most exemplary burger I’ve had in my life. In terms of composition, simplicity, and execution of the ingredients, no burger comes even close.

OTTENBERG: What is the distant number two?

ALEX: Let’s see. Emily in Clinton Hill is fantastic. Sailor in Fort Greene, similarly delicious.

OTTENBERG: Fantastic. Alex, tell me your New York story in a few sentences.

ALEX: I grew up in Bushwick, moved away to Jersey, then all the way to Utah. College in North Carolina, A year in Atlanta, made it back here. Fell in love with the city by spending far too much money eating out at restaurants, appreciating the burgers, the food scene, the different cultures that come to cater to different communities out here. And as such, I feel like I have been able to experience, once again, the beauty of the city’s cultural tapestry, its diversity, and the meals that feed its people.

OTTENBERG: What did you talk to Zohran about today?

ALEX: I spoke to him about what his plans would be to support the restaurant industry and particularly immigrant restaurant workers, as their current status in the United States is at risk through the current presidential administration. I hope to express to him the importance of protecting these workers because New York’s restaurant industry depends on them to simply survive. And without them, what we know as the beauty of eating out would simply cease to exist. So I spoke to him and made it urgent the point of protecting these restaurant workers so that they can continue to sustain the restaurant industry and make the city as beautiful and as culturally rich and vivid as it is.

OTTENBERG: So what was the vibe you got back from Zohran?

ALEX: Energy that I feel like is unprecedented, especially for somebody that is a leader. For him to be leading New York presents an opportunity both for the city to emerge as better and more empathetic for everyone, but also for the city to look at difference as an asset, not as something that stokes division.

———

MARIAM & BATYA

OTTENBERG: What’s up? How are you doing?

BATYA: Hello, my name is Batya.

OTTENBERG: You just talked to Zohran?

BATYA: Yes, I talked to Zohran.

OTTENBERG: How was it?

BATYA: It was really nice. He was really friendly. He was taking notes, asking me questions about the stuff I was talking about. I was talking to him about the bad infrastructure on Staten Island and how we have very poor public transportation. I asked him, as mayor, if he can please invest in Staten Island because we’re always left behind. He was very responsive. I told him a bit about school and some research I’m doing because I’m in a fellowship in my school where we’re researching the affordability crisis in New York City. All the students who I’m doing this with are really inspired by him and the work that he’s doing, so I told him that. It’s really a nice opportunity to actually have this conversation with an elected official.

OTTENBERG: You’re doing real civic duty, and I’m just covering it, but it really is wholesome and wonderful to be here. Mariam, who you’re sitting here with, was telling me the same thing about how you guys don’t have trains, so you really need the buses. Do the buses suck?

BATYA AND MARIAM: [In unison] Yes!

BATYA: I got the closest bus line near my house, the S93. It connects Brooklyn and the College of Staten Island, which I attend. It’s so annoying that it doesn’t run on weekends. It also doesn’t run on federal holidays. It stops running at 10:00 PM. And it’s so annoying that I spoke to my councilman about it and he emailed the MTA about it. They were just like, “Oh, cope, I guess. We’re not going to address this issue.” I’ve been ranting about how annoying it is to so many people, so I seized this opportunity to let Zohran know. So let’s say you’re a student and you want to take weekend classes, you have to take two buses to get to school, and then you’re late to your class and then you have to withdraw from the class if you’re late too much. So I just had to step up and talk about this. He was really receptive and it was just a really good opportunity.

MARIAM: I love the buses and I really want them to work for Staten Islanders. I’ve been a lifelong commuter my whole life. I was born and raised in New York City and I’ve taken the bus for as long as I can remember. So what I really want to add to the conversation is that I want them to be reliable. I want them to be fast and free. I know there’s been a lot of times when I didn’t take the bus because I didn’t want to pay the fare. I can just combine all my errands in one day instead of going out multiple times, different days. Or sometimes, you expect it to show up and then it just disappears.

BATYA: Happened to me this morning.

OTTENBERG: It’s a nightmare.

MARIAM: Buses are a lifeline for Staten Islanders, especially the North Shore. I want to emphasize that because a lot of South Shore Staten Island is car-centric, they drive everywhere, but the North Shore, we rely on the ferry, and to get to the ferry, you have to take a bus. It’s been unreliable my whole life and I want Zohran to change that.

OTTENBERG: Wow. Batya, what’s your New York story in a few sentences?

BATYA: I was born and raised in Brooklyn. Then my family wanted to finally buy a home and when home prices in Brooklyn are too expensive, what do Brooklynites do? They moved to Staten Island. So I’ve been living there for the past three years and it’s a big shock moving from Brooklyn, even though I live in South Brooklyn, which isn’t the biggest transit haven. But Staten Island is abysmally worse. It just shocked me to my core and I had to do something about it. And I guess through that, I’ve been more engaged in civic stuff and I just really want the city to be a better place.

OTTENBERG: And Mariam, what’s yours?

MARIAM: My parents immigrated here from Bangladesh and then I was born and raised on Staten Island. So I am a lifelong Staten Islander, lifelong New Yorker. I went to New York City public schools my whole life. I’m also a CUNY undergraduate, so I lived here my whole life. I love it here. I also love Staten Island. A lot of people give Staten Island a bad rap, but New York City is my home and I want to stay here because my parents built themselves up from nothing when they came here. And being in New York City was such a privilege because a lot of the city invests in the students, the children, the youth of New York City, and I don’t want that to go away. I actually want to see that invested in more because those were the programs and services that uplifted me and my family. I was able to graduate college, get a great job. I want to stay here, but it’s really hard to stay here because of the affordability crisis, essentially.

BATYA: New York City is the greatest city in the world. There’s people from all over the world here and it’s just such a unique city and I really want to stay.

OTTENBERG: New York’s a piece of shit but I love it.

BATYA: New York is my toxic situationship. [Laughs]

OTTENBERG: I don’t want to leave either, but it’s so expensive.

MARIAM: It’s so expensive. A lot of people that just work regular, working-class jobs can’t even survive here. That’s the heart of the city. That’s what we want. We want those people to stay. Those are the people who make culture.

———

BEAU

OTTENBERG: Hey, what’s your name?

BEAU: Hi, my name is Beau.

OTTENBERG: Hey Beau. What neighborhood do you live in?

BEAU: I’m in Prospect Heights.

OTTENBERG: Tell me a little bit about your New York story. Short version.

BEAU: Oh my gosh. I’m a transplant. I moved here from the south. I’ve been here for 10 years and yeah, I love it. It’s the safest place for me to be as a trans person in New York City. I’m excited to be here.

OTTENBERG: How did you end up here today?

BEAU: I found out on Instagram, signed up, and maybe in a couple of hours I was registered to attend, so it was a super quick and easy process.

OTTENBERG: And Beau, what did you speak to Zohran about today?

BEAU: I talked about extreme heat and climate risk as it relates to communities of color across the city. He was super well-versed in some of the technologies around extreme heat and flooding, so I was very impressed to see how much he knew about the topic and innovative technologies.

OTTENBERG: What are you most excited for for New York next year?

BEAU: Just to see what happens. There’s a lot of talk and theory and all that kind of stuff. I’m just excited to see some change, hopefully for the better. To see Qween Jean really engaging very closely with Zohran is very inspiring, and all that she’s done for the Black and trans community. I’m excited to see some new people show up in places maybe where they haven’t been, to see some of these new ideas being tested and put into action. It’s what we’ve all been voting for.

———

THADDEUS & GLORIA

OTTENBERG: All right. I’m here with Thaddeus and Gloria. Where do you live?

THADDEUS: We live in Bed-Stuy.

OTTENBERG: What’s your New York story, the short version?

GLORIA: Me, I’m a child of immigrants and have been working in this city since the early oughts. A hustler, that’s my story.

OTTENBERG: I’m with it. Thaddeus?

THADDEUS: I’ve been organizing mutual aid in New York City since I was a teenager. I set up the first community fridge in the city in 2020. I came here to talk to Zohran about that because a few years ago we had over a hundred in the city and now we have less than 60 because it’s hard to find places to host them.

OTTENBERG: And a community fridge is what?

THADDEUS: A community fridge is a refrigerator that’s out in public space, accessible 24-7. Anyone can put food in, anyone can take food out. It’s a solution to hunger and a solution to food waste.

OTTENBERG: So that peaked in COVID 2020 and now we still need it?

THADDEUS: Yeah, absolutely, especially with threats to food stamps, and also what’s happening to federal budget cuts that are shutting down pantries throughout New York City.

OTTENBERG: How did the conversation go?

THADDEUS: It went great. He asked the right questions and he took copious notes.

OTTENBERG: Cool. Anything you want to add?

THADDEUS: Yeah. I spoke to the deputy mayor. That was a bit of a longer conversation and he expressed support and said that the city administration should be picking up some of the slack and filling in the stop gap for the loss that we as a city are suffering as a result of what’s happening at the federal level.

OTTENBERG: Fantastic. Well, great talking to you.

———

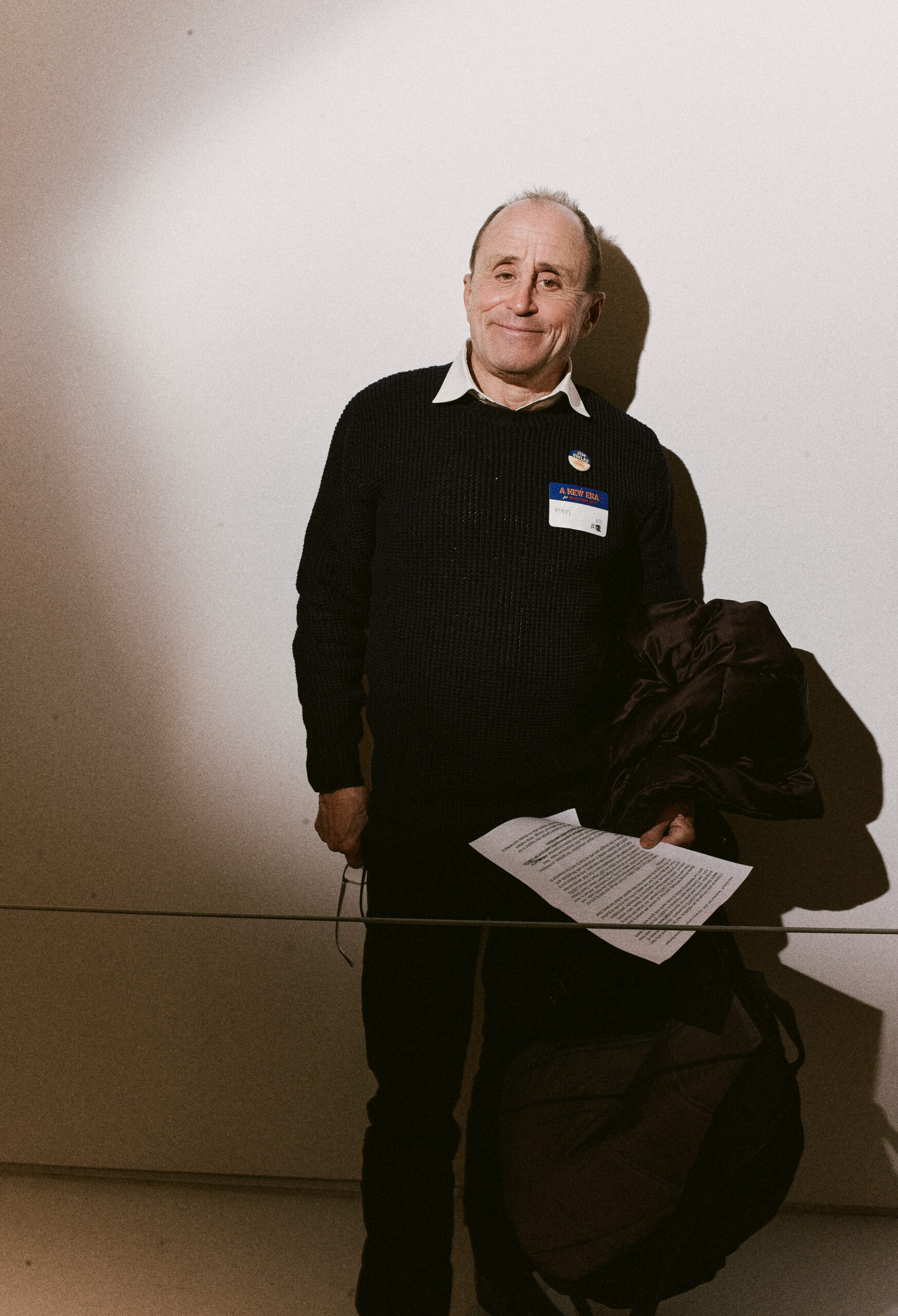

ALAN ROSKOFF

OTTENBERG: You looked like you’d have an interesting story that was different from everyone else’s, which is why I grabbed you. What’s your name?

ALAN ROSKOFF: My name is Alan Roskoff. I’m president of the Jim Owles Liberal Democratic Club, and I co-authored the nation’s first gay rights bill in 1971.

OTTENBERG: Fuck yeah. Thank you.

ROSKOFF: You’re welcome. Actually, the first gay rights bill in the world.

OTTENBERG: How did you make it work?

ROSKOFF: 11 years of lobbying and educating elected officials, galvanizing various communities. I mean, it was a new issue to so many of these people. And even those that supported us in the beginning didn’t realize how much hate there was out there. And with religious communities and the police and the fire department, it became a real battle—one of the foremost, most controversial areas of civil rights in New York. It was the time of the feminist movement, the black civil rights movement, so we all formed our movements and made our progress together.

It’s amazing how long it took. We had a lot of people working against us, a lot of great people who came forward, and life has changed so much for LGBTQ people. I’ve been involved with mayoral administrations since John Lindsay. I’m very excited about the new administration, Mayor Mamdani, because I have confidence that he will have LGBTQ representation at the highest levels, including people who have given their blood, sweat, and tears to get us where we are today. As I just told the Mayor-elect, it’s important that those of us who are in the trenches, those of us who have been beat over the head by police officers, those of us who have spent nights in prison, be part of policy decisions.

OTTENBERG: Yeah, because it’s clear that we can’t just assume that everything that you guys went through on behalf of future generations, like myself, isn’t going to happen again in America.

ROSKOFF: In many ways it is happening again. Parents of trans people are disowning them. They’re being discarded. They’re lives are being made miserable in schools and all. It’s kind of similar to what gay people went through in the ’70s.

OTTENBERG: Yeah. What was Zohran like?

ROSKOFF: Oh, the meeting was great. I love him. I’m so excited that he won. We worked for his victory, and the club endorsed him, and he’s excellent on our issues.

———

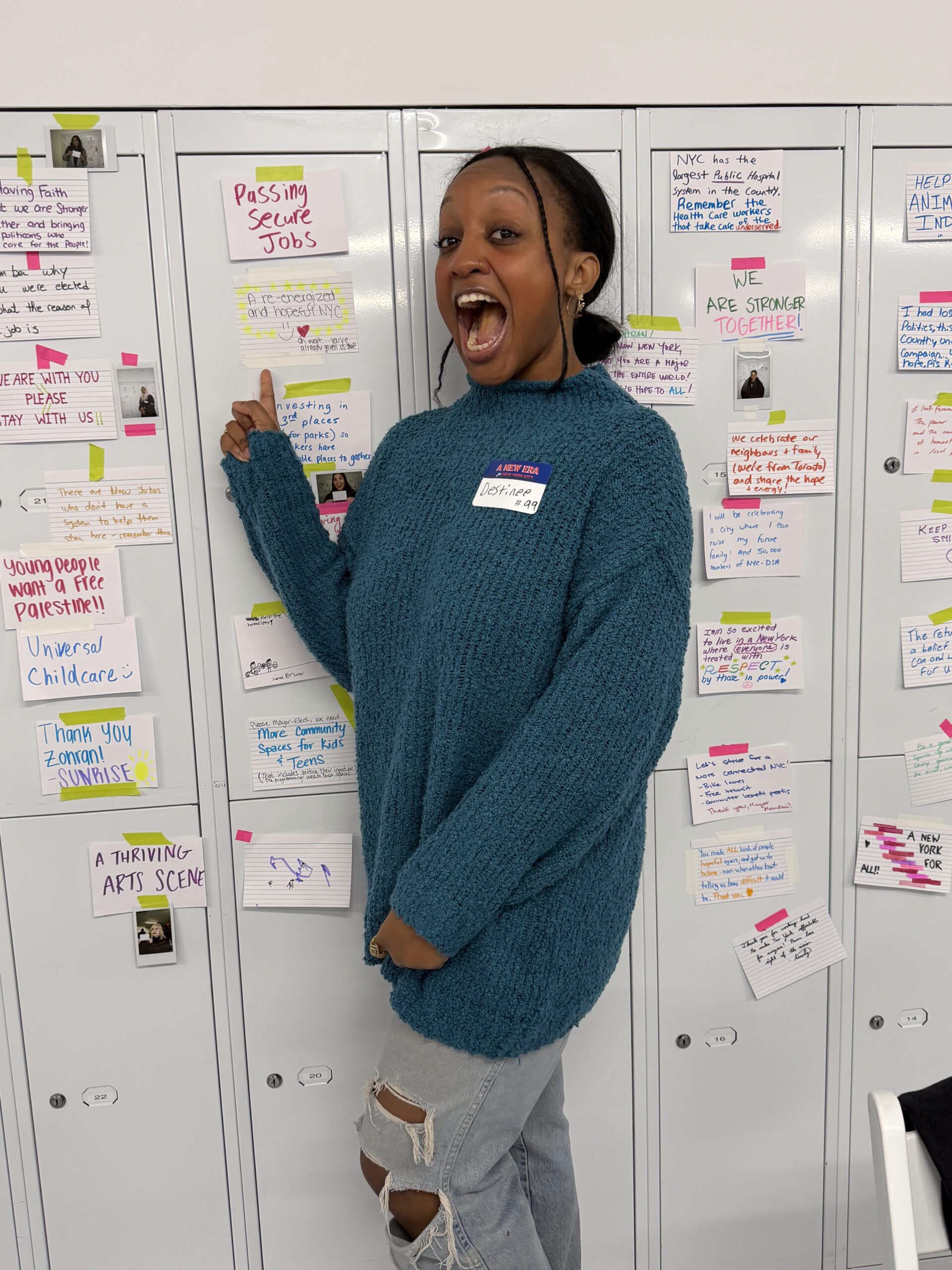

DESTINEE

OTTENBERG: What’s your name?

DESTINEE: Destinee.

OTTENBERG: What’s your neighborhood?

DESTINEE: Brooklyn, but Bed-Stuy specifically.

OTTENBERG: Oh, cool. What’s your New York story in a sentence or two?

DESTINEE: Oh my gosh. In a sentence or two? Well, I moved here at 17 by myself. I came for college, business school, but I’m an artist. For a long time, because of my own experience with the affordability crisis, I abandoned my artistry. But I was fortunate enough to find my way back to that through certain resources. Now I run a full-service entertainment firm that bridges the gap between the administrative side and the artistic side of the business.

OTTENBERG: What do you want to talk to Zohran about today?

DESTINEE: More structure and support and funding for independent artists. There’s only maybe four percent of us that are actually making enough money or have high enough stats to have access to resources that can really realize our vision and get us certain levels of visibility. That other 96% are really vulnerable to the dangers of this industry. There’s a lack of education and a lack of information.

Something that he ran on specifically was just the idea of being able to go for your dream. It may not work out exactly how you planned, but you should still have a roof over your head. And you should be able to try again or try something new. The other thing I want to talk to him about is servicing the queer community, which is another community I’m part of. We’ve been very appreciative of how vocal he’s been about his support for our community, especially the trans community. I’d like to know what that looks like concretely and whether he’s interested in engaging in some of the art forms coming out of that scene as well. It’s one of the biggest ways that we express ourselves. Where you see art, you usually see queer people.

OTTENBERG: What you’re saying is really interesting. I feel like there used to be amazing housing for artists.

DESTINEE: Totally. We did a video about this with an owner of a fashion brand. He was saying how his mom was able to take advantage of that housing as a working artist. She was able to make a living off of that, which gave him the opportunity to be able to pursue art full-time. And now he’s creating spaces for young and starving artists to have facilities to workshop our art, showcase our art, and have more access to resources. What he was posing to Zohran is, “What does that look like if it’s done across the board at an administrative level, as opposed to relying on individuals to create those spaces?”

OTTENBERG: And you will be bringing that up today?

DESTINEE: Yes.

OTTENBERG: Cool. Well, thanks, Destinee.

———

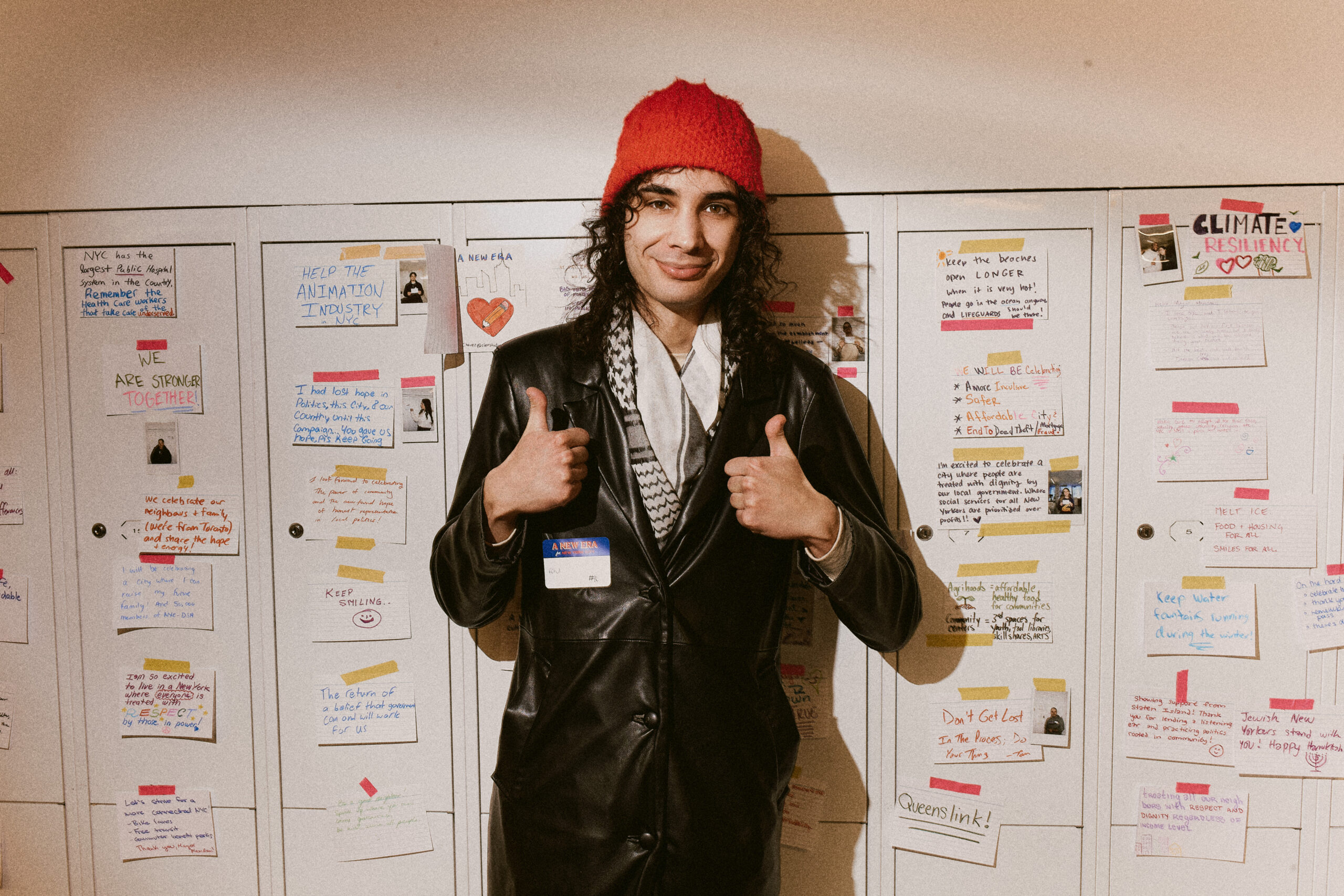

PAUL

OTTENBERG: What’s your name?

PAUL: Paul.

OTTENBERG: Hey, Paul. How are you doing? What neighborhood do you live in?

PAUL: Hi, I’m good. I live in West Harlem near Columbia right now.

OTTENBERG: Paul, what’s your New York story in a sentence or two?

PAUL: I moved here after college in 2021. I work in the arts, and so therefore I’ve really only been able to live in rent-stabilized housing to afford to live here and continue a career in the arts. I’ve been really thankful for that, but also afraid of further rent increases. That was part of what drew me out to volunteer for Zohran’s campaign, and I’m really glad that it paid off.

OTTENBERG: What are the issues you want to talk to Zohran about today?

PAUL: I plan to talk to Zohran about trans rights and standing up for trans New Yorkers. I also want to talk to Zohran about climate resiliency and resisting AIPAC and the Israel lobby’s influence on politics.

OTTENBERG: Cool. Do you mind if I get your picture?

PAUL: No, that’s okay!

———

EDWIN

OTTENBERG: Hey. What’s your name?

EDWIN: My name is Edwin.

OTTENBERG: And what neighborhood do you live in?

EDWIN: Washington Heights.

OTTENBERG: Tell me a little bit about your New York story.

EDWIN: Born and raised in New York. I’m 47. I went to school around the ’80s and ’90s public school in New York. I went to college in New York City as well.

OTTENBERG: Excellent.

EDWIN: It doesn’t get any more New York than that.

OTTENBERG: Yes, you’re extremely New York. What are the issues you talked to Zohran about today?

EDWIN: Specifically art in public education. It’s my priority and concern. Not only because I am an artist myself, but because art saved my life like it saved many in my community as well. But there’s been an intentional lack of funding towards the arts for about 30 years now. His mother comes from an arts background, and he himself tried it as well, and his wife. So I’m really hoping that his administration looks at the arts in public school through a different lens, other than just statistics and extracurricular programs.

OTTENBERG: You say that the arts saved your life. Were the arts funded differently in public school when you were going to school?

EDWIN: They were back then. I told him the story of when I was in elementary school, we got musical instruments that were given to us to take home. You don’t see that nowadays. Back then, it wasn’t just extracurricular programs. They were part of the program itself, meaning the academic program too. His administration could definitely pivot the shift on that.

OTTENBERG: What are you excited for in 2026, New York edition?

EDWIN: What am I looking forward to? I’m hopeful that the administration does name the right people as Commissioners, and as Deputy Mayors. I know there’s going to be some names that are from past administrations, because you need people with experience. But I do also hope for people who are creative and think outside of the box, understanding the real needs of New Yorkers on the ground. A lot of people live in certain communities and certain bubbles, and they don’t understand the reality of a mother in the South Bronx as opposed to one on the Upper East Side. They’re in the same city, but there are a lot of differences and there are a lot of needs to be addressed.

OTTENBERG: Okay, cool. Thank you, Edwin.

———

GAYLE

OTTENBERG: Gayle, how are you doing?

GAYLE: I’m doing good, thank you.

OTTENBERG: Where do you live?

GAYLE: I live in the North Bronx.

OTTENBERG: What’s your New York story, Gayle?

GAYLE: I’ve lived in New York since 1996. I lived in the West Village for 10 years, and now I own a home in the Bronx. I’m raising a teenager there right now.

OTTENBERG: Nice. What were the main things that you wanted to talk to Zohran about today?

GAYLE: I’m not here for my job, but I talked to Zohran about my job with Citymeals on Wheels, and taking care of older adults and their hunger needs.

OTTENBERG: That must be a lot more difficult to take care of everyone right now because of how expensive everything is.

GAYLE: Yeah, affordability hits older adults too. He’s our affordability mayor, right?

OTTENBERG: Right. And how did it go?

GAYLE: I think it went well. He listened and he took notes, and that’s what I wanted. I wanted to make sure that I was heard. I also talked to his Chief of Staff and she said, “I hear you. You are heard.” You might not get everything you want, but it’s great even if you just know that you got that message across and that you’ve been heard. And what I’m seeing them doing a lot of today is listening to people. I’m in my late 50s and I have never seen anything like this from an elected official, where they’re doing an open call to any New Yorker like, “Come and talk to me.” That is really emotional for me. That’s the highlight of my day today.

OTTENBERG: Oh, same. It’s actually choked me up multiple times today.

GAYLE: That was the last thing I talked to him about. I said, “I’ve never seen anything like this.” And then I put my hand to my chest and he put his to his chest and it was nice.

OTTENBERG: Beautiful.

———

BRYANT

OTTENBERG: Hey Bryant, how are you doing?

BRYANT: Good. How are you?

OTTENBERG: I’m good. What’s up?

BRYANT: Still coming down from the high of talking to Zohran. I mean, that was great. In three minutes you can squeeze a lot in, but I thought we had a really good conversation. I really wanted to talk to him about a more connected New York City. I live here in Astoria. There’s a lot more bike lanes, I guess, than there used to be. But on the outskirts of New York City, where I’m originally from in Ozone Park, you don’t really see that. You don’t see a lot of the Citi Bikes, you don’t see a lot of those bike lanes. You can get connected more closely through bikes. You don’t need to take that five minute Uber ride.

OTTENBERG: We desperately need more connection.

BRYANT: Yeah.

OTTENBERG: What was Zohran’s vibe?

BRYANT: He was very receptive to that. He seemed to be really open to it. He lives here in Astoria, so he kind of saw that same thing. He does ride his bike around, so he’s felt it firsthand.

OTTENBERG: Have you ever got in an accident?

BRYANT: No, thank god. I would’ve normally rode my bike here today. I didn’t because the streets weren’t paved from the snow. I didn’t want to get into an accident either from drivers or from just me being on a bike.

OTTENBERG: When I was in my 20s—this is before bike lanes and Citi Bike and everything—I was such a crazy biker and I really thought I was invincible. So now I’m terrified. I won’t get on a bike. But it’s for the young.

BRYANT: Yeah, exactly. I am wearing my helmet, but I know a lot of people don’t.

OTTENBERG: Cool, cool, cool. What neighborhood do you live in?

BRYANT: In Astoria.

OTTENBERG: Well, thanks Bryant.

BRYANT: Yeah, thank you.

———