Bianca Censori is staring into my eyes, deeply. Her big brown saucers are slow-blinking like a cat’s. This is a sit down interview, a followup to BIO POP, her debut performance in Seoul, but the artist in latex isn’t answering my questions—not directly at least. Instead, a young, dark-haired woman muffled by a plastic Bianca-inspired mask is speaking for her, and I, “the media,” am part of the performance.

Censori is known to the masses as Ye’s stunning second wife, a Kardashian look-a-like with a penchant for public nudity. I prefer to think of her as a cunning provocateur, a performance artist who’s turned TMZ into her own personal museum with a series of controversial stunts (remember that time she wore a pillow as an outfit?) But it wasn’t until the 2025 Grammy’s, when the Australian artist dropped her fur coat on the red carpet to reveal a dress so sheer it was almost non-existent, that she really made her mark. This was full-on indecent exposure, a move that had moms across the midwest frantically Facebooking their rage. But it was also an artistic statement made by a public figure who’d spent the last several years being stalked by paparazzi, as if to say, “You want a piece of me? Take it all.”

Of course, not everyone is so convinced by Bianca’s public performances. The tabloids have deemed her a puppet, a silent character in Ye’s incessant attention-seeking act. And while it’s true that Bianca’s platform is in part thanks to her husband’s rabid haters and stans (some of whom I fought for a front row position during her performance in Seoul), I had no doubt that this was her moment, an opportunity for the 30-year-old artist and architectural designer to show the world that she’s more than a mannequin—or at least a mannequin who designs her own window displays.

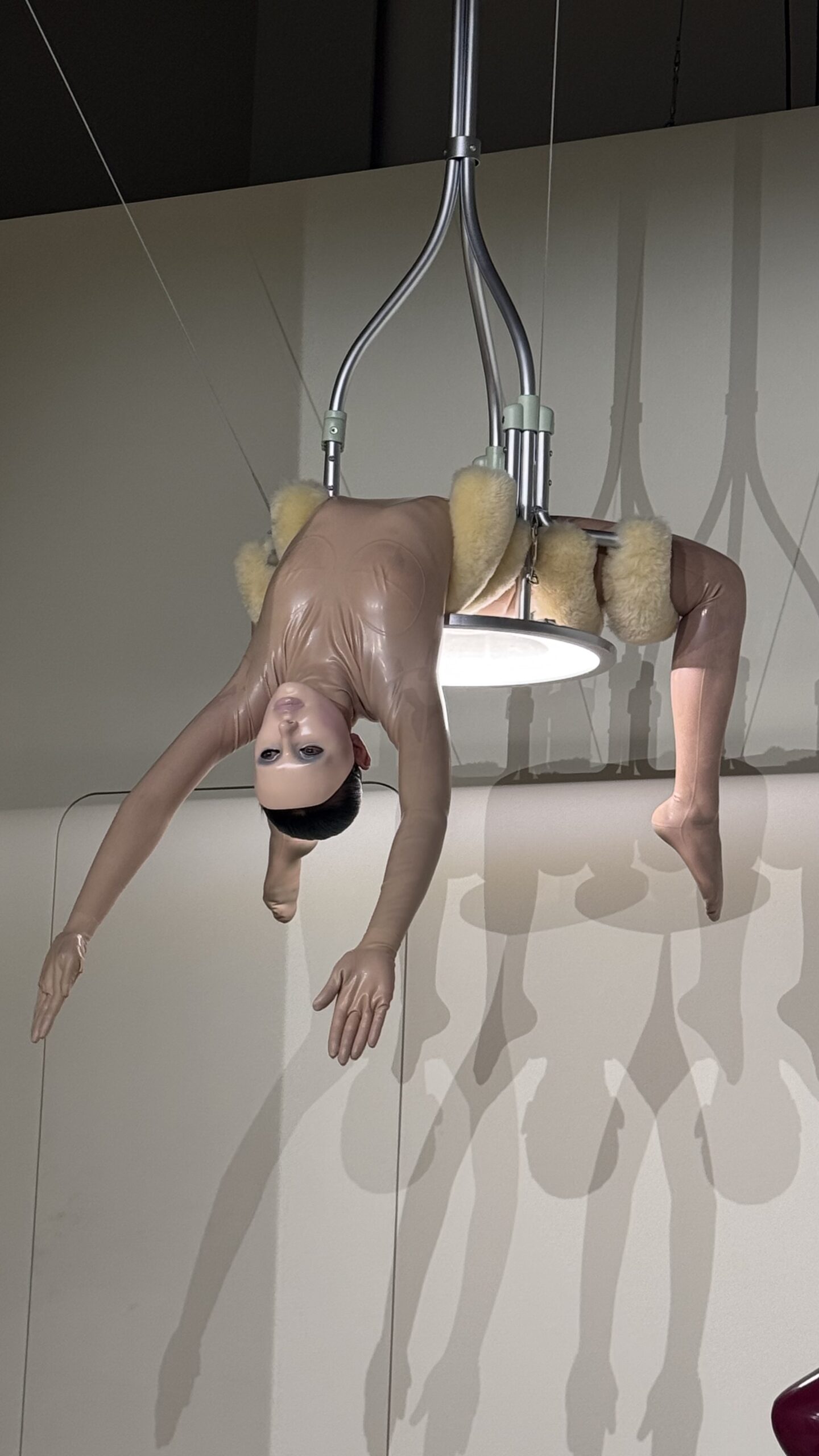

BIO POP begins with Bianca methodically mixing up a concoction in a stainless steel approximation of a kitchen. She appears, bot-like, repetitive, a stoic Barbarella in a dark red latex suit. Her mission? To serve up a gelatinous, bloody cake to a room full of clones constrained by surgical-inspired furnishings. The obvious comparison is Allen Jones’ “female furniture,” only Censori’s women, (one of whom is a contortionist from Kansas City), and the objects they fit into, can stand alone.

In BIO POP, objectification is both physical and metaphorical, a feminist statement as old as the Space Age references prominently featured throughout. According to comments on a viral post of the performance, those in the art world found the messaging a little redundant, while others found it “horrifying,” “retarted,” and “an extremely disgusting display of women.” But in person, at least through my eyes, the show was best described as captivating, rebellious, and kind of hot. Here’s a woman the media has deemed submissive, stupid, slutty even, flipping the script on her own terms. You want to dissect Bianca’s image? Her body? Her essence? Here she is, domestic, yet dominant, as if to say, “You can put a woman back in the kitchen, but you can’t take away her sexuality, her agency, her power.”

Staring back into Bianca’s big brown eyes while her doppelganger drones on, I can feel both her strength and vulnerability. “This is an act of repossession,” the doppelganger tells me. “So why not speak?” I reply with my eyes. The interview ends and a smile beams across Bianca’s face. “Thank you so much,” she says, embracing me. The performance is over. We’re just two women again. Three if you count her mini-me.

—

TAYLORE SCARABELLI: You’ve been performing in public for a few years now. Why is performing and presenting physical work in a more institutional setting important for you?

BIANCA2: Bianca has always been a visual artist. The work has been happening for years. It’s just being presented formally now. Art takes time.

SCARABELLI: What is the significance of your doppelgangers? Do you ever feel trapped in your own image?

BIANCA2: The doppelgangers are not copies of Bianca. They’re spillages. They’re what happen when a public image detaches from the person who animates it.

A woman in the public eye is forced to watch versions of herself multiply without her consent. People project, people invent, people erase. So she sculpts the versions they create, the phantom selves.

This is not a confession of feeling trapped. This is an act of repossession. She is reclaiming the unauthorized clones. She’s not trapped in her image. She’s multiplying it until the original becomes myth.

SCARABELLI: You’ve created a lot of controversy with your provocative personal style. With this performance of domesticity, are you enacting what the public wants from you, to perform the role of a wife and domestic worker, instead of that of a liberated woman?

BIANCA2: Bianca is interested in perspective and collective experience. Domesticity is one of them.

SCARABELLI: Immediately after the show, people on social media were outraged by your nod to Allen Jones’ sculptures of women as furniture. Why is that work significant to you? And why do you think people have such a hard time consuming works of art that highlight the subjugation of women today, over 50 years after you first created those objects?

BIANCA2: Allen Jones is an obvious reference, but he’s not the only one. The work is intentionally referential. For a first chapter, it needed to be.

SCARABELLI: How much does sexuality, yours and others’, factor into your work? Is the female body inherently sexual?

BIANCA2: Sexuality is incidental. It’s not the point. The female body isn’t inherently sexual. That’s a cultural overlay.

SCARABELLI: This work is quite provocative, especially for Korea. Why did you choose to show in Seoul?

BIANCA2: Because Korea understands ritual, performance, and symbolism as a part of daily life. The audience there is visually literate and willing to engage without needing moral framing.

SCARABELLI: Can you tell me about your choice to wear a bodysuit? In which ways are you repudiating and/or celebrating fetish culture? Are you referencing any particular iconography with this look?

BIANCA2: The body suit is the closest thing to skin. It removes individuality and turns the body into a surface. What people read into that fetish, control, power, belongs to them.

SCARABELLI: How does the media influence your work? Are you anticipating backlash? Do you love it? What’s your end goal?

BIANCA2: Bianca views social media neutrally, not as something she’s emotionally invested in, but as a space where perception mutates quickly and publicly. She doesn’t seek praise or backlash, but she pays attention to how both form and circulate. They’re two sides of the same perceptual mechanism, and the contrast between them is useful.

Backlash isn’t a goal, but it is revealing. It shows where cultural sensitivities sit and what people are unable or unwilling to name directly. Bianca’s end goal is self-expression.

SCARABELLI: I’m going to ask you a couple of rapid-fire questions now. What’s your purpose?

BIANCA2: Expression.

SCARABELLI: Who influences you?

BIANCA2: Reality.

SCARABELLI: How do you define being?

BIANCA2: Tension.

SCARABELLI: Where do women belong?

BIANCA2: Everywhere.

SCARABELLI: Do you cook?

BIANCA2: All the time.

SCARABELLI: What keeps you sane?

BIANCA2: Making.

SCARABELLI: What do you believe in?

BIANCA2: Instinct.

SCARABELLI: What’s your fetish?

BIANCA2: Precision.

SCARABELLI: What do you make?

BIANCA2: Structures.

SCARABELLI: Who do you want to look like?

BIANCA2: Myself.

SCARABELLI: What do you want to prove?

BIANCA2: Nothing.

SCARABELLI: How do you control the narrative?

BIANCA2: Silence.

SCARABELLI: Why now?

BIANCA2: It’s time.