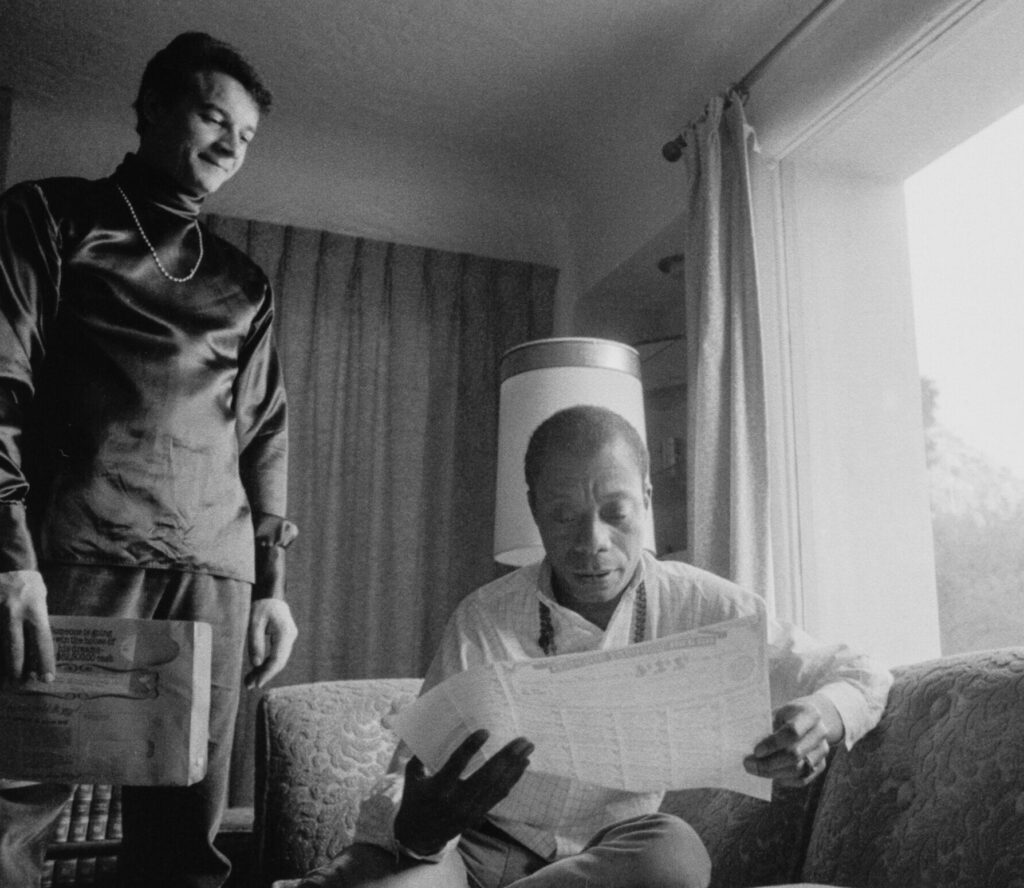

Alain and James Baldwin in Los Angeles, 1969. (© Sedat Pakay)

The first time Nicholas Boggs and Richie Shazam chatted about James Baldwin was at a Chinese restaurant in Chelsea over 20 years ago. Boggs recalls identifying a certain something in Shazam—“a sense of destiny,” as he puts it—that reminded him of the acclaimed author of Giovanni’s Room, Another Country, and several of the most stirring stories and essays of the 20th Century. It marked a full-circle moment, then, that Boggs and Shazam reunited earlier this month to revisit the subject of Baldwin once more. This time, the occasion was Boggs’ new book Baldwin: A Love Story, a comprehensive, 700-plus page tome exploring the relationships, both romantic and platonic, that shaped Baldwin’s life and work. “Everybody talks about how much they love Baldwin, how love is such a big part of both his fiction and his nonfiction,” explains Boggs, whose inquiries into the subject began as early as the late 1990s. “But his life has never really been told through these loves.” His research, as he told Shazam on a Zoom call, illuminated several of Baldwin’s most formative and underappreciated relationships, including his whirlwind romance with the French painter Yoran Cazac and a mostly unrequited longing for the Turkish actor Engin Cezzar, among others. As Shazam said: “There’s a lot to unpack.” Below, he and Boggs go deep on the power of chosen families, Baldwin’s legacy, and how he might regard America’s troubled state of affairs if he were alive today.

———

RICHIE SHAZAM: How’s it going, babes?

NICHOLAS BOGGS: It’s so good to see you. The last time I saw you I think was when your book came out.

SHAZAM: Oh my god, that’s really crazy. It feels like ages ago. I don’t know what it is, but as I am getting older and understanding the quickness of time—

BOGGS: I think I joked with you when I saw you. I said, “Richie, when we met, I was working on this book, and here you are finishing a book way before me. How could you do that to me?”

SHAZAM: Well, that also has to do with the feat at hand. Congratulations on fulfilling this incredible fantasy and turning it into this reality of almost 600 pages of blood, sweat, and tears. You’ve been on an odyssey making this come to life and I’m so grateful to have this moment to just talk about all things in relation to this incredible work.

BOGGS: Thank you. I think we first talked about Baldwin at a Chinese restaurant in Chelsea many decades ago. We won’t say exactly how long ago, but I remember you as a young, incredible person. You weren’t yet Richie Shazam, the legend, but I actually talked about how there were certain similarities between you two, growing up queer people of color in New York City and making your way from a loving but complicated family situation into the world and having a sense of destiny for yourself. I remember that about you, and Baldwin had that too. He had these recurrent dreams of becoming a famous writer and driving a fancy car and helping his family. There was something similar going on with you.

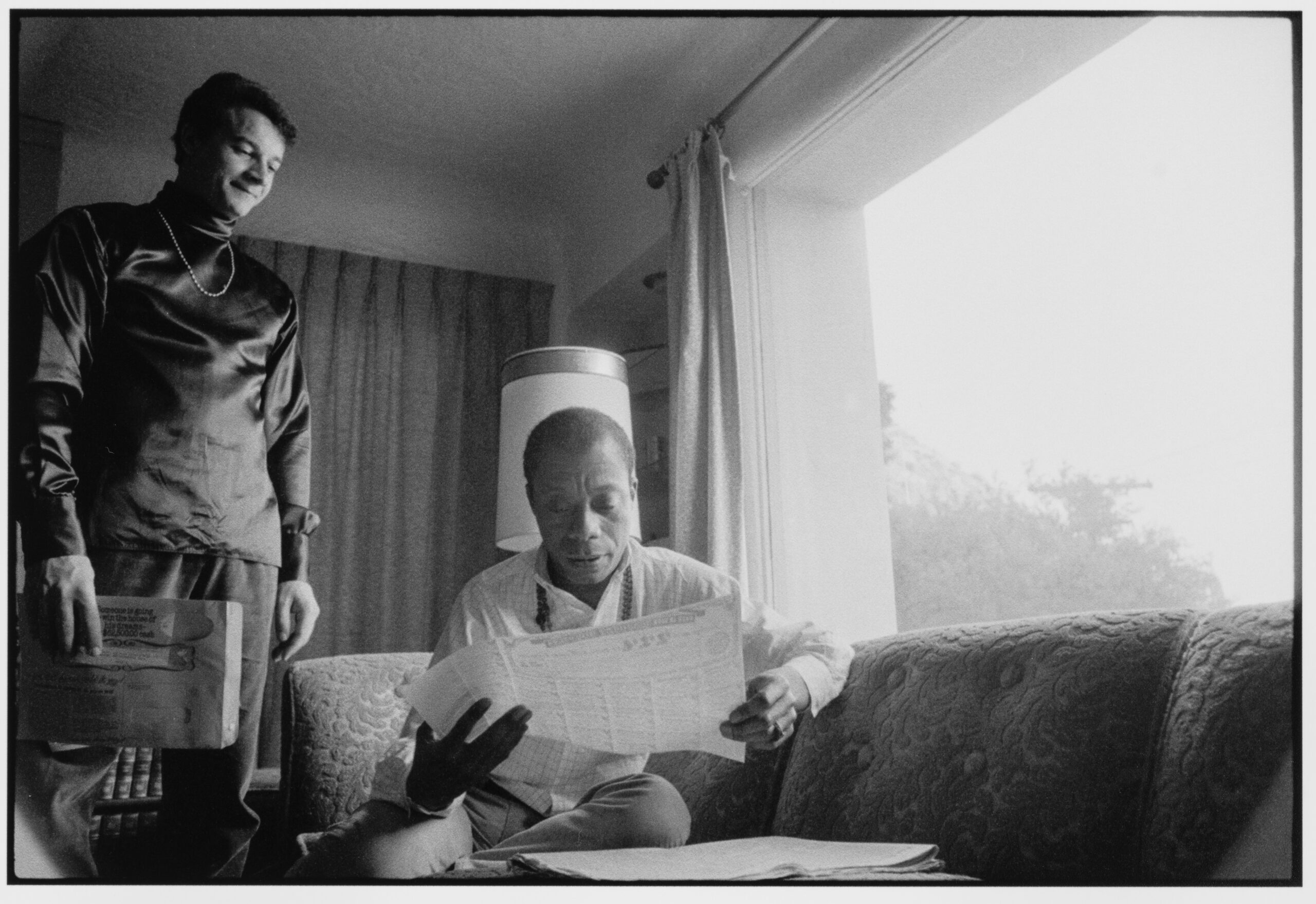

James Baldwin with the civil rights activist Jerome Smith outside the ANTA Theatre on Broadway in 1964. (Photograph by Bob Adelman)

SHAZAM: Yeah, I feel this weird torturedness to the text and everything that you encapsulated about Baldwin’s personhood, his individuality. And I too have felt the sense of wanting to escape what I know, to escape America. Growing up in Queens, I grew up with access to so many different cultures and languages and bits and blobs of the world while actually needing to separate myself and understand America more from being outside. That was something that resonated with me. There’s just so much to take in and it’s not something that you casually gloss over. No, there’s a lot to unpack.

BOGGS: Well, to follow up on your point about New York and going abroad, it was so important to Baldwin as an artist and a thinker as I think it has been to you. He actually kind of hated New York whenever he came back—it just drove him crazy and he really had to live elsewhere. And this began for me through one of his “Elsewhere” stories. I was in college and I discovered this out-of-print children’s book by Baldwin that he had published in 1976. And the second email I ever sent in my life was to Baldwin’s personal assistant and also early biographer, the wonderful David Leeming. I wrote, “Do you know anything about Yoran Cazac, this mysterious illustrator?” You could kind of tell from reading between the lines of Leeming’s biography that Baldwin had probably been lovers with him, but he was married and had a child and Baldwin was the godfather to this kid. So David Leeming wrote me back a really nice email saying, “I never met Yoran Cazac. I don’t know anybody who’s still alive who did and I think he’s dead.” So I kind of gave up, but then seven years later, I moved to New York. I sent some more emails out to art historians in Paris saying, “Do you know anything about this obscure deceased French painter, Yoran Cazac?”

A few weeks later, the phone rings in my studio apartment in Brooklyn. It’s Yoran Cazac, in this raspy French accented voice, saying, “I’m alive, I’m in Paris, I’m having an art exhibition, come over.” So that was way back in 2003. And then I uncovered the fact that they had not just been collaborators. Baldwin dedicated If Beale Street Could Talk to him. They had also been lovers. And what I realized in that process was that everybody talks about how much they love Baldwin, how love is such a big part of both his fiction and his nonfiction, but his life had never really been told through these loves. So it set me off on this long odyssey that’s been going on for almost three decades that culminates in this book where I explore four of these great loves. And, through the prism of love, I try to tell his whole life story.

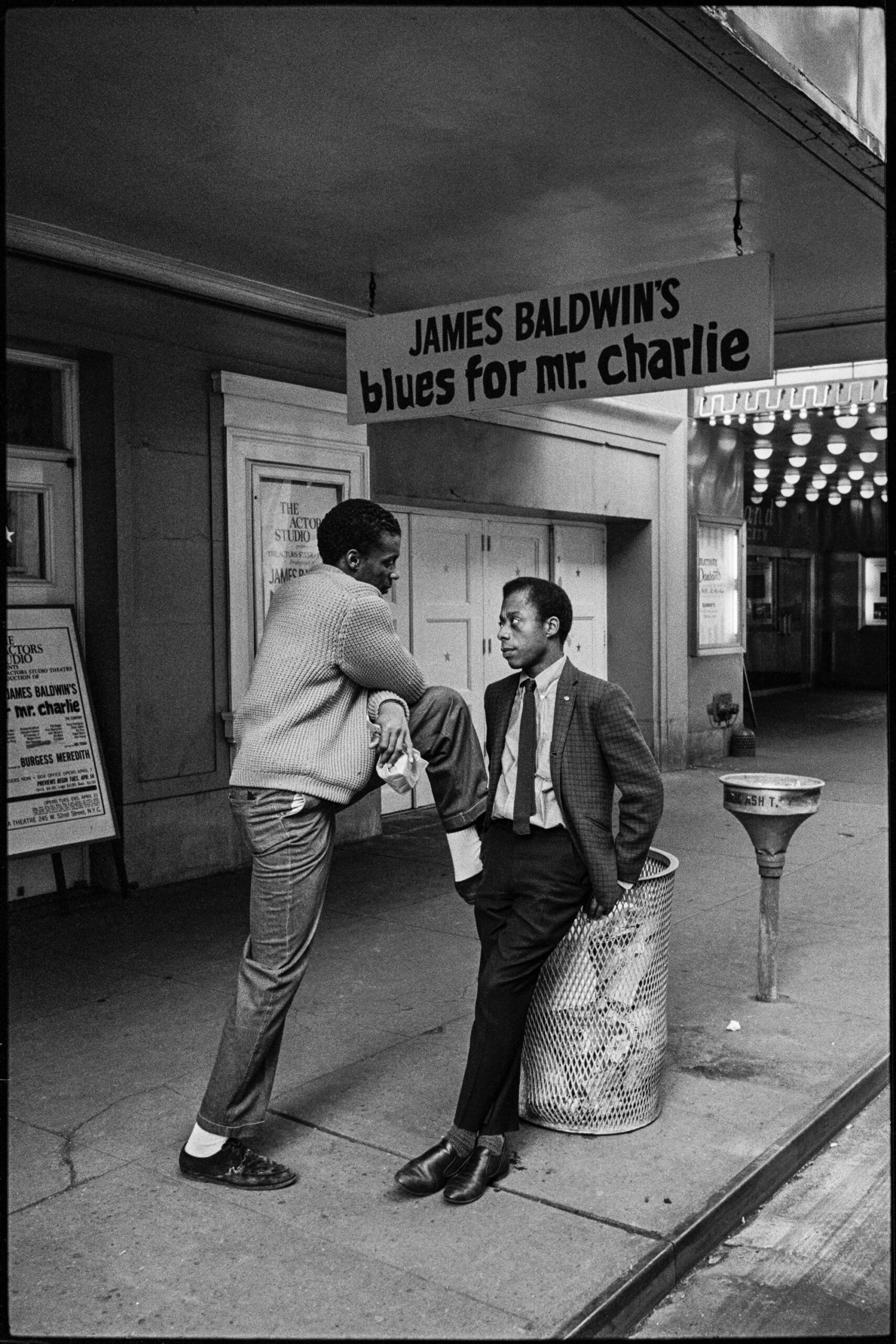

Blinky, by Yoran Cazac, in Little Man, Little Man. © Yoran Cazac [Beatrice Cazac]

SHAZAM: It’s beyond. What fascinates me is the dimensionality of these lovers and just imagining him being so tortured. “I love this person, but they can’t commit.”

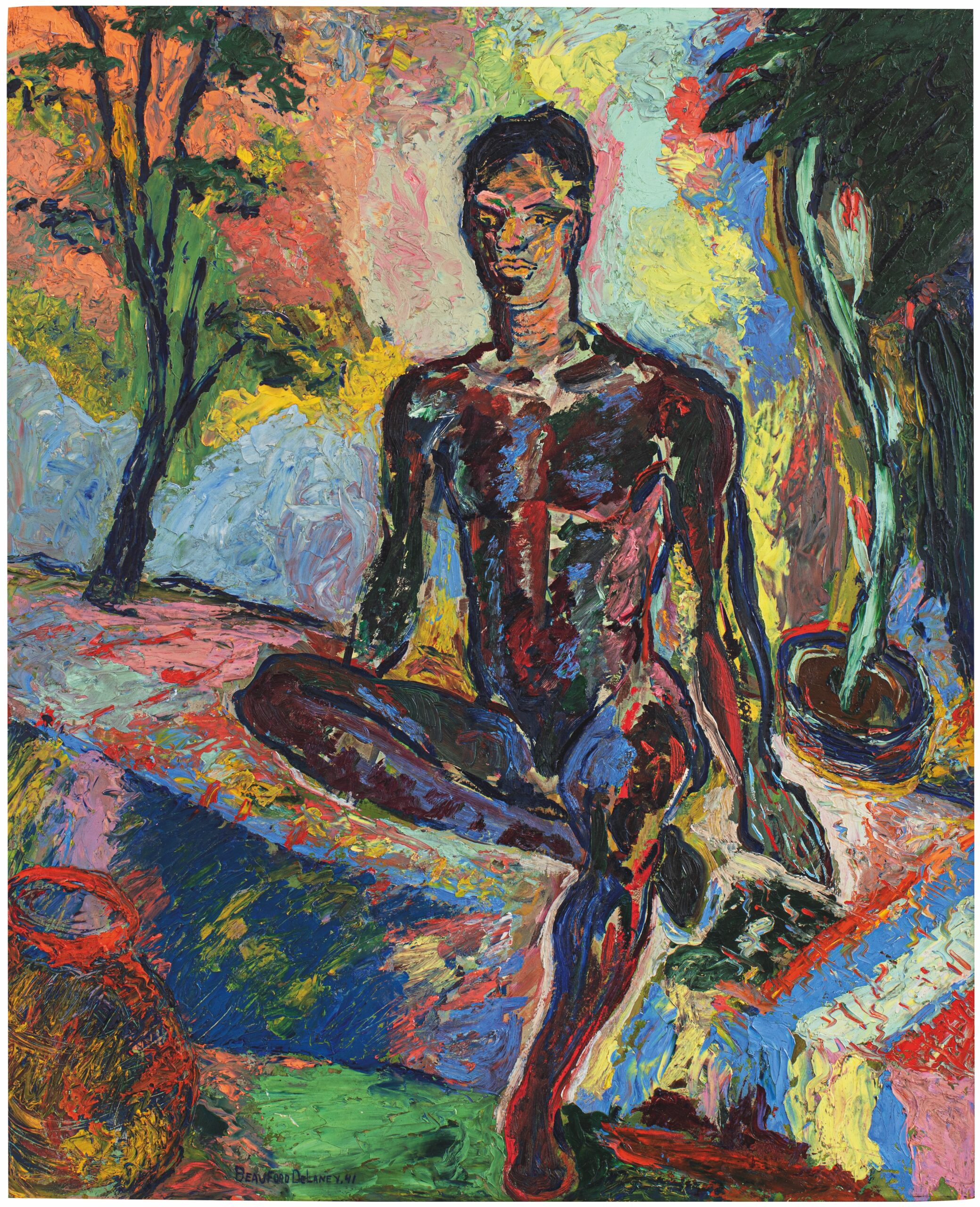

BOGGS: The way that he constructed these alternative families, these chosen families— I mean, you have done that in New York and elsewhere. He loved his family in Harlem, but he was living abroad, so he had to construct these alternative families with people like Yoran Cazac, the painter Beauford Delaney, with Mary Painter, even with Toni Morrison, Lorraine Hansberry, Nina Simone. He created this alternative family of artists and civil rights activists and really modeled how it’s possible to create communities of care and thought and survival. There’s all kinds of different loves that queer life can experience, which is something beautiful about the life that you’ve constructed.

Beauford Delaney, Dark Rapture (James Baldwin), 1941. Oil on Masonite, 34 x 28 inches. (Collection of halley k. harrisburg and Michael Rosenfeld, New York). © Estate of Beauford Delaney; Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

SHAZAM: I really appreciate that. And with everything that’s happening in our country, in our world, even in our city, I too feel this strained relationship with New York. So I do contribute a lot of my ability to persevere and push through to these families of my own construction. We just want to break free of the boxes, to be accepted and loved for who we are. It’s like, “How do we make peace with this tortured existence?”

BOGGS: Baldwin wrote about that in one of his final essays: “Here Be Dragons” for Playboy. This was 1986, I think, and he was writing about androgyny and already thinking about the kinds of trans identities and trans issues that are so present with us now. He wrote that each of us contains the other— male and female, female and male, black and white, white and black—nd he was really on the vanguard. And it’s really interesting that later in his life he was really starting to understand himself as androgynous. He was starting to write his novels from the first-person perspective of a woman, a Black woman, in If Beale Street Could Talk. I wish that he were alive today to intervene in a way that Americans could hopefully understand more than some of them seem to. But I wanted to ask you if you had a chance to look at the color inserts in the book because, first of all, you’re a photographer and I’m such a fan of your photography. The first one is Richard Avedon’s photo of Baldwin.

SHAZAM: Wow.

BOGGS: Iconic.

SHAZAM: His eyes are just so piercing. It feels like they sting you. You feel this stinging presence.

Richard Avedon and James Baldwin, Harlem, New York, October 15, 1946.

BOGGS: I’m actually down in Washington, DC right now for a book event, and this is where I was born and raised. And the first time I saw Baldwin’s face, it was a drawing of him in my eighth grade English class in the DC public schools. That was my first encounter with James Baldwin and I just remember how amazing his eyes were.

SHAZAM: When he smiles, he radiates so much. It’s so much joy to be in the moment. And I feel like if we theorized about what it would be like if he were here today, I think he would feel our shared exhaustion. I feel like he would just be really tired.

BOGGS: When he was in junior high school, his quote under his yearbook picture was, “Fame is the spur. And ouch.” He really, really, really wanted to be famous. And then when he became famous, he really felt menaced by it. That’s why he had to leave for Istanbul, where he lived for most of the ’60s. Have you been to Istanbul yet?

SHAZAM: I actually went to Istanbul when my mother passed away in high school. I went for three weeks and—

BOGGS: No way.

SHAZAM: It was incredible. I actually have been having weird pangs inside about going back.

BOGGS: Let’s go together.

SHAZAM: I would love to. I feel this strong desire. Also, wasn’t he attacked in Turkey?

BOGGS: He was attacked in Erdek, yes. By a weird magician, and that was just one example of him being attacked for his racial and sexual “otherness.” But he also directed a play in Turkey. He directed Fortune and Men’s Eyes in Turkish. It’s a gay prison play and the guards and everybody dressed up in drag for Christmas.

SHAZAM: Wow.

BOGGS: It was this incredible moment where he kind of broke out of all these conventions. That’s where he finished Another Country. It’s where he wrote The Fire Next Time. But anyway, he directed this play and he kind of fell in love with this beautiful Turkish actor, Engin Cezzar. But they became “blood brothers” instead, as he put it. So that’s another example of creating these other kinship structures out of desire that maybe wasn’t realized but became something else. I did a couple research trips to Istanbul, actually, and I fell in love with it. And my research assistant for the book is Turkish. It’s such an important place and I just love knowing you were there.

SHAZAM: Yeah. And right now, with these very intense shifts to traditionalism and conservatism happening globally and in America, we need to be strongly bombarded with these histories—and especially with the erasure of our history. I just need something new and fresh. It’s about community building and connecting with people in real spaces.

James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin at the press conference announcing the National Day of Mourning, 1963. (Photograph by AP Photo)

BOGGS: It does feel like we’re in an emergency situation now. It’s not the same kind, but it really has that feeling. Baldwin called it the “welcome table.” He had a house in the south of France, and this is where Nina Simone and Marlon Brando and Josephine Baker would come. And normal folk, too, friends of his who were passing through. And they would come together to find joy, to find connection, to talk about politics but also just to support and sustain each other. Because I think as artists, as writers, as culture-makers and just as people, we really need each other now.

SHAZAM: Even if it feels hard to connect with people right now, it’s a necessary challenge. And with the pandemic—I’m excited for those studies 15 to 20 years from now to see how they’ll talk about it. I feel like a lot of people are acting like it didn’t happen, but there were some very damning effects. And I think a big one is socializing with others and how we choose to connect.

BOGGS: You sound like you’re jaded, Richie, but I’m excited for whatever you do next. Because I will never forget sitting in that Chinese restaurant and saying to you—you already knew this—but I was like, “Richie, you are a star. It’s going to happen soon.” And you were very humble about it, but I knew it and I think a lot of people knew it. And I’m so proud of you, just having watched your whole journey.

SHAZAM: I’m so beyond proud of you as well. The gag is that I’m not ever jaded, because I’m always working on a bunch of things at once.

BOGGS: Good. It sounded like you were jaded there, just for a second.

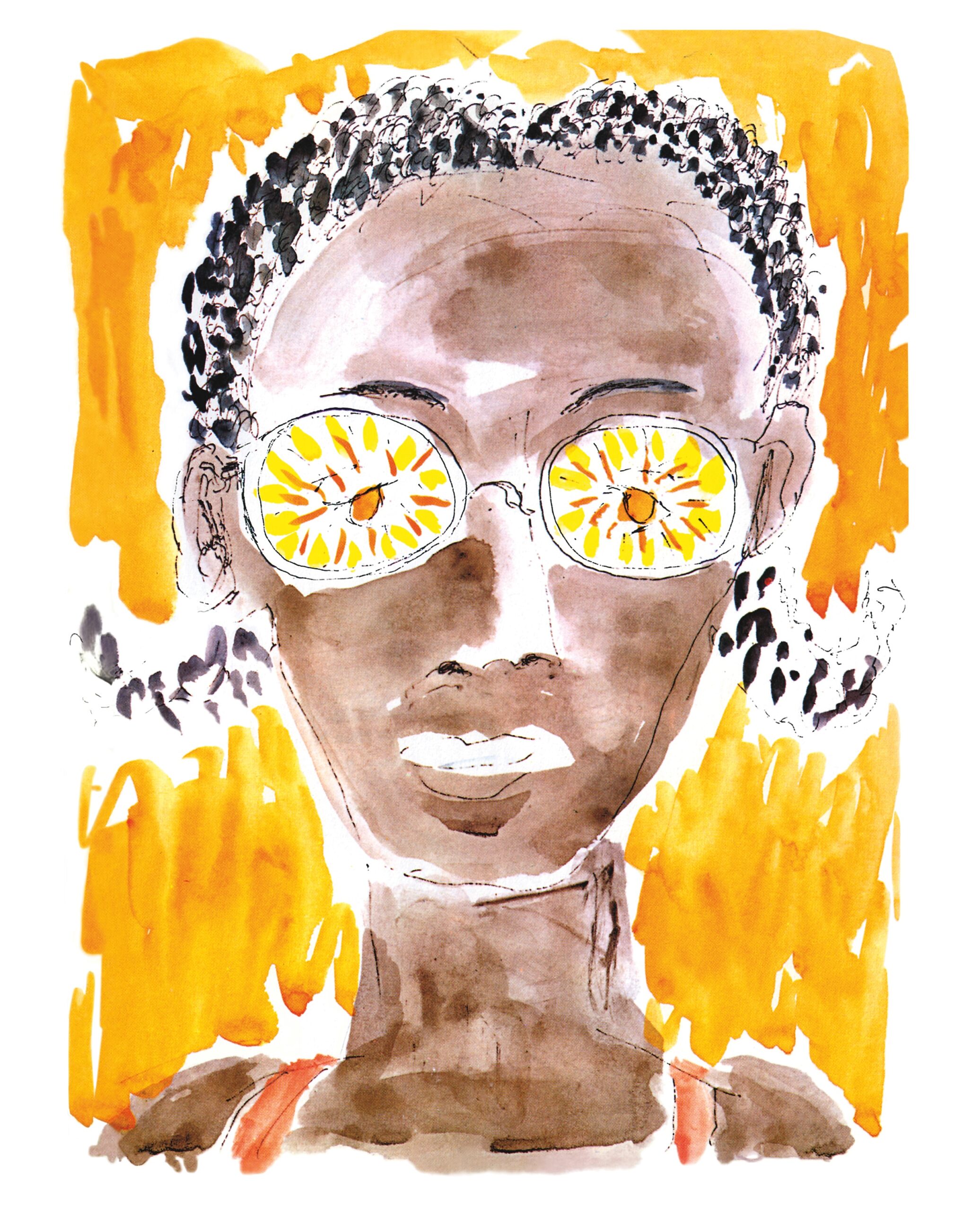

James Baldwin with Diana Sands and Burgess Meredith, opening night of Blues for Mister Charlie, 1964. (Photograph by AP Photo/Matty Zimmerman)

SHAZAM: When I just take a beat to listen to the voices in my head, that’s usually when I get so exhausted. I’ve always just appreciated the hustle, but my priority is doing things with my friends. I always say yes to engagements with my friends because I just know that it will feel like a safe, protective shield blanket covering me. But also, I just want to know if you could just leave us with any tidbits or anecdotes about the process of making this book. I know there was travel, there were all the residencies. But what’s something that we don’t know that happened?

BOGGS: So, as you know, Baldwin actually attempted suicide multiple times in his life. He had these big ups and downs, and one of the times was in Corsica, where I got the Robert Caro Fellowship. I took my mother with me to Corsica and we found the house, thanks to my mom. We went down to the town hall and we found the address of the house where he had stayed, where no Baldwin biographer had ever visited it. So we go there and it’s July, it’s hot as hell, we knock on the door and nobody answers. We’re walking down towards the water because Baldwin had walked down to the water where he considered drowning himself. So anyway, we’re walking down towards the water and we look back and on that terrace and a woman is doing her laundry. So what do I do? The intrepid biographer that I am, I jump behind a bush. But my mother goes bonjour, so up we go into the house, which was the same as it had been when Baldwin stayed there. We heard all the stories about the house, its construction, how it looked then. Bob Caro wrote a book called Working and it says, “When you’re a biographer, you have to turn every page and you have to go to every place.” And I said, “There’s one more rule for biographers—always bring your mother.”

SHAZAM: That is so kooky. I’m living for that. I just saw it all flash before my eyes.

BOGGS: I can’t wait to see you again, Richie. You know I’m obsessed with you.

SHAZAM: I missed you.

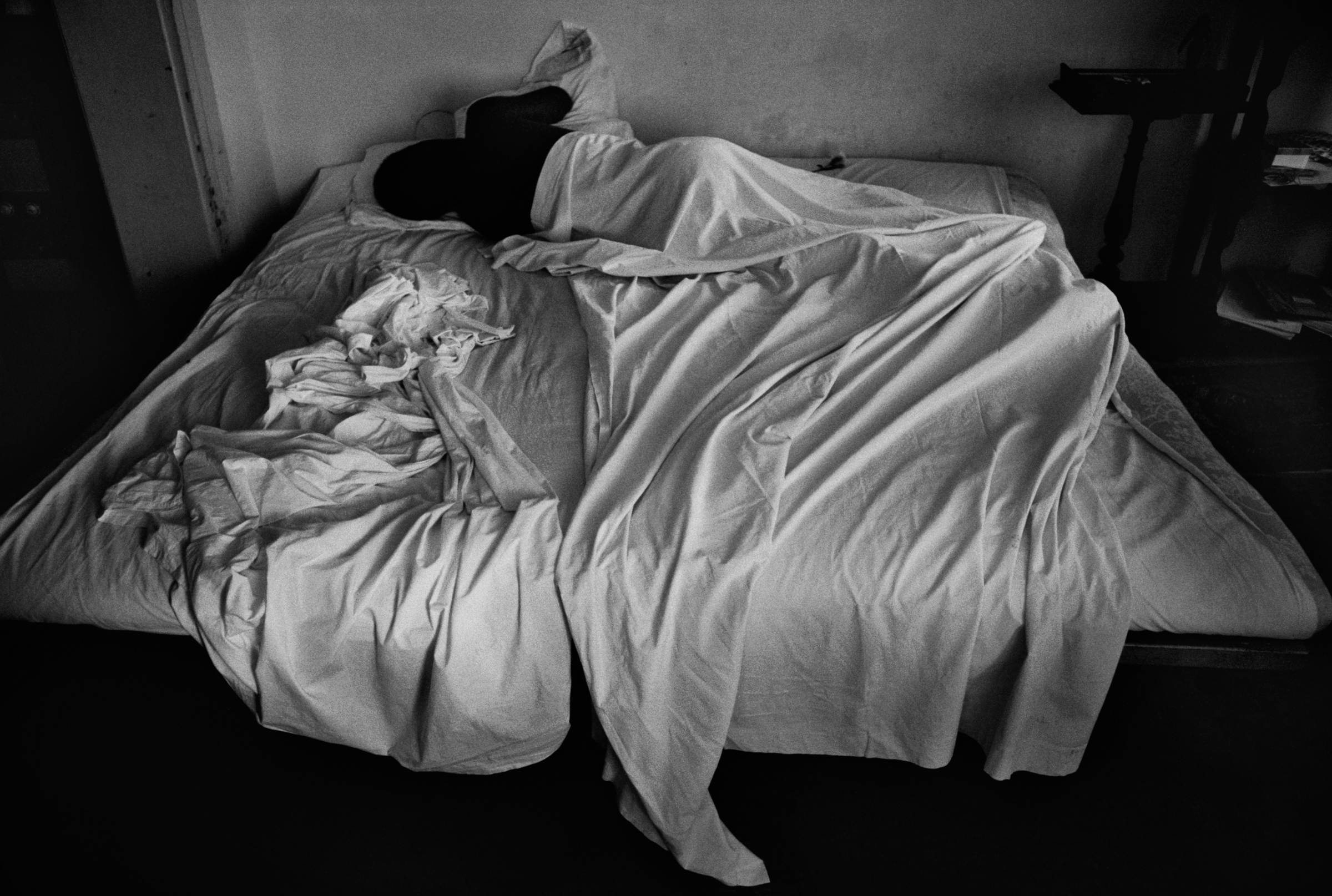

James Baldwin in bed, Istanbul, summer 1966. (© Sedat Pakay)