One day after that request, an unsealed, four-count federal indictment formally charged Mangione with—among other charges—murder through the use of a firearm, an offense punishable by death. And a week later, on April 24, just as Mangione was expected to appear in federal court for his arraignment on this new set of charges, the Justice Department, through the US Attorney’s Office in Manhattan, filed—finally and formally—its death notice.

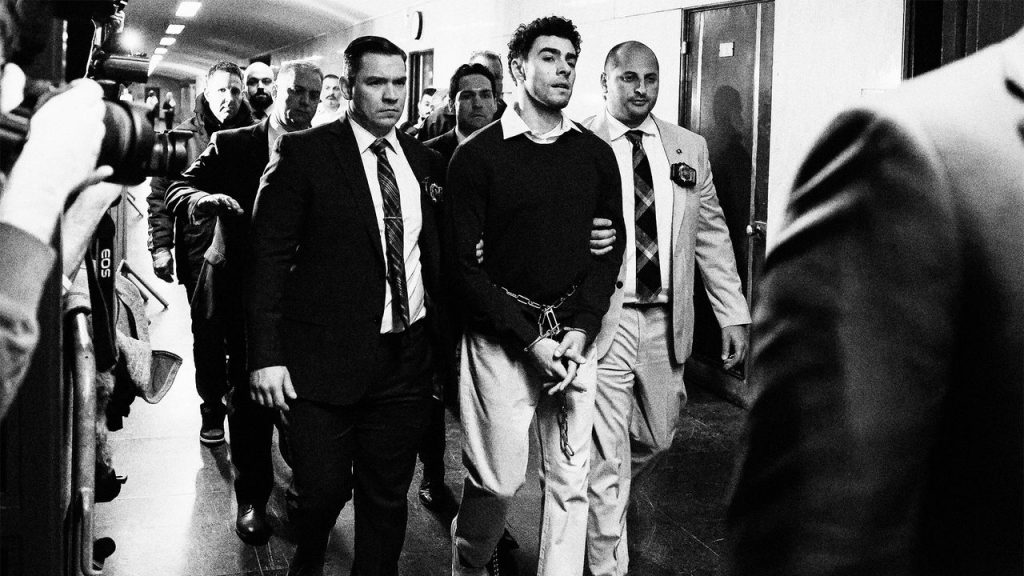

During his highly publicized federal court appearance on April 25, Mangione, as a matter of course, pleaded not guilty. But the judge left the door open for his lawyers to once again raise the issue of “any pre-indictment conduct by the government”—and the suggestion that Bondi’s intent to seek the death penalty be rejected outright.

“In other words,” as US district judge Margaret Garnett said in open court, she would like to entertain “arguments directly going to whether I should preclude the government from seeking the possibility of capital punishment as a punishment in this case.”

Bondi’s Justice Department’s aggressive pursuit of the death penalty, with an apparent lack of regard for the established rules and processes that come with it, has been facing pushback from a number of federal judges. As of August 22, according to the Associated Press, her agency has sought the death penalty against 19 people.

One major stumbling block in this campaign has been the department’s attempts to reorient cases filed or set in motion during the prior administration, as it has with Mangione’s. This spring, Chief Judge Robert Molloy, of the federal district court in the US Virgin Islands, took issue with a Justice Department request to pause a noncapital prosecution well on its way to trial—all because prosecutors wanted time to reassess the Biden administration’s decision, made in February of last year, to not pursue a death sentence.

Bondi’s reversal in the Virgin Islands case, a murder prosecution, prompted the judge to immediately appoint a defense attorney “learned in the law applicable to capital cases,” as the law requires. And then the judge sternly denied the government’s request to pause the case, strongly implying that he might strike the belated death notice altogether. (Mangione didn’t have his own capital counsel until February, when a judge appointed one such lawyer on the eve of Bondi’s new death penalty policy.)

On August 18, Molloy struck the notice, letting the case proceed as a noncapital case. In quick succession, another judge in the same district announced her own intent to strike two other death notices in cases where a noncapital trial was “fast-approaching,” according to The Virgin Islands Daily News.

These judges didn’t act in a vacuum. Molloy relied on the “persuasive” reasoning of two other federal judges, in Nevada and Maryland, who were among the first to block the Justice Department’s about-face from the Biden years. In May, with 12 days to go before a scheduled trial in Nevada, a federal judge excoriated Bondi’s Justice Department for filing a death notice in a case where the Garland Justice Department, some eight months earlier, had already declined to do so. In a lengthy order striking down the death notice, the judge explained that the government’s maneuver, characterized as “a wholesale reversal at the eleventh hour,” went against “the Court’s orders, its statutory obligations under the Federal Death Penalty Act, and Defendant’s rights to due process and a speedy trial.”