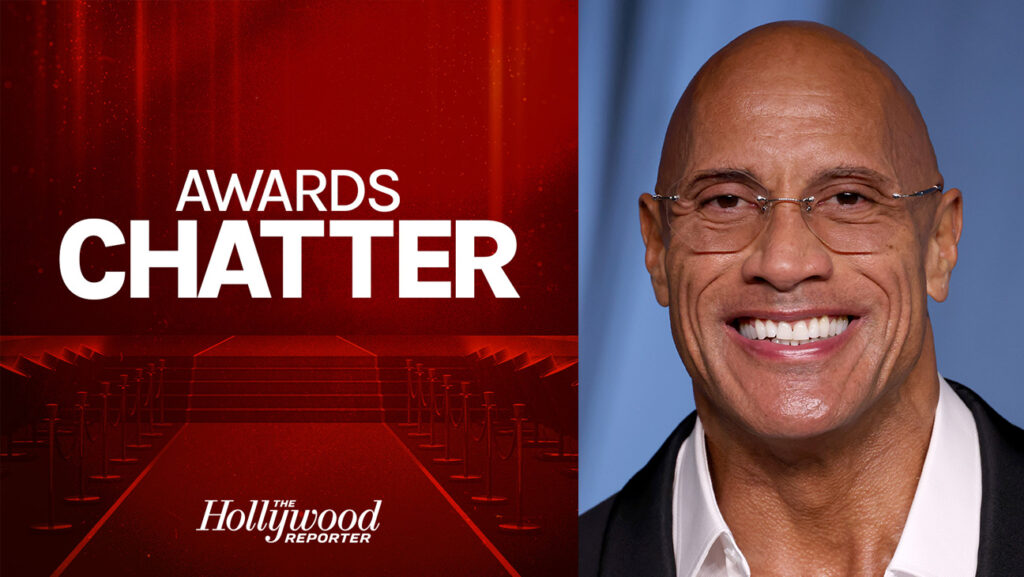

“I was ready to chase the challenge and not chase the box office,” the wrestler-turned-actor Dwayne Johnson said in reference to his latest film — Benny Safdie’s The Smashing Machine, an A24 production in which Johnson portrays Mark Kerr, an early MMA fighter whose life took a dark turn — during a recent recording of The Hollywood Reporter’s Awards Chatter podcast in front of 500 film students at Chapman University in Orange County.

From most people, such a statement would not seem particularly significant — but Johnson is not most people. He is the most bankable movie star of his generation.

The 53-year-old was identified by Forbes as the top-grossing actor in the world in 2013, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2024. He is the fifth-highest-grossing actor of all time — the 40 films in which he has starred, mostly action films and family comedies, have collectively taken in just under $14 billion worldwide, or an average of $349.7 million. And within the last year, he had two movies open at number one at the box office in the same calendar month — Moana 2 and Red One — something no other actor or actress had achieved in the last 27 years.

Consequently, there has long been an expectation that when Johnson stars in a film, it will be a blockbuster. But there also has long also been an expectation that when Johnson stars in a film, it will be entertaining but not particularly deep or challenging. The Smashing Machine defied both expectations.

The film, for which Johnson added 32 pounds of muscle, changed the walk he walks and talks, and displayed an emotional vulnerability that he had never previously shown on screen, has brought Johnson the best reviews of his career — the New York Times called his performance “the magnetic center of the film” — as well as best actor Oscar buzz. But it has also joined fellow awards hopefuls One Battle After Another and Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere in the category of commercial underperformers, having cost approximately $50 million but grossed just $20 million in its first month in theaters.

The question now is whether members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will penalize a challenging film for not doing the sort of business that a fluffier film might have, or reward Johnson for digging deeper than ever before. Regardless, Johnson’s own feelings about the film are crystal clear: “Smashing Machine completely changed my life in ways that I didn’t anticipate, because of what it represents. It represents, for me, listening to your gut, to your instinct, to that little voice. Sometimes in life, you think you’re capable of something, but you don’t quite know. And sometimes it takes people around you to go, ‘Come on, you could do this.’ Smashing Machine also represents a turning point in my career that I’ve wanted for a long time: for the first time in my career — 20 plus years since The Scorpion King came out — I made a film to challenge myself and to really rip myself open and to go elsewhere and disappear and transform. And not one time did I think about box office.”

He continued, “Even though we didn’t do well [at the box office], or as well as we wanted to, it was okay because it just represented the thing I did for me. Maybe it was because I was an only child, but all the stuff that I had experienced as a kid and as a teenager — eviction, my mom tried to take her life two months after we got evicted and I pulled her out of the middle of the highway, a whole bunch of stuff happened — I had rejected exploring any of that on film. For years I would do these other films that were big and fun, Jumanji and Moana, with a happy ending, and I love that still. But what this represented was, ‘Oh wait, I can do the thing I love, which is to tell stories, but I could also take all this stuff and have a place to put it.’”

In response to questions from yours truly and from students — you can read a transcript, lightly edited for clarity and brevity, below — Johnson spoke about his entire life and career, as well as assorted topics like how he knew and tweeted about Osama bin Laden’s death before it was even announced by President Barack Obama; what he was thinking in the famous photo of the Oscars audience reacting to the La La Land/Moonlight screwup; and how he feels about the prospect of one day hosting the Oscars — or perhaps co-hosting, with pals and repeat collaborators Kevin Hart and/or Emily Blunt.

Perhaps most poignantly, he talked about how his time in the ring helped to prepare him for acting: “That taught me that idea of always taking care of the audience, doing your best to send them home happy, and believing in what the performance is. My ring was my stage and the character was who I thought was interesting and intriguing.” He added, “I never was interested in being the biggest guy or the loudest guy or the craziest guy or the guy that did all these crazy moves off the top rope, because that just wasn’t me. But I thought, ‘Maybe I could be the most entertaining.’”

* * *

I’d like to go back to the very beginning and ask you to share where you were born and raised, and what your folks did for a living.

Well, I was born in San Francisco, California, about 1,000 years ago. And for those of you who may not know, my dad was a professional wrestler. Today, wrestling is global and it’s publicly traded. Back when my dad wrestled, it was hard; if you think about Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler from Darren Aronofsky, it was that kind of life. And my mom was the daughter of my grandfather, who was also a pro wrestler. That’s how my parents met. They were in San Francisco when my dad was tag-teaming with my grandfather, and my grandfather said to my dad, “Hey, don’t worry about going to a motel tonight. Why don’t you come stay at our place?” And he said, “Okay, sure,” and he met my mom. And then couple of months later — nine, to be exact — I was born. My dad’s Black, my mom’s Samoan, and here I am.

You began getting up early to go to the gym with your dad at the age of five. At 11, you first met the person who co-founded what was then the World Wrestling Federation, or WWF, and later became WWE, Vince McMahon. But you weren’t really thinking of pursuing a career in wrestling until after a few things happened in your mid-teens, right?

In the world of pro wrestling at that time, there were many different promotions and organizations across the country. People would wrestle in a local territory — say, for example, Texas — for maybe a year, year-and-a-half, and then their run would be done and they’d go on to the next territory. I lived in 13 different states, mainly throughout the South, a little bit up in the Pacific Northwest, a lot in Hawaii, and then in New Zealand. I was all over the place. When we were in Hawaii — my second time in Hawaii — and I turned 15, unfortunately we came home to an eviction notice. We lived in a small efficiency, and there was a notice on the door that said, “You have five days to get all your stuff out. If not, you’re going to be removed by the police.” We were forced to leave the island because we had no place to live. I went to Nashville, Tennessee, of all places, where I was supposed to meet my dad. It didn’t work out for us in Nashville, so we went to, of all places, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Really quick story, because I think it’s important. You know how we have these moments in life that are defining for us and change our life? I had been getting in trouble a lot in Hawaii — I was getting arrested a lot, I was doing a lot of things that I shouldn’t have been doing and I had a hard time staying on the right track — and I was still getting in trouble when I landed at Freedom High School in Bethlehem. First of all, the kids thought I was like an undercover cop because I was 15 and I looked like I was 47 — I had a mustache, I was like 6’4″, 220. Within two weeks, I was suspended for fighting. When I got back to school, I had to go to the bathroom, but I didn’t want to go to the boy’s bathroom because it was just nasty, so I went to the teachers’ bathroom. Then a teacher comes in and he goes, “Hey, you got to get out of here.” I was washing my hands, and I went, “I will when I’m done” — I was like being a real punk — and then he goes, excuse my language, “You got to get the fuck out of here right now!” And he like hit the wall, he was so angry. I took my time, I dried my hands, I brushed by him and gave him a little, like, shoulder brush.

I had also just been arrested for theft. My mom had to come to the police station. We were fresh in Bethlehem, and now this was our reputation. And I remember thinking that night, “Wow, I’ve embarrassed my mom,” which is the last thing I wanted to do. I had a complicated relationship with my dad, but I really embarrassed my mom and I felt so bad. And then I really embarrassed myself with this teacher. And I thought, “God, this is not me.” So then the next day, I went to school and I found the teacher and I went to his class. He just happened to be the teacher who taught all the bad kids. So I came to his class and he’s looking at me and he goes, “Yeah?” And I said, “Hey, I just want to apologize to you for how I acted.” And I went to shake his hand, and he looked at my hand, and he looked at me, and he finally shook it. He said, “Thank you.” And then I go to pull my hand away, and he holds onto my hand, and I’m like, “Oh man, this is not good. He’s going to hit me or something.” And he goes, “Hey, I want you to come play football for me.”

This is Jody Cwik?

Jody Cwik, yeah, thank you for doing your research. This guy saw a little bit of potential in me, I think, once I apologized, and then he really just changed my life, because he set me on a path. He’s passed away since, but thank you, Jody, for changing my life.

You ended up with a scholarship to play football at the University of Miami, and were an All-American defensive tackle there, part of a team that won the national championship in 1991. But just when things seemed to be going well, you got seriously injured — your shoulder and back — and there went the hope of doing this professionally. There was a brief period after when you played in Canada, but that didn’t work out. You were cut from the practice squad, you didn’t have a car and you didn’t even have enough money to get home. It’s 1995. You’re 23. Can you take it from there?

I didn’t have shit, by the way, yes. I had worked so hard since I was 15 and Jody Cwik said, “Hey, I want you to come play football for me, I think you have some potential.” My goal was to play in the NFL. I thought that was going to be my ticket out. I thought I was going to be able to buy my parents their first house. We had never lived in a house; I was a trailer park kid. And then when it didn’t happen, I went and played in the Canadian Football League for about a half a season. I got cut from there, and then you realize, “Oh, it’s over. The dream is over. It is completely over. Now, what do you do?” I had graduated from Miami and I had a degree, but I didn’t know what to do. That was my second bout of depression, actually, when I got cut from the CFL and I had to move back in with my parents. I hated it, because all my friends had been drafted in the NFL, and they were making money and I wasn’t. Then I got a call from the CFL coach who had cut me and he said, “Hey, I’ve got some really good news. I want to bring you back next year.” My dad is sitting right there, and I’m on the phone, and he hears me talking, and I’m like, “Thank you, Coach, I really appreciate it. But, you know, I think I’m going to close this chapter in my life. Thank you.” I could just feel my dad looking. I hung up and my dad said, “Who was that?” And I said, “That was the coach” — his name was Wally Buono. And he goes, “What’d he want?” I said, “Well, he wanted to offer me a tryout for next season.” And he goes, “Great.” And I went, “Well, I’m not going to take it.” And he was like, “What do you mean you’re not going to take it? This is your opportunity.” And I said, “I think I’m going to close that chapter of my life.” And he goes, “Well, what are you going to do? ” And I said, “I think I want to try my hand in the business.” And he goes, “What business?” I said, “Professional wrestling.” And he was so pissed, and we got into a huge fight that night—

He was pissed because that was “his” business or because he didn’t want you to make the mistakes that he had made?

I think it was both, I really do. I had a complicated relationship with my dad and I think it was, “Hey, this is my business, not yours.” But I also feel like it was, “Hey, look around — I’ve been in this business for 30 years and I’m living in this little apartment paying 500 bucks a month in Tampa, Florida. I don’t want this for you, I want something more for you.”

Johnson (94) during a 1994 University of Miami football game in 1994.

So you started wrestling in 1996 and got a taste of what you were describing earlier — that Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler sort of life. And while I know that competing at that level was not what you had dreamed of doing, I do wonder if some of the showmanship that later defined you when you made the big time as a wrestler, and then when you became an actor, traces back to that period?

No doubt. Before I got to the WWE as The Rock, I had to cut my teeth and make my bones in a smaller wrestling organization down in Tennessee. I wrestled every night in flea markets and state fairs and car dealerships — wherever you could put up a ring — and the amount of money per match that I was guaranteed was 40 bucks. I was wrestling maybe five, six times a week. You’re making no money, you’re starving, but you love what you do. I loved playing football, but with football I played with Ray Lewis and Warren Sapp, incredible players, and I thought, “I’m good, that’s great.” But when I started wrestling and performing in front of people, I was like, “Oh, this is what I love.” Even though I was performing for maybe 50 people in a barn sometimes, I still loved it. And, yeah, that taught me that idea of always taking care of the audience, doing your best to send them home happy, and believing in what the performance is. My ring was my stage and the character was who I thought was interesting and intriguing.

At that time, your character was “Flex Kavana,” right?

Flex Kavana. Don’t judge me, I know.

Who would then become, once you got to the WWE, Rocky Maivia, a tribute to your dad and grandfather, right? Those are their names.

That’s right.

I don’t think it’s nice when people say professional wrestling is “fake,” because although there’s an acting element and a setup element, it’s still very real in a lot of ways. But you are assigned a kind of persona, right? I’d like to ask you to talk about the persona that you were given out of the gate and the turning point that arrived at WrestleMania 13 in Chicago in 1997.

When I was sent down to Memphis to learn, I met with Vince McMahon and he goes, “You’re not ready for the WWE. You have to go learn how to work, how to wrestle and the nuances of the business.” Nuance and pro wrestling, those two words or phrases don’t always go together, but there is nuance to it if you’re open to it, and you can learn. It’s same thing with art and film and performance. So when he called me up to the WWE, he said, “What are your goals?” I said, “Well, my goal is to have a great career, but it’s important to me to carve my own path. My grandfather was a wrestler, my dad was a wrestler, I love and respect what they’ve done, but maybe there’s a way that I can do it on my own and not rely on that.” And he goes, “Yep, absolutely. It’s great idea. So you’re going to take the first name of your dad and the last name of your grandfather.” And I went, “Oh, I don’t know about that.” But he was the boss, so I took it. And what happened in the WWE? I made my debut, and you talk about sink or swim, my very first match ever in the WWE was in Madison Square Garden on a pay per view called Survivor Series. And I remember Vince said, “Hey, you’re going to sink or swim tonight.” And I said, “Great. I can’t wait.” I said, “What’s the finish of the match?” And he said, “Well, you’re going to win everything.” I went, “I’m sorry, what?” He’s like, “I’m throwing you into the fire. You’re going to win everything. I think you have a little bit of potential, but we’re going to see.” And I was like, “Fuck.” I’m so nervous at that point. And then I go out and I have the match. And it was a really great match. I’m always careful not to say “I beat this guy” or “I beat that guy” because, really, they allowed me to win, so I’m grateful for that. Those guys were really great that night. And eventually I became the youngest Intercontinental champion in the WWE. But then this interesting thing happened, and I think it can apply to everyone in the room here as you all are on your artistic endeavors down the road. Vince had said to me, “Hey, when you go out and you wrestle in these matches, I want you to smile.” And I went, “Okay. Why?” He goes, “Because I want to make sure that everybody knows how grateful you are. So when you hear your music, go out and you smile. After the matches, when you’re walking back, I want you to smile.” And I went, “Okay. Got it. Even if I get beat?” And he was like, “Yeah. Even if you get beat.” And I went, “Okay.” It didn’t feel right, but he was the boss, and I didn’t know what I didn’t know. But this interesting thing happened where audiences in every arena across the country started to feel like, “Oh, this guy? You’re full of shit. You’re smiling even though you just got your ass kicked? I thought you came from the Miami Hurricanes where you guys were balling down there. Who is this dude?” It just started to feel false, and you know what? It was. And eventually steam started to pick up where fans just rejected that. You mentioned WrestleMania 13. I love Chicago today—

But not then.

But then Chicago was known, in wrestling parlance, as a “heel” town, meaning, they love the bad guys. And I was not a bad guy at that time. I was this good guy who was not being real—

A “babyface.”

A “babyface,” that’s right. And Chicago said, “That shit ends tonight.” So that night in Chicago, there were 15 or 16 thousand people and they were all chanting, “Rocky sucks!” And when 15,000 chant that, it’s resounding. And that night, it changed my life and it changed the course of my career, because then Vince and all of the agents at that time in wrestling said, “Oh, we did something wrong.” I came to the back and he said, “Why don’t you go home? I’ll call you this week. We need to figure something out.” So he called and he goes, “Hey, we’re going to take the Intercontinental title off and make somebody else champion.” I wound up getting hurt that week, so I had to take off time anyway. But I realized in that moment that the most important thing, whether it’s in wrestling or what I do now or whatever you guys are going to do in the future, the most important thing — and it’s easier said than done, but it’s so true — is to be yourself and be authentic.

Johnson, early in his career, wrestling Hulk Hogan.

So even though I don’t think that you, as Dwayne Johnson, are a heel, that meant turning heel? That happened in August 1997. In 1998, you won the WWF Championship for the first time, and became “The People’s Champ” with “The People’s Elbow.” You ceased being Rocky and became The Rock, and began referring to yourself in the third person. And you became the king of insults, as well. Which insults would you put at the top of your list?

I would say—

And I could say, “It doesn’t matter!”

“It doesn’t matter!” It doesn’t matter is a good one. At that time in wrestling and the WWE — the “Attitude Era,” and not being a publicly traded company — everything just flew under the radar, and I realized at that time, “Oh shit, I can say anything.” I never was interested in being the biggest guy or the loudest guy or the craziest guy or the guy that did all these crazy moves off the top rope, because that just wasn’t me. But I thought, “Maybe I could be the most entertaining.” Like, “Oh, I love this song that just happened on the radio. Maybe I could sing that song but change the lyrics and talk shit to somebody, and bring out a guitar. Maybe that’s the way to go.” So I would do crazy stuff like that. Then I just started coming up with these insults — the kind of shit that I would love to say, or that other people would love to say, to their friends, their boss, their coworkers, things like that — “It doesn’t matter,” “a big tall glass of shut up juice,” or “take your idea, turn it sideways and stick it straight up your ass.”

“Jabroni.”

Jabroni.

“Smackdown.”

“Smackdown Hotel.” I started singing Elvis, but turned “Heartbreak Hotel” into “Smackdown Hotel.” I’d sing in front of the audience, just sing to the opponent. A lot of crazy things like that.

It clearly resonated with a lot of people and you became the fan favorite. And then came acting. I could be wrong, but I trace it back to March 2000 when, because you were so popular as a wrestler, you were invited to host Saturday Night Live. Not long after that, you started to appear in bit parts, and a sitcom, and things like that. But before we talk about your move into films, I wondered, was the idea of using your popularity in wrestling to get into acting — was this something strategic? Was it McMahon saying, “Hey, this would be great,” or was it you with some sort of a plan? Now moving from wrestling to acting is something that a lot of people have done, but back then it was not common or easy to do.

No, it wasn’t, Scott. It was actually harder back then because I think wrestling was looked at in a certain way; it wasn’t revered like, “Well, what a performance you put on at WrestleMania!” It was like, “Oh, that’s that wrestling thing.” And I got it. I understood. With Saturday Night Live, I got a call from Lorne Michaels, who said, “Hey, I’d love for you to host.” I was like, “I would love to host.” And I said, “I have one request that I would ask that you consider.” Because you’ve got to know your audience, and it’s Lorne Michaels, and you don’t want to go in and say, “Hey, here’s my demands!” I said, “I’d love for you to consider this.” He said, “What’s that?” I said, “I’d love to do no wrestling skits at all because I feel like that’s kind of low-hanging fruit. I want to do everything else but that.” And he goes, “Okay. What a great challenge.” So I did that. I hosted the show. The show went great. And then I remember at that time I was hoping to just do more — I wanted to expand this idea of what it was like to perform and to entertain. I thought, “Oh, I would love to act.” I had done a bit part in Star Trek and a few other things, and I loved it — it was so good — and I was just waiting for that opportunity. And then after Saturday Night Live, I got a call from a director, Stephen Sommers, who was, at that time, the director of one of the biggest franchises in the world, the Mummy franchise, starring Brendan Fraser. He goes, “Hey, I have this role for you. It’s called the Scorpion King. Can you come in and can we meet about it?” And I went, “We can.” We had a great meeting, and he and Universal offered me the part. Brendan Fraser, at that time, was one of the biggest stars in the world — he had this throwback look to him, and he was the man — and I remember thinking, “God, is he okay with this? Because this is his franchise.” And I remember pulling Stephen aside and I said, “Hey, is Brendan okay with this? Can I call him can?” He was like, “Not only is he okay with this, but he wants you to be in this.” It was so awesome, and I’ll never forget that. He could have, at that time, because he had the juice, gone, “I don’t know. Let’s get somebody else. I don’t know if I want The Rock in this, who’s never acted before other than what he’s done in the ring.” I’ll never forget that. And to this day, we’re great friends and I really appreciate him.

I’ll just note that in September, at the Toronto International Film Festival, you guys had your North American premiere of The Smashing Machine, but it was a very late screening, so there was a party beforehand, and I looked over and saw Brendan Fraser, who was in town for the world premiere of Rental Family, coming over to talk to you. It must have been a full-circle moment.

He came to this dinner party just to see me and say hello and give me a big hug and tell me couldn’t wait to see the movie. I won’t share what else he said, but it meant so much to me.

The Mummy Returns came out in 2001. You were in it for just seven minutes — it was basically a cameo — but from what I understand, your appearance was so well-received by test audiences that before the film was even released, the studio approached you about starring in your own spinoff, which is what became 2002’s The Scorpion King, and made you the highest-paid first-time lead of a movie ever. It all happened so fast. What do you remember most about that period?

It was crazy. I just wanted to grow. I remember being in wrestling and looking into the WWE locker room at that time and looking all these guys that I’d wrestled — from Stone Cold Steve Austin to Kurt Angle to Triple H to Brock Lesnar and all these guys — and thinking, “What’s next? What does this idea of ‘more’ mean?” And then I go shoot The Mummy Returns in Morocco, and we’re in the middle of the Sahara Desert, and again, I have this idea in my mind, “What’s next? I want more. I’m getting restless.” But I didn’t know the moves to make. At that time, I didn’t have an agent. I was flying by the seat of my pants.

You were just starting to work with acting coaches, right?

Starting to work with acting coaches — Larry Moss, Howard Fine, Aaron Speiser, love those guys. But I remember being in the middle of the Sahara Desert shooting. I was sick — I ate something bad over there, and I had a hundred-something fever, and it was 115 degrees in the Sahara Desert, and I had a blanket over me because I was freezing, and Stephen Sommers, before he yelled action, goes, “Hey, are you okay?” I’m like, “Yeah, I’m going to be fine.” When really I’m like, “Fuck, I’m going to die here. I think this is it. This is how I go out. All right. I got to make it good.” And then for my first action scene as the Scorpion King in Mummy Returns, he called “Action!” Stuntmen were flying everywhere. And he yells “Cut!” And I know it sounds weird to some, but not to you: that idea of getting “bit by an acting bug,” or a directing bug, a writing bug, whatever that is? I got bit by it. And I knew in that moment, “This is what I want to do. This is what I was born to do.”

The Scorpion King

Universal Pictures/Photofest

It wasn’t long after that that you phased out wrestling for a while and began acting a lot — 2003’s The Rundown, 2004’s Lawman and Walking Tall, 2005’s Get Shorty sequel Be Cool as a gay bodyguard. By the way, did Elmore Leonard say that he wrote that in the book version with you in mind, when you weren’t yet even an actor?

He did.

Then there was 2006’s Southland Tales and Gridiron Gang, which was, I believe, the first time you were credited in a movie as Dwayne Johnson as opposed to The Rock. But you’ve talked about how, somewhere between 2008 and 2010, you were getting a bit frustrated. The movies were doing very well commercially. Around that period, there’s a Disney movie, 2007’s The Game Plan, 2009’s Race to Witch Mountain, 2010’s The Toothy Fairy— [Students are applauding loudly for each title.] Now, these guys love those because they grew up on them.

Grew up on them. Yeah. That’s so cool.

But in that moment…

I had a different experience.

Race to Witch Mountain

Walt Disney Pictures/Photofest

Yeah. And I’ve heard that these frustrations were brewing for you and ultimately culminated in a big meeting with your agents at the time.

Thank you for the love, I really love that, and I get that with those three movies in particular, those family films — Game Plan, Race to Witch Mountain, Tooth Fairy even. But that was three in a row after starting out my career as an action star. Then I did a couple of years where it was just back to back to back. But the truth is — and I can look back on that time with real clarity these days — those days, things were a little cloudy. I loved making those movies. I also think I manifested those because I don’t think I was ready for anything other than easy, light, family films that made me feel good. At that time, I was also going through a separation and a divorce. When you guys get married, as a few of you may know, you sign up for the long haul, but then it doesn’t always work out like that, and then it rocks you like it rocked me. And we had a baby, and what kind of father was I going to be? Anyway, I feel like at that time, I was really going through it. That was another bout of depression. I was trying to figure my stuff out, and that was the only thing that I really wanted to do artistically; I didn’t want anything that was going to challenge me to rip my guts out, I wanted stuff that has a happy ending, and so that’s what that was. Not only did I want that, but also, the people [representatives] around me — I remember challenging them and saying, “Hey, I may be in this funk right now, and I’m going to work hard to work out of it, try my best. But also I need some guidance here.” I remember having a meeting with my agency at that time, and I said, “Hey, I know I’m in a different spot, but I’m looking at the biggest stars in the world — George Clooney, Will Smith, Johnny Depp at that time — and I want to have a career like that.” I was like, “All right. What do you guys think?” And it was like crickets in the room. And I was like, “Okay. Say no more.” And I remember thinking, “Well, maybe it’s time for a change.” I made a decision at that time that I was going to make a big change, and I just collapsed the infrastructure around me to build something new back up.

Which I guess you could say in a way, started with 2011’s Fast Five, 2013’s Fast & Furious 6, 2015’s Furious 7, 2017’s The Fate of the Furious and 2019’s Fast and Furious Presents Hobbs & Shaw. Just to give some context, Fast Five, the first one that you appeared in, made almost twice as much money as the prior installment, starting a new chapter beyond the family-friendly comedies and stuff.

Fast Five

Jaimie Trueblood/Universal Pictures/courtesy Everett Collection

There was also 2013’s G.I. Joe: Retaliation and Pain & Gain; 2014’s Hercules, with you stepping into the shoes of a guy who decades earlier had traveled a similar path to you, the bodybuilder-turned-actor Steve Reeves; 2015’s San Andreas and, starting that year, Ballers on HBO, which you produced and starred in. And then there were the comedies starring everybody’s favorite odd-couple, you and Kevin Hart, 2016’s Central Intelligence, 2017’s Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle and 2019’s Jumanji: The Next Level. [The students particularly applaud the Johnson/Hart collaborations.]

Thank you for all the Jumanji love. I’m happy to announce to you guys here at Chapman that in less than three weeks we’re starting Jumanji 3. It’s very cool. There will be no Kevin Hart — yeah, he’s just greedy, he wants too much money, but it’s okay. No, I’m only kidding! We can’t wait. It’s going to be awesome. And Jake Kasdan is back, he’s going to direct. Oh, and very cool is that for the first time in all our Jumanji installments, we’re bringing it back home: we’re shooting in LA.

Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle

Frank Masi/Sony Pictures Entertainment

Talking about bringing it back home, we cannot gloss over a thing that really connects you back to your culture and grandfather and singing, and that is Moana, the first installment of which came out in 2016 and the second in 2024, with a live-action version coming next year.

Playing Maui has been the gift of a lifetime. Growing up as a Samoan — half Samoan and half black — in Samoan culture, Polynesian culture? We’re proud people. Proud of our culture. And what Moana has represented is a really awesome global embrace of Polynesian culture, our values and our qualities and our pride and our mana. Today’s Tuesday. Just this past Friday, around 8:00 pm, we officially wrapped the live-action version of Moana, so we can’t wait. This upcoming summer, you guys will see live-action Moana, and it’s going to be pretty cool. I spent an entire week shooting “You’re Welcome,” and the singing and the choreography is crazy. [Students whoop with excitement, urging him to sing it.] No, no, no, you’re not ready for that. No, you’re not ready. [Johnson sings “You’re Welcome” and the students go wild.]

Moana

Disney

The hits keep coming: Rampage and Skyscraper in 2018; 2021’s Jungle Cruise, which marked the beginning of your collaboration and friendship with Emily Blunt, which connects to The Smashing Machine; and 2021’s Red Notice, which was the most watched film ever on Netflix until KPop Demon Hunters.

In our house, we’re big Kpop Demon Hunters fans!

2021 also marked the beginning of Young Rock, the NBC show looking at three periods of your youth. And then, in 2022, came something that I know you’d been thinking about for many years, which marked your first footsteps into the world of comic book adaptations, and that was Black Adam. Was your time in the ring as a heel of any value in playing Black Adam?

Oh, absolutely. I feel like not only my time as a heel in the ring in wrestling, but it was almost like the anti-hero that eventually the Rock became. I loved making Black Adam. We had a great time. Loved creating those characters and introducing other characters, as well, in that universe. Had a great time. Wish that universe well. And on to others.

Black Adam

Everett

All right, we now come to a major milestone in your career, and that is The Smashing Machine, which the audience here has just seen. You’ve said that a few years ago you essentially began asking yourself, “Am I actually doing what I want or am I doing what the people around me want?” Emily Blunt, who, again, has known you since at least Jungle Cruise about five years ago, has said of you, “I think he’d been feeling a fatigue at being the person that everyone expects him to be.” Just a little bit of context, perhaps, for your decision to pursue a film about someone who had actually been on your radar for a very long time.

You know how you hear that voice sometimes, the voice behind your rib cage? Sometimes it speaks softly to us and knocks like, “Hey, listen to me.” Sometimes it’s quiet, sometimes it’s soft, sometimes it’s resounding, and sometimes it’s loud and beating you like, “Hey, come on!” I had that voice for some time. By 2018, 2019, I just felt like, to be honest with you, I was tired of being comfortable. There’s something intriguing to me about being uncomfortable and not knowing all the answers. The big movies are fun and they make a lot of people happy, including myself and my family and a lot of families around the world. But I also felt like there was just more, and I felt like I should challenge myself, and I was ready to chase the challenge and not chase the box office. I didn’t quite know what the move was, because there was no blueprint like that for me. I was like, “Man, how do I do this?” But in 2019, I got a hold of this documentary that I watched, [2002’s] The Smashing Machine, and I really loved it. It was a compelling story and I felt like, “Hey, I know this guy.” And I did know Mark. I met him in the late ’90s when he was ascending. Then I saw the documentary. And I had just watched Uncut Gems. I happened to connect with Benny on this, and he really connected with the material. I got to know Benny very well, and we decided that we were going to make The Smashing Machine — and then COVID hit and shut everything down. It went away. Benny went away. I went away. He had commitments. I had commitments. Emily became one of my best friends. We worked together on Jungle Cruise. And then she called me one night when she was shooting Oppenheimer and she said, “Hey, I was just with Benny Safdie this afternoon and he was asking me about you. Did you guys have something together?” I said, “We did. We had something called The Smashing Machine.” And she goes, “Did you ever get the sweater?” I went, “What sweater?” In the movie, Mark Kerr is wearing a yellow Nautica sweater towards the end when he’s in Japan. Benny, unbeknownst to me, had found the sweater online, sent it to me with a handwritten letter in the beginning of 2020, and said, “I don’t know if I’m going to ever be a part of this, but I believe in it so much and I believe in you so much, and I want you to have this sweater because I believe it will help you become Mark Kerr.”

Wow!

Wow — but I never got it! I never got the sweater. I never got the letter. He thought I ghosted him. And I thought he ghosted me. Emily goes, “Did you ever get it?” I said, “No, I never got it.” So she connected us via text. Emily also said, “Hey, can I see this documentary?” I said, “Yeah.” So I sent her the documentary that night. She watched it that night. And at 2:00 in the morning, she gave me a call — now mind you, she had to get up at 5:00 to do Oppenheimer — and she said, “I just watched this documentary. You have to make this movie. You have to make it with Benny Safdie. You were born to play this role.”

Johnson and Emily Blunt in The Smashing Machine

A24

Not everyone knows that there are major differences between MMA and WWE and UFC. Just because you’re a tough guy who fights in one way doesn’t mean you can easily transition to fighting in another. Talk about what you did to transform into Mark, even before you wound up in the makeup chair of perhaps the world’s greatest living movie makeup artist, Kazu Hiro, who won Oscars for turning Gary Oldman into Winston Churchill for Darkest Hour and Charlize Theron into Megyn Kelly for Bombshell. Mark walks differently than you, talks different than you, fights differently than you.

Sure, I’m happy to, because it was an honor to transform into Mark Kerr. I had to gain just over 30 pounds — 32 pounds — but Mark Kerr had a different quality of muscle because he was a wrestler, and when you’re a wrestler you have a non-stop motor, your cardio is through the roof, and there’s a lot of fast-twitch muscle fiber that you have to put on over the course of six months. Benny said something funny to me — he goes, “I don’t know if anyone’s ever told you this, but you’re going to have to get bigger.” I went, “Okay. In what way?” He goes, “I think puffier, maybe?” I said, “Let me think about it and I’ll get back to you.” But I realized that Mark Kerr had a different quality of muscle. So I had to put on 32 pounds of muscle, and I also still had to move because I had to be an MMA fighter. So I had a twelve-week training camp—

Forgive me for interrupting, but people should know, Benny also told you that he was not going to cut away from you fighting, so faking it was not an option.

Thank you for bringing this up, because I love this part — I love talking about Benny and his process and his signature style. He said, “Hey, I’d love to not cut away from you in these fight scenes.” And I knew what that means. That means I’m going to get my ass kicked and get my ass just rocked. And I said, “I would love that too.” He said, “Are you committed?” I said, “I am committed.” And that’s what we did. When you see the film, there are no cutaways. I felt like it was my accountability and my duty not only as an actor, but also as someone who’s embodying a real person who lived, who’s still alive, who paid the price and fought his demons and continues to fight his demons today. There was a voice transformation, as well. Mark speaks very softly and he’s very tender. He has this childlike curiosity about him all the time. But the thing that I didn’t anticipate until I was in the moment was the emotional transformation. I considered a career in MMA very early in my wrestling career — in the ’90s when they were chanting “Rocky sucks” — and I was like, “This is not the right career path for me.” Thank God I didn’t do that because I don’t like being punched in the face — that really hurts. If I had done that, it would’ve been to chase the dollar, because I just wanted to make money, I didn’t want to be broke. But what I realized over time — the most eye-opening thing — was that when these men and women, especially back then where there were no holds barred and no rules and no financial planning, when they lost they just had themselves, and they struggled. A lot of those guys struggled back then. Mark struggled back then. So the emotional transformation was something that I didn’t anticipate, that rocked me from day one when I got on set and became Mark, because you realize that it’s not the wins and the losses with these guys, it’s the pressure — the pressure to perform, the pressure to win, the pressure to provide for your family, the pressure to go to class, the pressure to be a good son or a good daughter, whatever. Some people do good with pressure and some people struggle. Mark struggled.

The Smashing Machine

A24

The Smashing Machine is different thing than anything you’d done before — and you got a 15-minute standing ovation at the Venice Film Festival, which clearly moved you. I know you’re still in it, as far as promoting the film, but can you step back for just a second and contextualize what it means to you to have pursued and achieved what you did with this movie? Was it fulfilling enough for you to want to do more of this moving forward?

Smashing Machine completely changed my life in ways that I didn’t anticipate, because of what it represents. It represents, for me, listening to your gut, to your instinct, to that little voice. Sometimes in life, you think you’re capable of something, but you don’t quite know. And sometimes it takes people around you to go, “Come on, you could do this.” Smashing Machine also represents a turning point in my career that I’ve wanted for a long time: for the first time in my career — 20 plus years since The Scorpion King came out — I made a film to challenge myself and to really rip myself open and to go elsewhere and disappear and transform, and not one time did I think about box office. In our world you’re like, “Shit, how are we going to look?” And then Friday night comes and you’re like, “Oh man.” You wake up Saturday, and sometimes you wake up feeling good, and sometimes you’re like, “Oh my God, didn’t do well.” I had not thought about that at all. And even that Friday night when we opened, I went to sleep peacefully and woke up peacefully because it represented this thing. And even though we didn’t do well [at the box office], or as well as we wanted to, it was okay because it just represented the thing I did for me. Maybe it was because I was an only child, but all the stuff that I had experienced as a kid and as a teenager — eviction, my mom tried to take her life two months after we got evicted, I pulled her out of the middle of the highway, a whole bunch of stuff happened — I had rejected exploring any of that on film. For years I would do these other films that were big and fun, Jumanji and Moana, with a happy ending, and I love that still. But what this represented was, “Oh wait, I can do the thing I love, which is to tell stories, but I could also take all this stuff and have a place to put it.” So you ask if I’m going to run towards this? We have a project with Scorsese, a project with Aronofsky. Yes, I’m going to run, put all my shit in that, and continue to challenge myself. Anyway, Smashing Machine, as you see, was an opportunity of a lifetime that did change my life.

We’ll close with some rapid-fire questions from me — seeking just the first thought that comes to your mind about a variety of things — and then some student questions. What’s the acting role that got away?

Well, it’s one that I love that didn’t happen only because it was never offered to me and it was well before my time: It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s one of Benny’s favorite movies, and it’s my favorite movie. And the connection to Smashing Machine is that from the beginning of that film to the end of that film, nothing changes except his perspective on life.

As a wrestler, what was your best moment in the ring?

I had a match in Hawaii. Hawaii always meant a struggle for us because we were evicted. So the idea that I was able to go back and wrestle as the Rock, that was really cool and very special to me.

What’s your training schedule?

I like to wake up before my babies get up. I’ll do a little bit of cardio, and then I’ll go work out a little bit later.

What’s your favorite and least favorite thing to do in the gym?

My favorite thing to do in the gym is legs. And my least favorite thing is legs because that shit hurts.

What’s your favorite cheat food?

Well, one is tequila. The other is French toast. I’m also one of those weird guys who put peanut butter on a lot of things.

I want to show you a photograph and ask what was going on in your mind. This is the moment after the wrong best picture winner was announced at the Oscars in 2017.

Al Seib/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

I’m thinking, “There’s some shit going down and I may need to stand up any second. I need to protect Meryl Streep because she’s right there. Ben Affleck is looking over there to the right, he’s looking at Matt Damon. And there’s Sting in the background.” It was a wild moment.

Would you ever host — or perhaps with Kevin Hart or Emily Blunt or someone else, co-host — the Oscars?

Oh, that would be fun. Yeah, that would be cool.

I want to show you a screen grab of a tweet that you posted on May 2, 2011—

Oh my God, this is not good.

Before anyone else in the world had reported the news that Osama bin Laden had been killed, how did you know that had happened?

I’ve got a friend of a friend who gave me a call. The call was like, “Hey, this thing happened.” And I said, “Okay, wonderful news.” I was told on the call that the president at that time [Barack Obama] was going to make his speech in 20 minutes or whatever. I said, “Okay, great.” So 20 minutes go by, and at about the 25th minute, I tweet this. Then I get a second call, and the call is, “Yeah, the president didn’t go on yet.” And I went, “Oh shit.”

In 2022, both major political parties apparently reached out to gauge your interest in running for president. You obviously did not choose to get involved for 2024. On Young Rock, you run in 2032. Is there any chance that, in real life, you might entertain the possibility of running for president in the future?

Brother, you’ve asked a lot of great questions. Let’s ask another one.

Haha. Okay, let’s go to some student questions…

Student: Your screen persona, for so many years, has been one of strength and control, but Mark Kerr dealt with a lot of pain and uncertainty. Was it uncomfortable or freeing to be able to show vulnerability on screen?

It was really freeing for me, to be honest with you. For a long time, there was an image that you had to live up to. I’m not complaining, but it’s not always the easiest thing. And it was really freeing collapsing the expectation of being somebody capable and knowing all the answers who can get the job done and galvanize people and things like that. What I loved about becoming Mark Kerr was that it’s just real. That’s real life and it’s who we all are at the end of the day — we’re all human beings and we all have our problems and our demons and our insecurities and the shit that we’ve got to deal with all the time.

Student: We recently read reports about the first AI “actress,” which sparked a lot of angst and discussion amongst real actors. What is your opinion about the situation and how AI is affecting Hollywood overall?

It’s happening so fast that it’s hard to keep up and it’s hard to contain. One of the anchoring things that’s important is making sure that we take care of our own and making sure that we hold on to our jobs. I feel deep in my bones that there’s no substitute for human creativity and human interaction and human emotions, so I think that’s the thing we have to protect and hold onto. And I also feel like it’s something to investigate and explore and try to understand what’s happening and how we could potentially utilize it to our benefit and not be fearful of it, because I don’t like to be fearful of things.

Student: I’m also from Hawaii. What responsibilities do you feel come with being one of the most visible Samoan figures in entertainment? And how do you bring practices of “fa’aaloalo” to Hollywood?

I feel like probably the responsibility that I have, like we all have, is to live with fa’a Samoa, live with aloha, and live with that spirit. I’m lucky and blessed to be in a position where I have a little bit of influence, and so I try to make the right decisions and act in a way that would make our family and our culture proud. For me, one of the most important things was always to let culture be the guide. And when you let your culture — whether Samoa, Hawaii, Tonga Fiji, New Zealand, Māori — be your guide, then you can never go wrong.

Dwayne Johnson at the world premiere of Moana 2 in Hawaii

Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for Disney

Student: In entertainment and in business, what are the most important qualities that you look for in potential collaborators?

I think the willingness to work hard. That seems simplistic, but there’s work hard and then there’s grit, and I think the willingness to go to that grit place. I always feel like if there’s a voice telling you, “Hey, you can do more,” then you’re right. If there’s a voice that’s telling you “I belong in that room,” then you’re right. If there’s a voice that’s telling you “I belong at that table,” then you’re right. I also feel like one of the most important things that I’ve learned over time is, no one’s going to give you anything. You’ve got to go after it.

Student: I wanted to ask how your process of preparing for a voice acting role, like the one that you’ve played in the Moana films, differs from preparing for a live action acting role?

I learned very quickly on Moana that life has to come through the voice and the voice has to have life. When you’re acting in live action, there’s a lot happening — your facial expressions, your body, your energy — but when it comes to voice acting, it’s just you in the studio. It’s a hell of a challenge. But there’s also a great benefit: you can have multiple takes, so there’s a freedom there too.

Student: What, these days, inspires you to hit the gym or work hard or pursue success in other ways?

The thing that inspires me these days is my babies and my family. What I realized over the past couple of years is that “success” is just being at peace with my decisions and with who I am. That takes time, by the way. That doesn’t happen overnight. So I wish that for you. I wish that for everybody. It goes back to the thing that we talked about earlier, which is easier said than done, but the most powerful thing we can be is ourselves. You know how we hear a lot about “No fucks given”? It’s kind of true. When you can be yourself, that’s a powerful place.