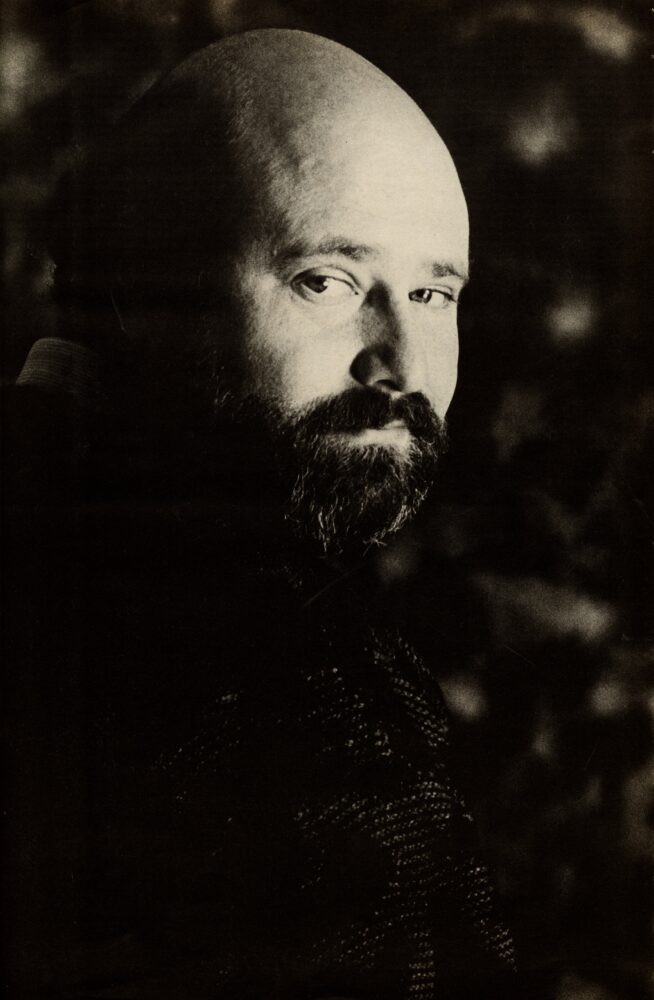

For the October 1986 issue of Interview, just two years after releasing This is Spinal Tap, the late Rob Reiner sat down with writer and producer Betsy Borns to promote Stand By Me, an adaptation of a short, coming-of-age story by Stephen King. The film felt somewhat autobiographical for the 39-year-old director, who as the son of Carl Reiner, the creator of The Dick Van Dyke Show, often felt isolated from his father. But unlike Gordie, the young protagonist in the film, Reiner had already begun making amends with his once-distant dad. As he told Borns at the time, “I’m just now coming to grips with being my own person. I’m a late bloomer, no question about it.”

———

BETSY BORNS: Stand By Me was an autobiographical story for Stephen King, but you’ve said that it was for you as well. It takes place in 1960, and the boys are twelve years old. Was that how old you were at that time?

ROB REINER: Actually, the book is set in 1960, but I set the film in 1959, because that’s when I was twelve. So yes, it’s autobiographical in that sense.

BORNS: I’ve read that you felt isolated as a child, like Gordie, the young boy in the film. Gordie is also alienated from his father. Was that the case with you?

REINER: Well, one strong element of the story was the notion of safety and understanding among friends, which I felt connected to right away. Once I had agreed to do the film, I was in a state of anxiety for a while because I didn’t know exactly what I was going to do with the story. Then I thought. Everyone associates Stephen King with horror and the supernatural. What made him write a literate, sensitive story like this?” I started piecing together little hints in the story, like how the boy feels he is unseen by his father.

BORNS: Did you feel that as a child?

REINER: Well, that part of the story hooked into me; that’s what I could relate to. My father loves me, of course, and now that I’m grown up and I’ve established myself, we have a very good relationship—there’s a lot of respect and he’s very proud of me— but as a kid growing up, I felt very isolated and misunderstood. I wanted this to be a story of how Gordie begins to accept and like himself, through the help of his best friend who’s able to see him a little more clearly than his father. He thinks his father hates him, doesn’t care about him, and these things have all been locked inside—until his older brother, whom his father loved, died. He’s left naked with all these feelings he’s never faced in his whole life. Very often tragedy will do that—because you face things you’ve pushed aside and haven’t dealt with for a long time.

BORNS: Is the body they’re looking for really the boy finding himself? And did you see it, on some level, as yourself?

REINER: Well, it starts out as a lark, but Gordie realizes there’s more to it; at one point he says, “You know, maybe going to see a dead kid shouldn’t be a party.” His friend Chris helps him discover himself, his sense of worth—that he has a gift for telling stories and he’ll be a great writer some day. And that’s happened to me now; that’s what I can relate to. Even though I’m 39 now, for the first time I am coming into my own a little bit. I’m establishing myself the way I would like to establish myself.

BORNS: Did you have a close friend like Chris as a boy?

REINER: I’ve always had close friends, even though I was never in one place long enough to have the same group. I always found much more comfort among my friends than I did with my mother and father.

BORNS: You came of age in the ’60s, which was the time of the “Generation Gap” —the time of turning to friends for solace and companionship instead of to parents.

REINER: I assume there are people who have great relationships with their parents when they’re growing up, but I think most people find validation and a lot of comfort and strength among friends. I think ultimately your parents probably care more about you than any friend could, but the fact is, you can have friends who really do care a lot.

BORNS: It’s interesting how your father is always talked about with his group of comic genius friends—Sid Caesar, Neil Simon, Mel Brooks—but you’ve also surrounded yourself with some of the most talented comic minds of your day—-Albert Brooks, Billy Crystal, Christopher Guest, Harry Shearer

REINER: When I was in my twenties and early thirties, those were the types of people who were familiar to me. The tone and noise that comedic people emit—it’s very soothing to me ultimately, because it’s what I grew up with. Comedians are the brightest people in the world. They observe life in a way nobody else does. I don’t know a co-median who hasn’t experienced a tremendous amount of pain, and they are, to me, the most insightful people there are. I don’t think I could ever be close friends with anyone who didn’t have a good sense of humor, but as I get older I find that’s not the primary thing I look for in a person. My best friends, Chris Guest, Billy Crystal, and Andy Scheinman [one of the film’s coproducers], all have a terrific sense of humor, but they also have a tremendous capacity to talk honestly about things. None of them feels compelled to perform and be funny. That’s very important for me. I find it incredibly draining to be around somebody who’s constantly on. I grew up with that. I can’t speak for my father; I don’t know how deep his relationships with his friends have gone, how intimate their conversations were, but I’ll bet they’re not as deep or intimate as the ones I’ve had with my friends. I think his connections with his friends were probably on a more superficial level. Although Mel Brooks is his best friend and they do see quite a bit of each other, and I’m sure they’ve had some meaningful talks over the years, I’d bet they haven’t had too many of them.

BORNS: Most comics say that to some degree comedy is a rebellion, a reaction against their parents in some way, like, “Oh, so you want me to be a doctor? Too bad, I’ll be a comedian instead!” For you, it must have been a difficult situation. You’re funny, but you couldn’t use that as a reaction against your father—it was like going into the family business.

REINER: In a way, Stand By Me is that reaction. I don’t think I’ll ever do anything that’s devoid of humor—I do have a sense of humor and I was raised around it-but this movie is certainly very far removed from anything my father has ever done or would even think about doing. Again, I’m 39, and I’m just now coming to grips with being my own person. I’m a late bloomer, no question about it—really a late bloomer.

BORNS: I’ve read that your father said you wanted to be him when you were young. Is that true?

REINER: He tells a story about how I came to him when I was a kid and said, “Dad, I want to change my name.” He figured, “Oh… he can’t deal with the pressure of the Reiner name.” He asked me what I wanted to change it to, and I said, “Carl.” Instead of being Rob Reiner, I wanted to be Carl Reiner.

BORNS: You said that you never lived by yourself until 1979?

REINER: Right. When I went through my divorce and left Penny [Marshall], it was the first time I’d ever spent one day living in a house by myself. These last six or seven years have been my growing-up period—I’ve gone through adolescence and everything else in the last few years.

BORNS: You were in analysis from the ages of 18 to 22. Was that helpful?

REINER: I don’t know that I really got much out of that… If anything it just opened the door a little bit, but I don’t think I made too many strides during that period, it’s only been recently.

BORNS: What happened?

REINER: Going through the divorce with Penny, leaving All in the Family—I pretty much said, for the first time, “I’m striking out on my own here.” I never felt, during any of that time, that I was living my own life. I thought I was an extension of my father’s life, and it was then that I said, “I don’t know what my life is, but whatever it is I’m going to try to figure it out and live it.” Slowly the pieces started falling into place, but it’s very scary at first to be in unfamiliar territory.

BORNS: And you’re not anonymous.

REINER: That was the toughest part. Here I was, completely established, a famous person, somebody whom everyone recognized on the street, and what I was looking for was acceptance as “me.” The public had already accepted me, but it was as a fake Rob and it didn’t fit— it was like a bad suit, and I had to get it altered. Meanwhile, when you take it off to get altered, you’re naked and everyone recognizes you. It was very odd and I had to be tucked away for a while.

BORNS: Didn’t you also have the problem of being typecast? You were “the Meathead” in everyone’s eyes— in addition to having a famous father and wife—so your whole character and life were pretty much mapped out for you. Did you turn away from acting to escape that?

REINER: Partly, yes. I like acting, but I certainly didn’t want to keep doing what I was doing. You get typed, though, and no one wants to see you do anything else, so I wound up not taking jobs. I would love to act in a movie with a good director and a good part, but I also understand, being a director, why a director wouldn’t hire me. You know the story….I went to see the movie Cleopatra after All in the Family had become very famous, and in it, Carroll O’Connor plays Casca. In the scene where they’re going to kill Caesar, someone in the audience yelled out, “Go get ’em, Archie!” It just destroys the reality… I still get “Hey, Meathead!”—not as much now, obviously, but it still feels odd. It’s so far removed from what I am and what I’ve been doing, but it happens. It’s funny because people who don’t know what I’ve been doing for the last four or five years say, “Hey, when are you gonna work again, Meathead?” I’ve been working harder in the last four years than I’ve ever worked in my life, but who the hell sees the director?

BORNS: You were on camera in Spinal Tap.

REINER: Yeah, but that’s a relatively small hard-core audience; All in the Family, in one night, was seen by 40 to 50 million people.

BORNS: How was The Sure Thing different from most teenage movies?

REINER: Most of them are about the first sexual experience—getting laid for the first time, guys looking through peepholes…. Ridiculous. This was about a boy who discovers that you can have a sexual experience that is connected with feelings of love.

BORNS: You have a very un-macho attitude about your directing—you even admit to being fallible.

REINER: I’m not as modest as I am honest; I know what I’m great at and what I stink at. I’m very good with actors and working a script out structurally, but in terms of the technical aspects, I haven’t come up through film school and directed commercials and videos. With each film I’m learning more about what to do: I tell the cameramen that, and I hope they won’t take advantage of me. Everybody thinks the director is a schmuck, and the fact of the matter is, he is an idiot—any given person working on the film can do their own job better than he can.

BORNS: So you, as the director, are a jack-of-all-trades and the master of none.

REINER: Right, except that I have the ability to see the overall picture, which is really the director’s job.

BORNS: Did you write as a child?

REINER: I wrote poetry when I was young, but nothing of consequence. I think it was like the male version of Sylvia Plath—very depressing, alienated stuff. My father found my poems in the house recently and gave them to me. I was shocked that I’d written those things!

BORNS: It must be strange to grow up in a house filled with comedians and write Sylvia Plath-like poems.

REINER: Yeah, not pretty— wrote about people dying in their own vomit and that kind of stuff…..I don’t know what was going on, but it wasn’t a pleasant sight.

BORNS: Did being a depressed child make you creative?

REINER: I don’t think depression—or any emotional problem-makes you creative. I think people create despite anxiety and depression, not because of it. I think you have to experience pain in order to write something that is full and complete, but I don’t think you have to be in pain in order to create. In fact, it makes it more difficult.

BORNS: It seems that your emergence from pain is coinciding with the emergence of your creativity.

REINER: Yes, and I hope that my best work is way down the road, when I’m feeling a lot better than I’m feeling now.

BORNS: You have a stepdaughter, Tracy, who’s 22. Do you worry that she’ll go through the same trauma as you, having a famous parent?

REINER: She’ll have it really rough, because she’s got Penny and me. She’s a great kid, very smart and beautiful, but I don’t envy what she’ll have to go through.

BORNS: Were you raised with any religion?

REINER: Not really. My parents are both atheists. I was raised in Jewish communities and was bar mitzvahed—I figured maybe I’d get good presents. Little did I know all I’d get was a fountain pen from Mel Brooks. But I didn’t really get drawn to religion. I was culturally raised Jewish and I’m glad of that. My folks hired a teacher to teach me and other neighborhood kids the history of the Jews and where we came from, but it wasn’t religious indoctrination. We also learned a little Yiddish, which I really use a lot…I’m sitting here getting shpilkes from sitting here with you, and I’m getting so much naches from the shpilkes that I could plotz… No, it really was interesting.

BORNS: Until recently, comedy had a much more Jewish bent.

REINER: Yeah. It’s broadened out more, which is nice. The Jews were in the Catskills, then they went into television. Most of the comedy writers were Jewish….Jews are just funny people.

BORNS: Why is that?

REINER: I think you find ways to survive when you’ve been so persecuted for a long time: You can either laugh or you can cry. If you can find a way to laugh, you laugh; otherwise, you’d be killing yourself.

BORNS: What does it feel like to see people watch your movies and enjoy them? Is it one of the greatest feelings in the world?

REINER: No. Let’s not get carried away. Sex is the best thing in the world—that’s number one. Number two, a good meal. Number three, maybe, is that…maybe.

BORNS: How about criticism? You said some people didn’t “get” Spinal Tap—they thought it really was a documentary.

REINER: Most people didn’t get it, but that’s all right. I’m not doing this for everybody. I’m doing it for myself, and I hope other people will appreciate it as well.